Table of Contents

Table of Contents

In 196561ya Ted Nelson imagined a system of interactive, extendable text where words would be freed from the constraints of paper documents. This hypertext would make documents linkable.

Twenty years later, Tim Berners Lee took inspiration from Nelson’s vision, as well as other narratives like Vannevar Bush’s Memex , to create the World Wide Web. Hypertext came to life.

But hypertext was only one small concept amidst a sea of ideas Nelson spent his life developing.

Most were entwined in his grand vision of Project Xanadu The Pattern Language of Project Xanadu

Project Xanadu as a pattern language, rather than a failed software project , a piece of software that at first

glance looks similar to The Web we’re currently on – a way to access and connect shared human

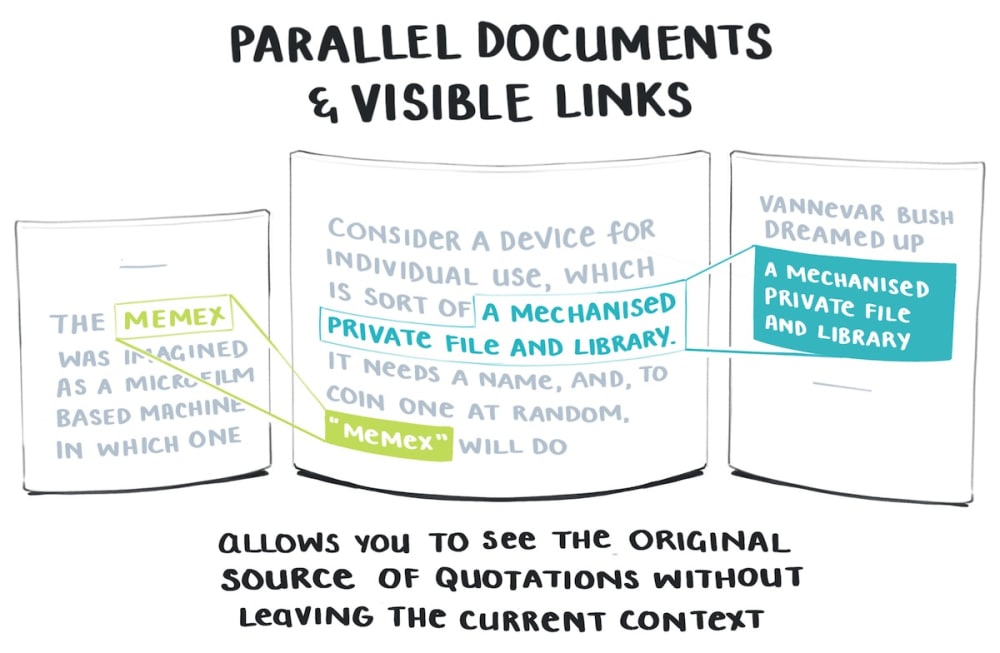

knowledge. But Xanadu was more complex and nuanced. It centered around the principle of “Parallel

Documents, Visibly Linked” – the proposed interface presented documents side-by-side, and

included features like version control and Bi-Directional Links A Short History of Bi-Directional Links

Seventy years ago we dreamed up links that would allow us to create two-way, contextual conversations. Why don't we use them on the web? .

In the historical record, Xanadu is often framed as an alternative to The Web – “the web that could have been” – if it had ever shipped. Unfortunately its complexity led to troubles , and Berners-Lee’s version of hypertext won out.

Despite the fact we’re not currently browsing the Xanadu web, Nelson is still full of provocative, insightful ideas that never quite came to life – some that speak to many of the issues currently plaguing the modern web and are worth revisiting.

Two of the most intruiging are Transclusion and Transcopyright, a pair of concepts that reimagine the way authorship, attribution, copyright, and content monetization might work online.

Transclusion

Transclusion is including one part of a document into another, and maintaing a link between the two. This is different to copying. A copy isn’t inherently linked to it’s original, and can be changed in the duplicate version.

A transclusion is directly linked to the original, and contains the exact same contents. Someone

viewing the transclusion can easily open and view the original document. By doing this,

transclusions create a single source of truth for that element, and a Bi-Directional Link A Short History of Bi-Directional Links

Seventy years ago we dreamed up links that would allow us to create two-way, contextual conversations. Why don't we use them on the web? so you

can navigate between the original source and its instances across the web.

Now, what happens if the original source changes?

The transclusion doesn’t automatically change along with it. If transclusions were direct embeds of the original content, we’d end up with link rot on a whole new scale. Every document would be a sad compilation of 404’s.

You’ve probably’ seen this happen with images – <img> tags where the src element points to an

original source URL are essentially embeds. If the original publisher deletes the photo, your image

dissappears along with it.

Instead, a transclusion is more like a saved version of the original – a cached snapshot of it at a moment in time. You can update that snapshot to a newer version if you want to, but it’s not automatic. Even if the original author deletes it, your transcluded version stays visible.

It works the same way Git does – it’s a version control system that stores the state of a file at a particular point in time.

This idea is powerful in both the possibilities and horrors it could open up. It would allow us to always know where content came from, and see it in its original context. This is a capitvating promise in the age of post-truth informational relativism. We are constantly presented with isolated soundbites, quotes, and tweets that are divorced from the context they were created within.

It would create a more layered and nuanced form of hypertext – something we’re exploring in the

Digital Gardening A Brief History & Ethos of the Digital Garden

A newly revived philosophy for publishing personal knowledge on the web movement. We could build accumulative, conversational exchanges with people on

the level of the word, sentence, and paragraph, not the entire document. Authors could fix typos,

write revisions, and push version updates that propogate across the web the same way we do with

software.

On the flip side, we can also imagine transclusions that once held bible quotes linking back to pages that are now filled with fiery smut. This sort of bad behaviour is inevitable to some degree, but could be minimised through thoughtful design patterns that I’ll touch on later. Cultivating strong social norms, making social reputation visible, and enabling community moderation are all potential tools for it.

Transcopyright

Transcopyright is an extension of transclusion that begins to make this very interesting for attribution, copyright, and monetisation – we begin to see how this might evolve into a sustainable economic system.

If text is able to be endlessly embedded across the web in a way that leads back to a single source and a single publisher, you can theoretically pay that person for every instance of their content showing up on the web.

In this alternate web utopia, readers would pay small amounts for reading content on the web. These micropayments need to be truly micro for this to work. We’re talking fractions of a cent for an article, not the chunky level of $5-10 a month most Patreons and subscription services run at. The majority of that payment would then flow back to the original author.

In this idealised utopia we obviously want to place value on sharing and curation as well as original creation, which means giving a small fraction of the payment to the re-publisher as well.

We should note monetisation of all this content is optional. Some websites would allow their content to be transcluded for free, while others might charge hefty fees for a few sentences. If all goes well, we’d expect the majority of content on the web to be either free or priced at reasonable micro-amounts.

There are a thousand open questions here about the logistics of how this would work. But I find it sad to conclude it’s completely outside the realm of human imagination.

We now have the Web Monetization API up and running, and inevitably the words “blockchain” and “cryptocurrency” might have to be involved here. I’m not brave enough to speculate beyond that.

Designing Speculative Interfaces

What I am comfortable speculating about is how this might look and feel as a user experience. My immediate reaction to this conceptual pair was to try and grasp onto a more grounded version of it.

What would this look like in a real interface? What kind of visual representations and interactions would make this possible? How would I create a transclusion, or pay someone through transcopyright?

Let’s play a design game and think this through.

Here’s a snippet of text I lifted from a recent Wired article, To Mend a Broken Internet, Create Online Parks by Eli Parser:

“There’s a problem of public imagination. Fixing our ability to connect and build healthy communities at scale is arguably an Apollo mission for this generation—a decisive challenge that will determine whether our society progresses or falls back into conspiracy-driven tribalism. We need to summon the creative will worthy of a problem of this urgency and consequence.”

I’ve copied and pasted the text from the article. You can click the link above to view it in context, but you’re going to have to scan the entire page to find the section I copied this from – your browser isn’t going to scroll you to the correct point or highlight the relevant text because it’s not a very smart link 😕.

The original source also has no clue I’ve copied and pasted from it. Nothing on Wired’s article shows how many people have linked to or quoted their article - it currently looks like this:

Which means we have absolutely no visiblity into who else on the web is responding to and building off this piece of writing. If other people have also copied and pasted this snippet of text, adding on their thoughts and ideas, we’ll never know. I’m not saying any of those responses are necessarily good or worth reading. They might all be crap troll comments. But I at least want some visual indication they exist. Unless we really go digging through pages of Google search result for it. Which we’re certainly not going to without good reason.

Transclusion would make this whole scenario quite different. Let’s imagine this again…

As I’m reading this article on Wired, perhaps small indicators show up next to each paragraph showing the number of times each it’s been cited somewhere else on the web.

Below is a simple Figma mockup to demonstrate the idea. Try hovering over the number 8 here and clicking:

An overlay appears with links to those other transclusion instances. If we click on one of those links, we clearly want to see how this snippet of text fits into other contexts. Ideally, they would be links that highlight the relevant text on the destination page and scroll you to the right position.

If we want to offer a more modular browsing experience, we could also have this link modal expand

into the page itself.

Try clicking on the first link in the transclusion list here:

Showing the linked article inline allows us to stay within the current article, but also quickly check what discussions and narratives are happening around it – a feature that might help pop a few of our filter bubbles.

Content Moderation and the Tradgedy of the Comments Section

Many people will react to this prototype with a justified sense of horror.

“If anyone can link to anything on the web and have it show up on the original, everything will devolve into anarchy!”

We can easily imagine transclusions going the way of the public comments section. The 14-year-olds of 4chan might mass-tranclude the introductory paragraph of a New York Times lead story, surrounded by the incendiary lyrics of South Park’s ‘Uncle Fucka’. In fact that would definitely happen.

This system opens up all the gnarly philosophical questions around control, censorship, community moderation, and “free speech” that the web constantly makes tangible and visceral.

What we’re after is a low-friction way for website owners to let other people link to their ideas and creations, offering a rich contextual reading experience for audiences, without letting bad actors monopolise the system.

It goes without saying transclusions need to come with a permissions system. Website owners

might be able to include a single flag in their metadata that turns transclusions off. Something to

the effect of:

<meta name="transclusions" content="disable" />

A subtler approach would be to simply choose not to display transclusion links on their webpage. The

equivalent of transclusions { display: none; } in a css file. In this scenario the transclusions

would still exist, but wouldn’t be as easy to access and read.

Simply reducing it to an on/off switch is a bit of a ham-fisted solution though. It leaves no room for nuance or spectrums of permissioning. Luckily, Ted Nelson baked this consideration into his original ideas.

Transcopyright is of course a copyright system, which means there’s a variety of restrictions and rules about who can use a piece of content across different contexts. As always, IANAL and actual lawyers should feel free to expand on this point and add informed nuance to the argument. I wish you could use transclusions to do so, but Twitter is sadly our best option at the moment.

Coming Soon

Feel free to bug me on Bluesky to finish writing this.