Table of Contents

Table of Contents

People trying to get better at narrative, non-fiction, opinionated writing like essays, blog posts, and conference talks. Most of this advice won’t necessarily apply to fiction writing, academic writing, or technical documentation writing… but it might help.

Opening Essays and Other Pieces of Narrative Writing

Most of the narrative non-fiction The Finest Narrative Non-Fiction Essays

Narrative essays that I consider ideal models of the medium opinion pieces I read online do not grip me in the first sentence. People often start pieces somewhere sensible, but boring. Like the chronological start of a story.

“I first became interested in data structures 17 years ago while pursuing my undergraduate degree. I was reminded of them last week, and decided to write up some notes on what I’ve learned since then.”

The beginning is almost never the most compelling or important part. It’s just the bit you thought of first, based on your subjective chronology.

Or far worse, people begin at The Beginning Of Time. Invoking paleolithic people Paleolithic Nostalgia

Longing for the paleolithic past in the Anthropocene is an overplayed way to convince us your topic is cosmically important.

“For tens of thousands of years, humans have relied on their fingers to do things in the world. Fingers have carved rocks, thrown spears, sewn clothes, and held Doritos. Fingers are essential to our survival. And now, I want to show you how to treat your fingers well by reviewing the top 10 mechanical keyboards on the market in 2024.”

Another bad way to start a piece of writing is with a statement of what you’re going to write about, followed by a definition.

“This post will outline the most common misconceptions in astronomy. Astronomy is the scientific study of celestial objects such as the stars and planets, and misconceptions are falsely held beliefs by a large number of people.”

“Bad” is obviously subjective and contextual here. I find up-front outlines and definitions dull for narrative non-fiction The Finest Narrative Non-Fiction Essays

Narrative essays that I consider ideal models of the medium writing. But they’re standard practice for technical documentation and academic papers. Signposting what you’re going to write about is good, but starting with an exhaustive list of definitions is extremely boring.

To be clear, I make these mistakes too. I am a mediocre opener trying to become a good opener. Opening well isn’t just about snapping up someone’s attention and keeping them reading for a few lines. You can’t write good openings without having good ideas, good arguments, good structure, and good storytelling skills. Everything hangs off that starting point, so it’s worth learning how to nail it.

Tense, Paradoxical, and Problematic Openings

In trying to become a better opener, I’ve collected explicit advice from a few books on writing: Stephen Pinker’s A Sense of Style , John McPhee’s Draft No.4 , and Joseph Williams’ Problems into PROBLEMS . Alongside implicit advice from studying lots of classic essayists like David Foster Wallace , Rebecca Solnit , David Graeber , and Joan Didion . I’m not going to be winning any originality awards for this lot – hard to pick a more cliché array.

If you dislike the way these authors write, it’s best to check out now.

Pinker, McPhee, and Williams each lay out different sets of principles for compelling openings, which I’ll get into in a moment, but for me they all boil down to this: Openings need tension – paradoxes, unanswered questions, and unresolved action.

Good openings propose problems, pose questions, drop you into an unfinished story, or point at fundamental tensions within a topic. Ideally within the first paragraph or two.

“Good writing starts strong. Not with a cliché (“Since the dawn of time”), not with a banality (“Recently, scholars have been increasingly concerned with the questions of…”), but with a contentful observation that provokes curiosity.”

Here’s a good example of this from the opening of David Graeber’s book Bullshit Jobs where he sets up a clear paradox: our technological advances should have led to fewer working hours, but they haven’t. Strange.

“In the year 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that, by century’s end, technology would have advanced sufficiently that countries like Great Britain or the United States would have achieved a 15-hour work week. There’s every reason to believe he was right. In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. And yet it didn’t happen. Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more.”

Here’s another one from David Foster Wallace that asks a series of rhetorical questions to which the presumed answers is “of course not!” And also, “how in the world is something as dull as lexicography filled with drama?” An unexpected contrast.

“Did you know that probing the seamy underbelly of U.S. lexicography reveals ideological strife and controversy and intrigue and nastiness and fervor on a nearly hanging-chad scale? For instance, did you know that some modern dictionaries are notoriously liberal and others notoriously conservative, and that certain conservative dictionaries were actually conceived and designed as corrective responses to the “corruption” and “permissiveness” of certain liberal dictionaries?”

I’m certainly not against a slightly slower narrative opening that sets the scene before making the puzzle or conundrum clear, but you can’t take too long to get there. Here’s a more drawn out one from Rebecca Solnit that gives you some scenic details before pointing out the curiosity; priviledged tech workers in San Fransisco fail to understand why locals hate them.

“The young woman at the blockade was worried about the banner the Oaklanders brought, she told me, because she and her co-organisers had tried to be careful about messaging. But the words FUCK OFF GOOGLE in giant letters on a purple sheet held up in front of a blockaded Google bus gladdened the hearts of other San Franciscans. That morning – it was Tuesday, 21 January – about fifty locals were also holding up a Facebook bus: a gleaming luxury coach transporting Facebook employees down the peninsula to Silicon Valley.

One protester shook a sign on a stick in front of the Google bus; a young Google employee decided to dance with it, as though we were all at the same party. We weren’t. One of the curious things about the crisis in San Francisco – precipitated by a huge influx of well-paid tech workers driving up housing costs and causing evictions, gentrification and cultural change – is that they seem unable to understand why many locals don’t love them.”

Putting the word FUCK in all caps in your opening is a valid way to get people’s attention, but you’ll need to back it up with a good story. Unlike the dozens of Mark Manson-ites who have cheaply used the sacred word to sell crappy self-help books like Unf✶ck Yourself, Grow the F✶ck Up, and The F✶ck It Diet.

Let’s have another Rebecca Solnit one because she’s so damn good at this. Here’s an opening for a piece on how we shouldn’t think about fixing climate climate as a swift, immediate task, but instead a slow, gradual, persistent challenge.

“Someone at the dinner table wanted to know what everyone’s turning point on climate was, which is to say she wanted us to tell a story with a pivotal moment. She wanted sudden; all I had was slow, the story of a journey with many steps, gradual shifts, accumulating knowledge, concern, and commitment. A lot had happened but it had happened in many increments over a few decades, not via one transformative anything.

People love stories of turning points, wake-up calls, sudden conversions, breakthroughs, the stuff about changes that happen in a flash. Movies love them as love at first sight, dramatic speeches that change everything, trouble that can be terminated by shooting one bad guy, and other easy fixes and definitive victories. Old-school radicals love them as the kind of revolution that they imagine will change everything suddenly, even though a change of regime isn’t a change of culture and consciousness.”

Finding Tension, Paradoxes and Problems

Fiction writers have it easy. When they hear that stories should start “in the middle of the action,” they can make it so. They can open with the main character’s feet dangling off the edge of a cliff with a fiery pit below (or something less heavy-handed and melodramatic).

Creating tension in non-fiction work is trickier because your story is (hopefully) constrained by reality. You are not at liberty to invent suspicious murders, salacious extramarital affairs, or newly-discovered-magical-powers to create tension and mystery. You have to deal with the plain, unexotic facts of the world.

Your challenge is finding the compelling problem in your topic, and clearly presenting it up front. That problem might be deeply buried under a bunch of boring facts and informational details. It might be hard to figure out what it is, and hard to describe once you’ve found it.

Your job becomes much harder if you pick topics with no tension, problems, or puzzles within them. To paraphrase Williams, it is more of a failure to pose an uninteresting problem, than to poorly articulate an interesting one.

Your interest in the topic is your best directional clue for finding the tension or interesting paradox. Your urge to write about the thing hopefully comes from a place of curiosity. You have unanswered questions about it. It feels important or consequential for unexplained reasons. You think you’ve seen things in it other people haven’t. Pay attention to that interest.

Joseph Williams has some good advice for finding and clearly stating these paradoxes and problems. In Part I of “ Problems into PROBLEMS ”, he lays out a slightly formulaic, but useful way of thinking about problems.

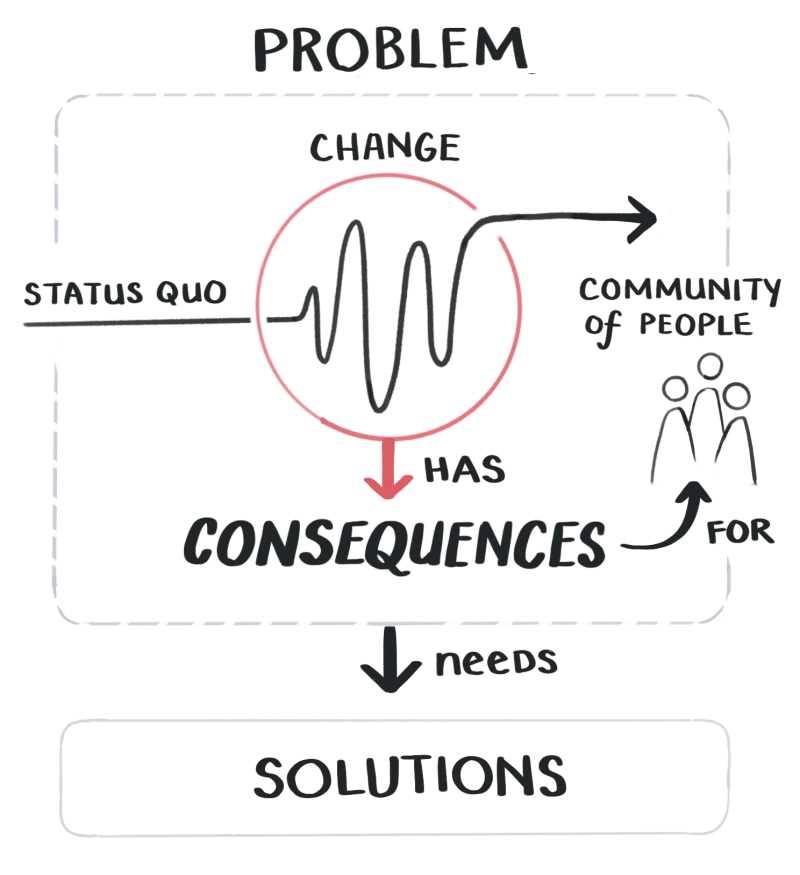

Problems are a destabilising condition that has a cost for a community of readers that needs a solution. Destabilising condition is just a fancy word for “change” here – a change in the status quo. Put another way, a problem is an expected turn of events, that has undesireable consequences, for an audience who will care about it, that we want to explore solutions to.

The change here could be a new technological or cultural development like carbon sequestration, web components, critical race theory, or crowd funding. Or it could be a single event like someone making an influential speech or stepping down as a leader.

The change doesn’t have to be bad and the consequences aren’t necessarily negative. It’s simply that the state of the world has shifted, and there are knock-on effects that your community (a.k.a. your readers or assumed audience Assumed Audiences

Naming your invisible audiences to free yourself from unspoken obligations ) should care about and explore solutions or responses to. These are changes they need to react to in some way, even if we don’t yet have a clear solution.

Here’s an examples from Williams:

Recently, the thinning of the ozone layer has allowed sunlight to reach

the earth unfiltered. CHANGE

As a result, we are going to have more cancer and higher medical costs. CONSEQUENCES for a COMMUNITY

We can avoid these consequences only if we ban chemicals that degrade ozone. SOLUTION / RESPONSE

It’s a good exercise to read openings in essays or news articles and try to identify these. They don’t always appear in order, and they’re usually spread over the first few paragraphs. Here’s another example from a New York Times opinion piece:

Aadhaar, India’s grand program to provide a unique 12-digit identification number to each of its 1.3 billion residents, appears to be collapsing under its own ambitions. CHANGE

So far, [it] seems to have helped neither with welfare nor against corruption, all the while creating new problems, including by exposing people’s personal data to theft or predation by the private sector. CONSEQUENCES for a COMMUNITY

Given the many ways in which the system is broken, at the very least it should be made voluntary again, and the data of anyone who opts out should be destroyed. SOLUTION / RESPONSE

These examples are clearly a bit simplified and boring. Williams is speaking to a community of academic writers in his book. They’re trying to present scientific and research problems in plain, objective language, which isn’t necessarily what we want to do with narrative writing like blogging or personal essays.

We have a little more liberty to put interesting padding around the change, consequences, and solution, such as telling an opening anecdote, or drawing readers in with characters, rich details, and sensory descriptions.

Consequential Problems

Our first idea of the “problem” is often not consequential enough and we have to dig deeper to find more compelling underlying problems. Williams suggests we try to state our problem and then ask a series of so what?’s to get at the underlying problem. Let’s try it.

Starting problem

Language models are able to write text that looks just like a human wrote it.

So what?

We won’t be able to tell whether a language model or a human wrote something. Language models can write much faster than humans, and the volume of text they generate will overtake the volume humans can make.

So what?

Language models don’t have accurate knowledge of the world and often hallucinate. Our already brittle and broken systems for vetting and diseminating true statements about the world will become weaker.

So what?

Misinformation and disinformation will spread even further and faster, fracturing our shared reality as a society. Shared truths and common ground will die, threatening democratic governance systems and societal cohesion.

Whether I can support that final problem with solid evidence and argue for it convincingly is my job for the rest of the writing piece, but at least I’ve begun with a compelling problem.

For your writing to be worth reading, you need to be exploring something of consequence for someone. You have to have some kind of problem that matters. Even if it’s a personal problem like a medical issue, career challenge, or difficult technical bug, you’re hopefully writing about it to help others encountering a similar situation.

Time, Place, Character, and Dramatic Action

Once you know you have a consequential problem for a community and some sense of a solution, you get to play with narrative details. This is the fun storytelling part.

There’s an opening style I’ve seen a lot in publications like The New Yorker and The Atlantic that effectively places us in a real time and place, with real characters we want to follow along with. It goes like this:

On {date} in {place}, {character} did {strange / compelling / dramatic thing}.

The strange, compelling, or dramatic thing has to be extreme enough that we now want to know much more about the character and how they came to be doing this thing in this time and place.

Here are some good examples of it:

“On 23 May 2014, Elliot Rodger, a 22-year-old college dropout, became the world’s most famous ‘incel’ – involuntary celibate. The term can, in theory, be applied to both men and women, but in practice it picks out not sexless men in general, but a certain kind of sexless man: the kind who is convinced he is owed sex, and is enraged by the women who deprive him of it. Rodger stabbed to death his two housemates, Weihan Wang and Cheng Hong, and a friend, George Chen, as they entered his apartment on Seville Road in Isla Vista, California.”

“On the morning of August 26, 2021, a sweaty young American diplomat named Sam Aronson stood in body armor near the end of a dusty service road outside the Kabul airport, contemplating the end of his life or his career. Thirty-one and recently married, 5 foot 10 without his combat helmet, Sam surveyed the scene at the intersection near the airport’s northwest corner, where the unnamed service road met a busy thoroughfare called Tajikan Road. Infected blisters oozed in his socks.”

It’s a little formulaic, but it works well. It’s pulling us into the scene with rich sensory descriptions and specific details that point at the core problems or tensions the writing will explore.

Here’s a more creative way of dropping the reader into the rich details of a scene without relying the time / place / character / action framework:

“I have now seen sucrose beaches and water a very bright blue. I have seen an all-red leisure suit with flared lapels. I have smelled suntan lotion spread over 2,100 pounds of hot flesh. I have been addressed as “Mon” in three different nations. I have seen 500 upscale Americans dance the Electric Slide. I have seen sunsets that looked computer-enhanced. I have (very briefly) joined a conga line. I have seen a lot of really big white ships. I have seen schools of little fish with fins that glow. I have seen and smelled all 145 cats inside the Ernest Hemingway residence in Key West, Florida.”

David Foster Wallace is very good at rhythmic lists like this. It made me love lists.

Starting in the Middle

I said before the chronological beginning is rarely the most compelling or important part of a story. If your story has a narrative over time (and almost all do, even if it’s about why you like a hot new JavaScript framework ), you might need to start telling it in the middle, then jump back to the beginning later on to fill readers in.

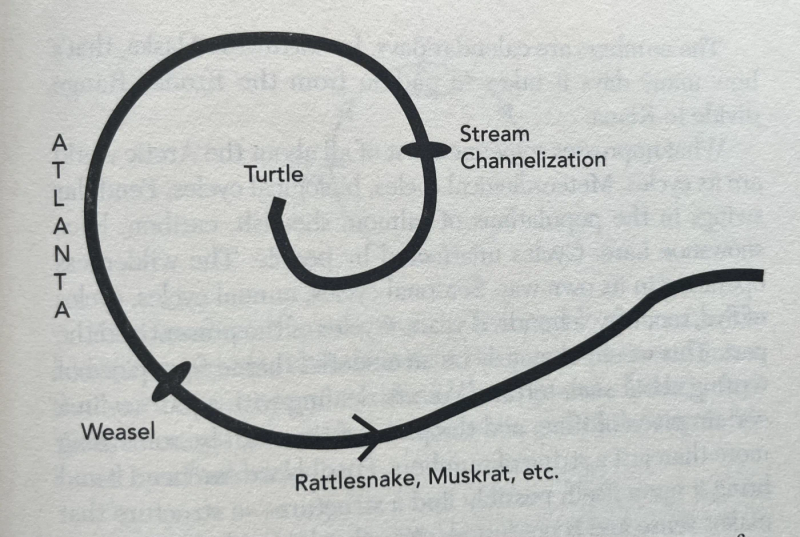

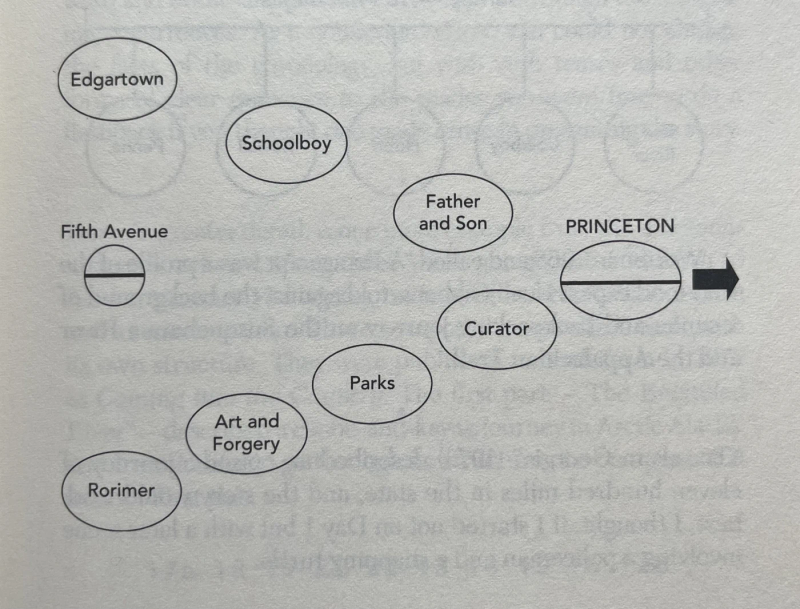

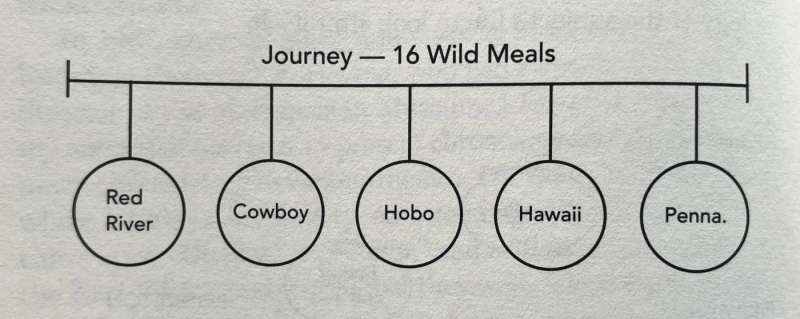

John McPhee is the master of structuring narrative writing. If you’re unfamiliar with his work, start with his essays , or consider his Pulitzer Prize winning tome on the geological history of the United States. Anyway, the guy knows how to make rocks consistently fascinating for 660 pages.

In his writing guide Draft No. 4 , the chapter on structure is filled with wonderful diagrams like this:

These are the shapes of stories. When McPhee writes, after first immersing himself in his raw material (field notes, interview transcripts, official documents) for weeks, he then draws a structure for the work. The structure lays out the major themes and scenes he’ll work through, in the order that will make them most compelling and coherent.

Developing a structure requires navigating the tension between chronology and theme. Chronology is what we default to, but themes that repeatedly appear want to pull themselves together into a single place. The themes that really matter should be in your opening. Even if the moment that best defines them happens right before the end of the timeline.

Opening Conference Talks

Most of the rules for opening pieces of writing apply to opening conference talks, but they require more traditional signposting of what you’re going to cover.

Live conference talk audiences are trapped in a way reading audiences are not. They can’t close the tab on your presentation. So I try to quickly give them more explanation of where my story is going and why it’s worth their valuable attention.

I’ve been trapped in plenty of audiences where we’re 5 minutes into an anecdote about the speaker’s childhood, and the whole room is desperately trying to figure out what The Point is. This is cruel and frustrating.

You should make The Point clear as soon as possible. Somewhere in the first minute I make sure to say:

- This talk is about X: a compelling problem with consequences for this audience, for which I have some suggested solutions

- We’re going to talk about A, B, C, and D, in that order

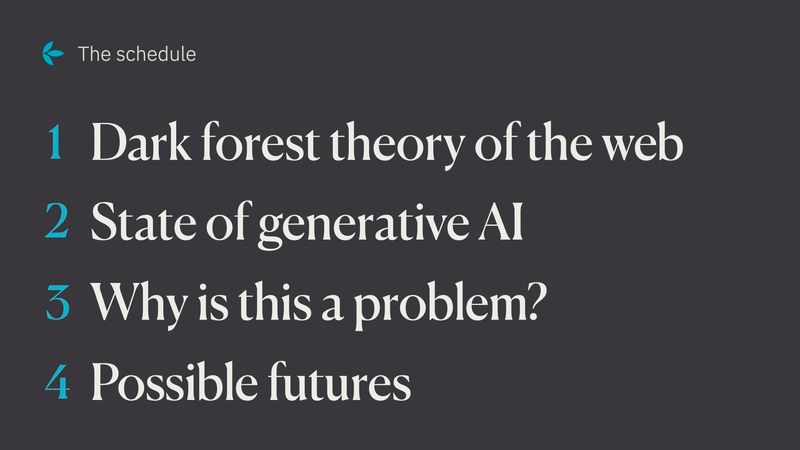

Here are two of the opening slides from my Expanding Dark Forest and Generative AI The Expanding Dark Forest and Generative AI

An exploration of the problems and possible futures of flooding the web with generative AI content talk:

This outline isn’t especially detailed, but now the audience has a map of where we’re going. They understand the structure of my argument and can tell what I am and am not going to cover.

Opening Jam Jars

To open a jam jar, you should run it under a very hot tap. Resort to the kettle if your tap is lukewarm. The heat makes the metal lid expand faster than the glass, which creates space between the lid and the jar.

Then place a tea towel over lid, firmly grip the top, and twist. Repeat until you run out of grip strength, and then recruit someone else to help. They will effortlessly pop it off for you. Do not skip the last step.

Some people advise banging the jar lid on the counter-top to loosen it, but I once smashed a pickle jar this way, showering myself in vingear, soggy dill, and tiny glass shards. I now believe it’s not worth the risk.