Slides, transcript, and video from my talk on how language models and generative AI could lead us to an epistemic meltdown on the web.

This is an expansion of my essay The Dark Forest and Generative AI The Dark Forest and Generative AI

Proving you're a human on a web flooded with generative AI content published in January 20233ya .

First presented at Causal Islands in Toronto, April 2023. Updated for Web Directions in Sydney, Australia in October 2023, FFConf in Brighton in November 2023, Beyond Tellerrand in Dusseldorf in May 2024, and UX Brighton in November 2024.

Causal Islands Recording – April 2023

Beyond Tellerrand Recording – May 2024

References in order of appearance

The Dark Forest Theory of the Internet

Yancey StriklerThe Extended Internet Universe

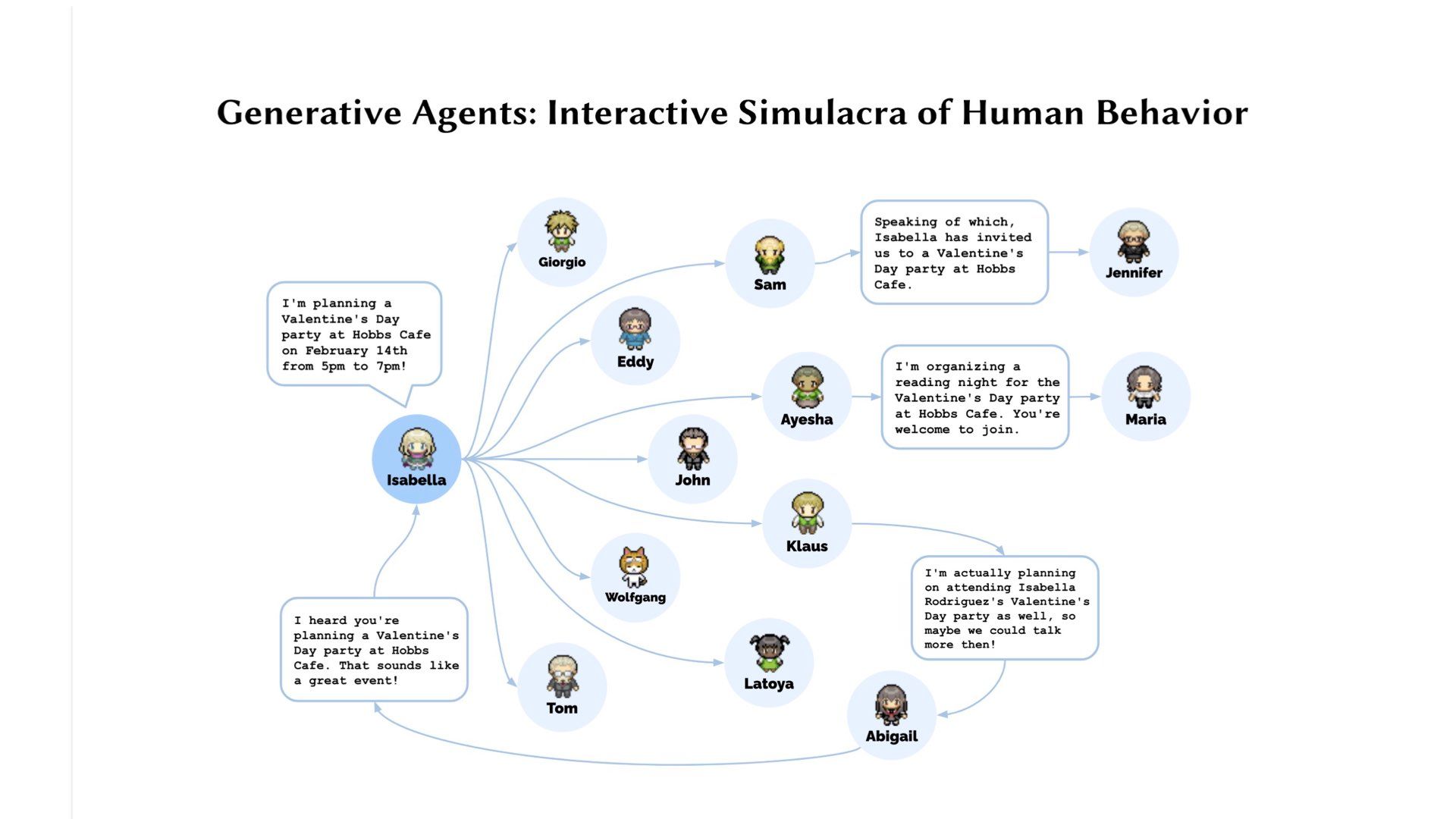

Venkat RaoGenerative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior

Joon Sung Park, et al.Al is being used to generate whole spam sites

James Vincent for The VergeA New Frontier for Travel Scammers: A.I.-Generated Guidebooks

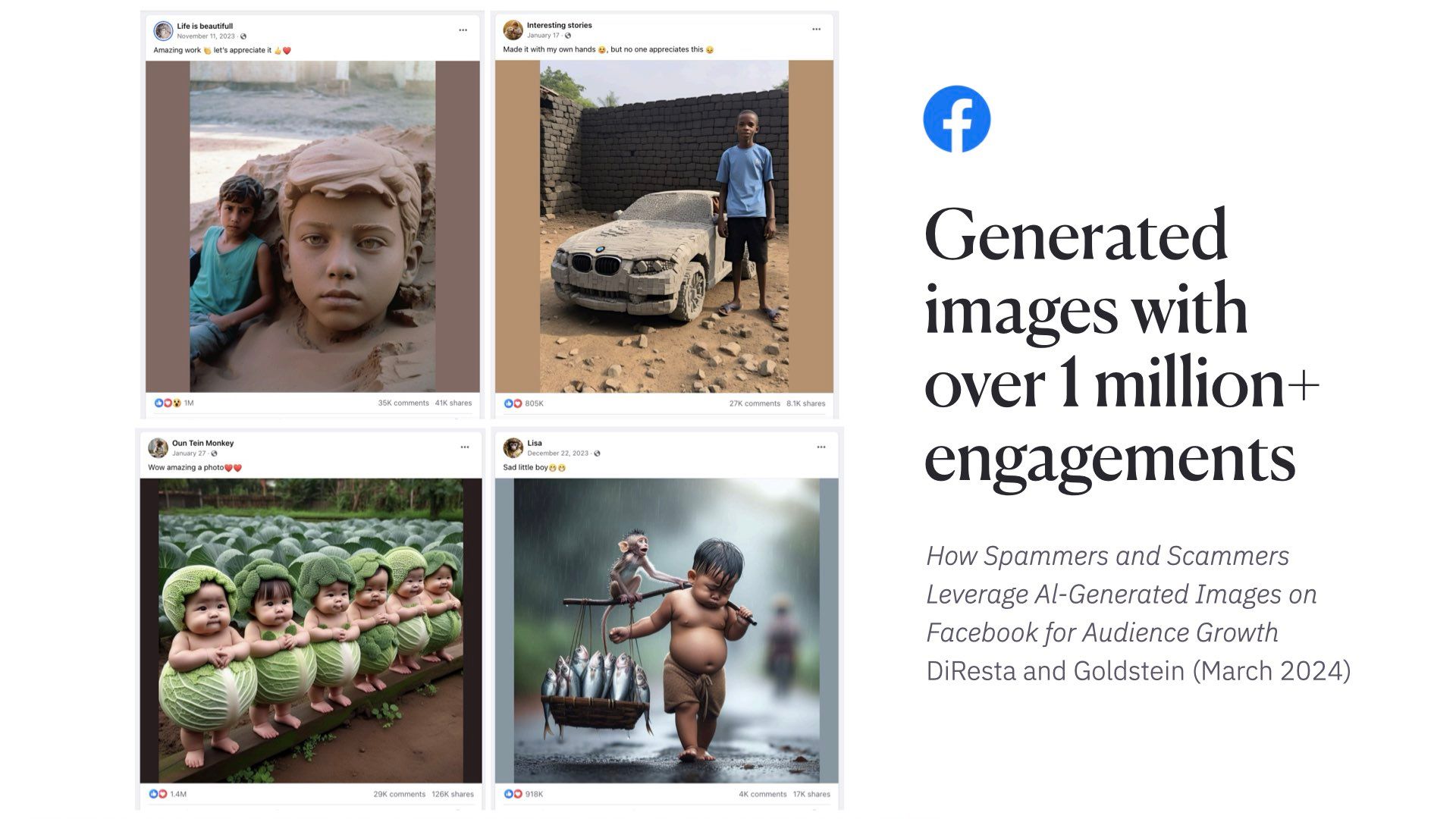

Seth Kugels and Stephen Hiltner for The New York TimesHow Spammers and Scammers Leverage AI-Generated Images on Facebook for Audience Growth

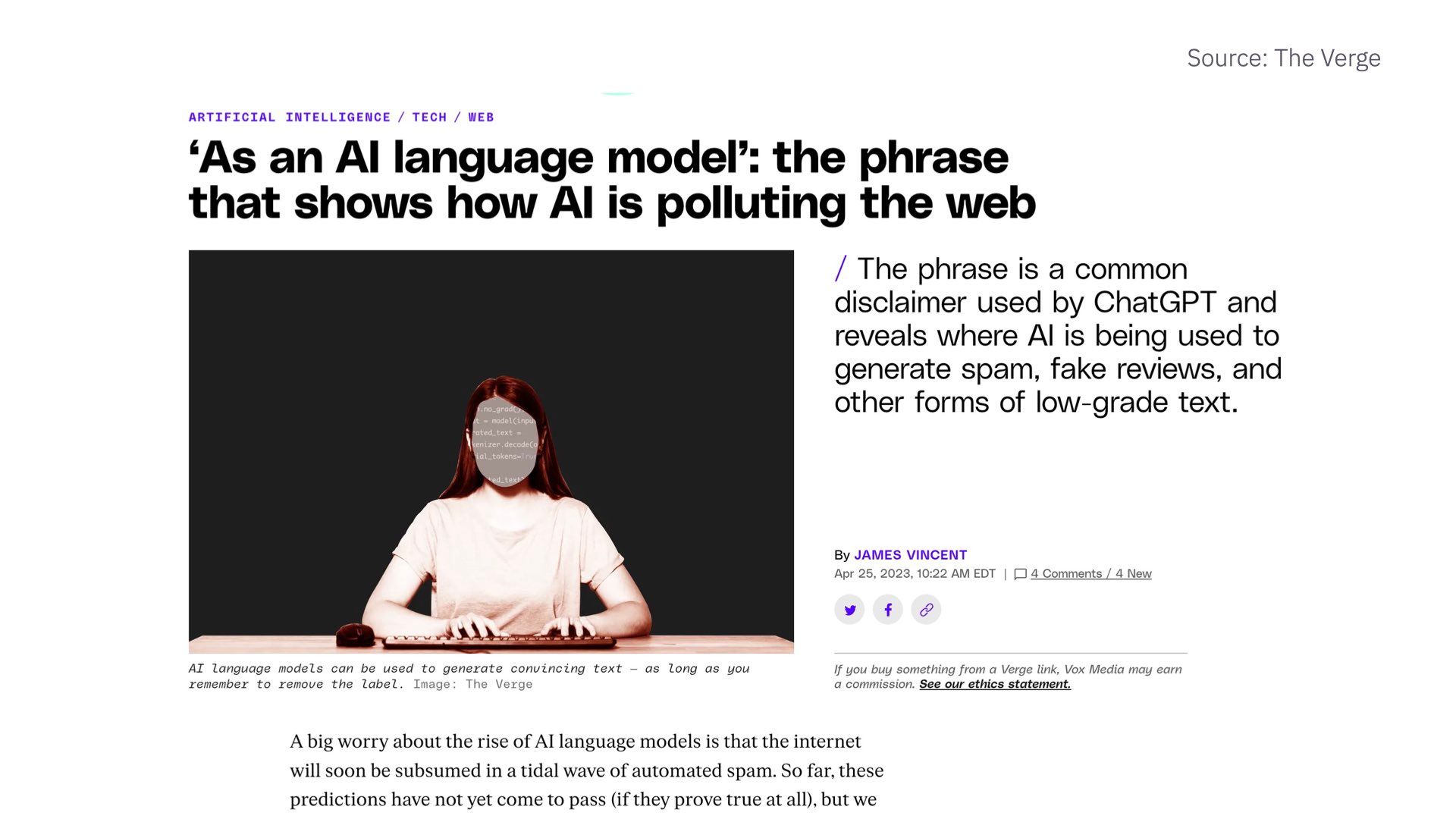

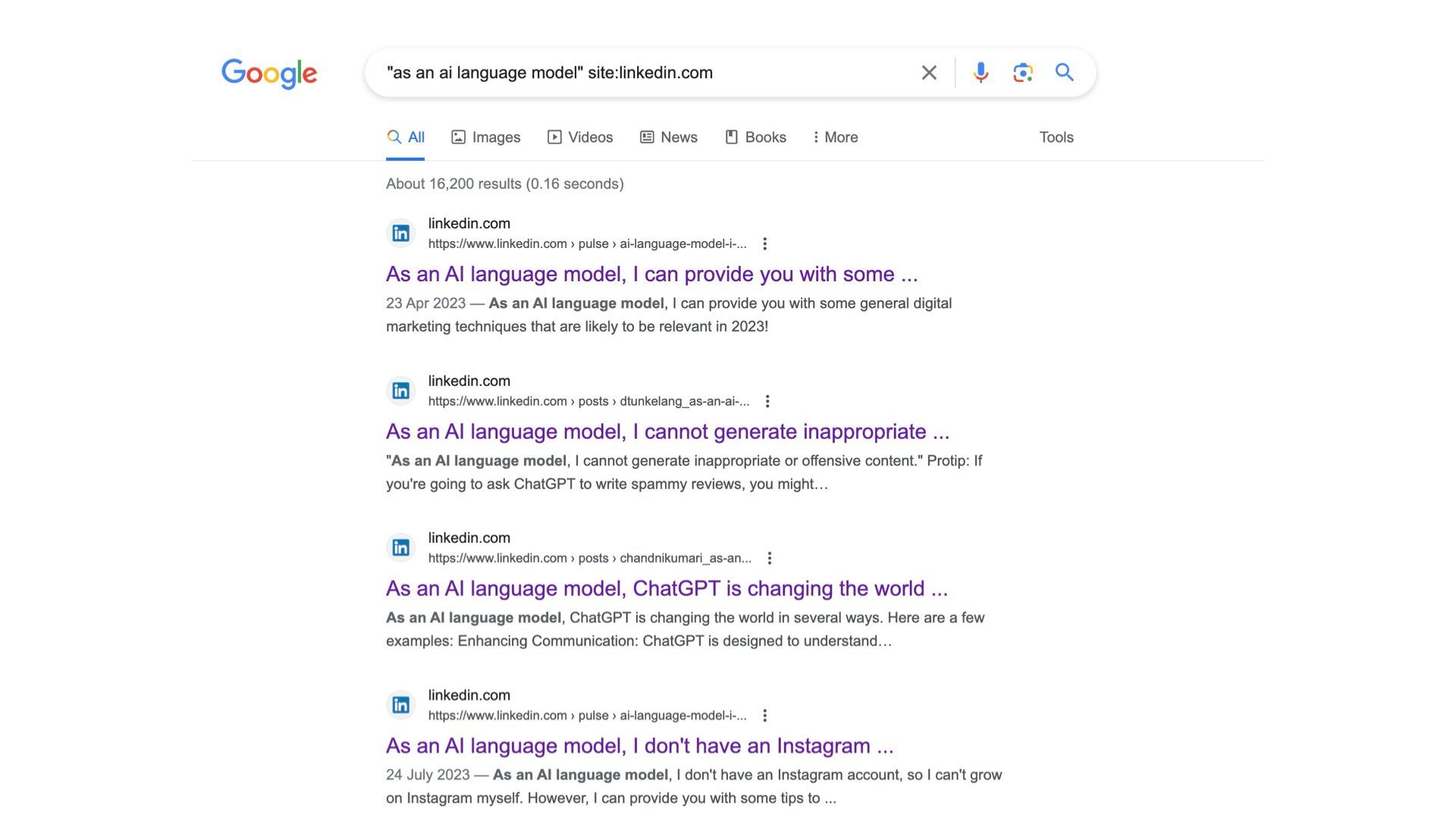

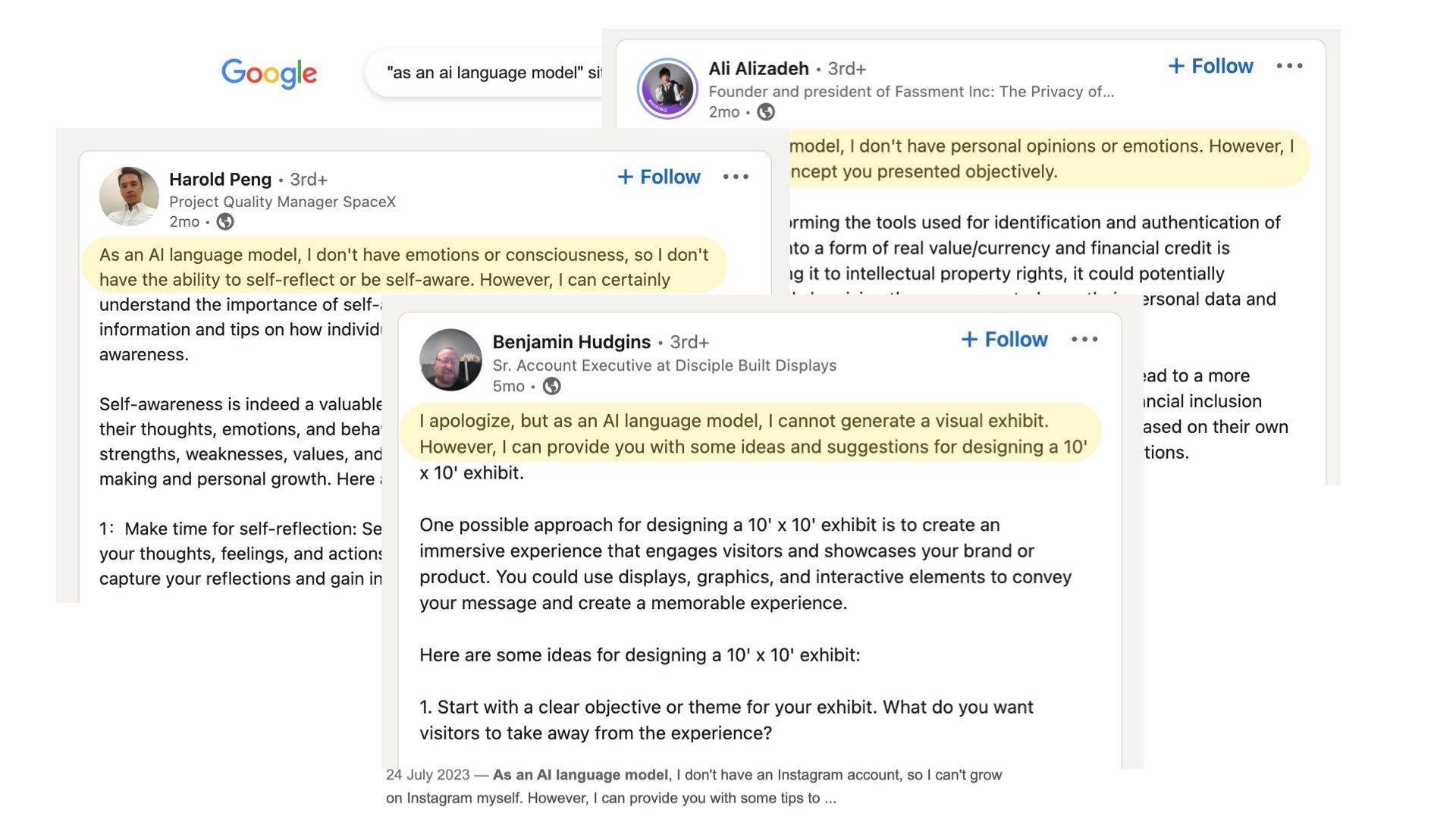

Renee DiResta & Josh A. Goldstein'As an Al language model': the phrase that shows how Al is polluting the web

James Vincent for The VergeComparing scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT to original abstracts using an artificial intelligence output detector, plagiarism detector, and blinded human reviewers

Catherine Gao, et al.Cyborgism

Nicholas Kees and Janus on LessWrongSlides and Transcript

This is going to be about writing on the web, trust, and human relationships (small fish)

And inevitably, AI. Sorry.

A small footnote: this talk up to date as of about 2 weeks ago which means everything I say about the current state of AI is probably completely irrelevant by now.

I have essentially gathered some thoughts that relate to a moment in time that has just whooshed past us.

First, some context. I’m Maggie and I want to lay out all my biases up front.

I’m a designer at an AI research lab called Elicit . My job involves creating tools that use language models to augment and expand human reasoning.

In practice, these tools are primarily aimed at academics and large organizations such as governments and non-profits, helping them to understand scientific literature and make decisions.

Secondly, I’m what we call “very online”. I live on Twitter and write a lot online. I hang out with people who do the same, and we write blog posts and essays to each other while researching. As if we’re 18th-century men of letters. This has led to lots of friends and collaborators and wonderful jobs.

Being a sincere human on the web has been an overwhelmingly positive experience for me, and I want others to have that same experience.

Lastly, before I joined tech, I studied cultural anthropology. I like to think this gives me some useful perspectives, frameworks, and tools to think about culture and social behaviour on the web.

I’ll first discuss the dark forest theory of the web, then talk about the state of generative AI.

We’ll then consider if we have a problem here. I’ll lay out hypothetical problems and examine if they’re valid.

Then we’ll cover possible futures and how to deal with those hypothetical problems.

To explain the dark forest theory of the web, I first need to explain the dark forest theory of the universe. This theory attempts to explain why we haven’t yet discovered intelligent life in the universe.

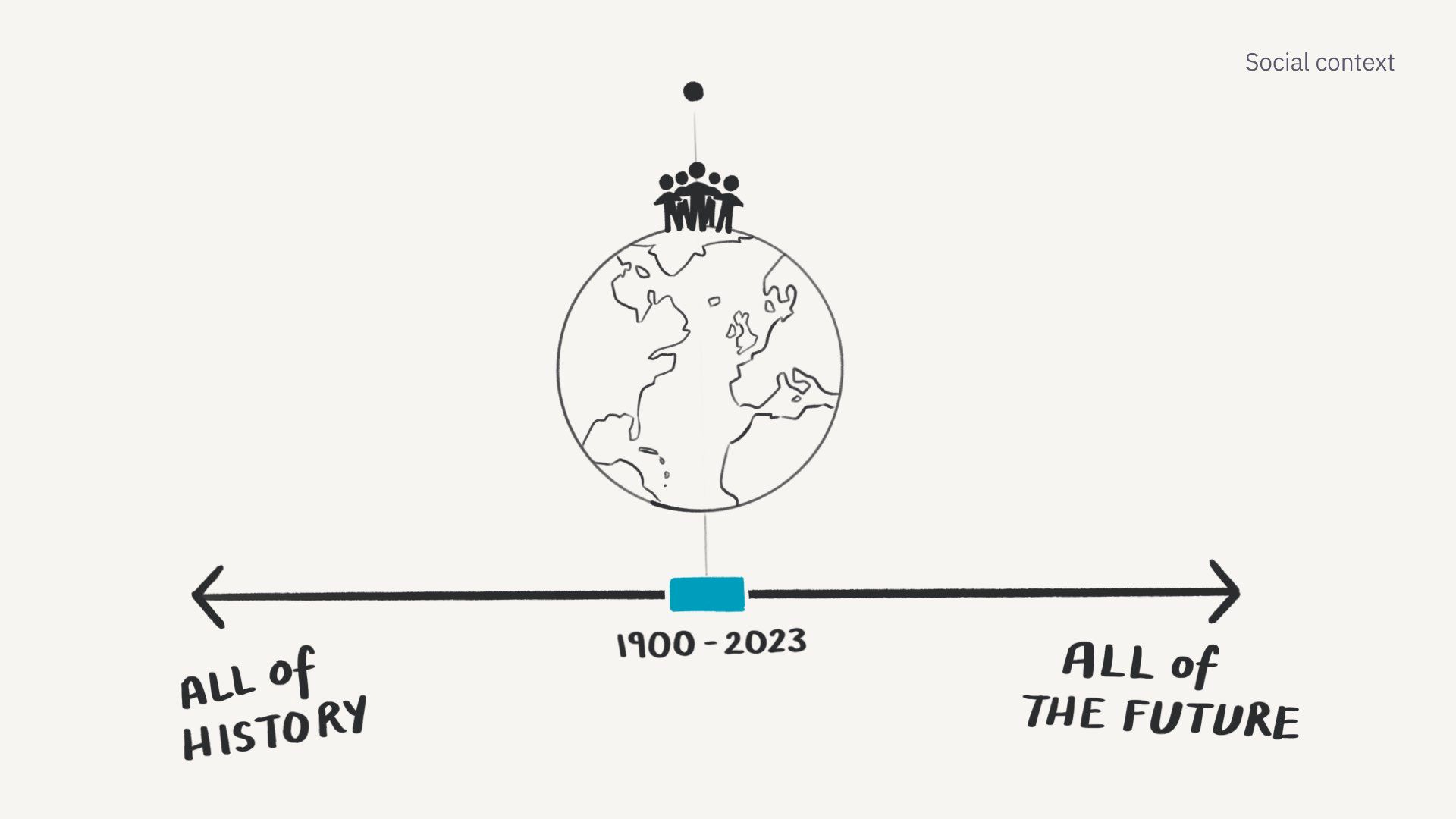

Here we are - the pale blue dot

As the only known intelligent life in the universe, we’ve been beaming out messages for 60 years in an attempt to find others.

But we haven’t heard anything back yet.

Dark forest theory suggests that the universe is like a dark forest at night - a place that appears quiet and lifeless because if you make noise…

…the predators will come eat you.

This theory proposes that all other intelligent civilizations were either killed or learned to shut up. We don’t yet know which category we fall into.

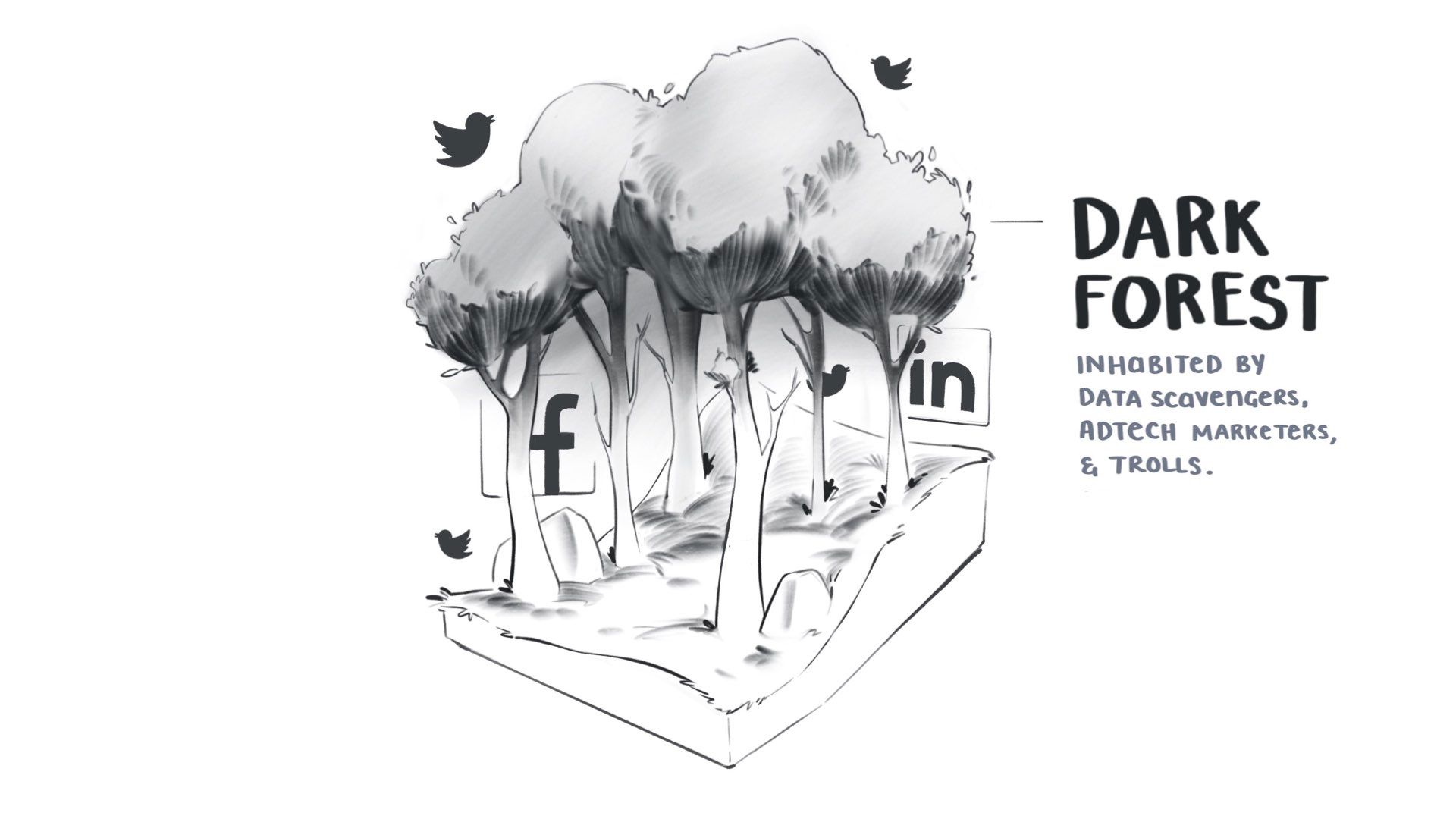

The web version builds off that concept

This is a theory proposed by Yancey Striker in 2019 in the article The Dark Forest Theory of the Internet

Yancey describes some trends and shifts around what it feels like to be in the public spaces of the web.

Yancey pointed out two main “vibes”. First, the web can often feel lifeless, automated, and devoid of humans.

Here we are on the web

And we’re naively writing a bunch of sincere and authentic accounts of our lives and thoughts and experiences. Trying to find other intelligent people who share our beliefs and interests

But feels like we’re surrounded by content that doesn’t feel authentic and human. Lots of this content is authored by bots, marketing automation, and growth hackers pumping out generic clickbait with ulterior motives.

We have all seen this stuff.

Low-quality listicles…

…productivity rubbish…

…insincere templated crap…

…growth hacking advice…

…banal motivational quotes…

…and dramatic clickbait.

This stuff may as well be automated. It’s rarely trying to communicate sincere and original thoughts and ideas to other humans. Mostly trying to get you to click and rack up views.

The overwhelming flood of this low-quality content makes us retreat away from public spaces of the web. It’s too costly to spend our time and energy wading through it.

The second vibe of the dark forest web is lots of unnecessarily antagonistic behaviour, at scale.

When we put out signals trying to connect with other humans, we risk becoming a target.

Specifically, the Twitter mob might come to eat us.

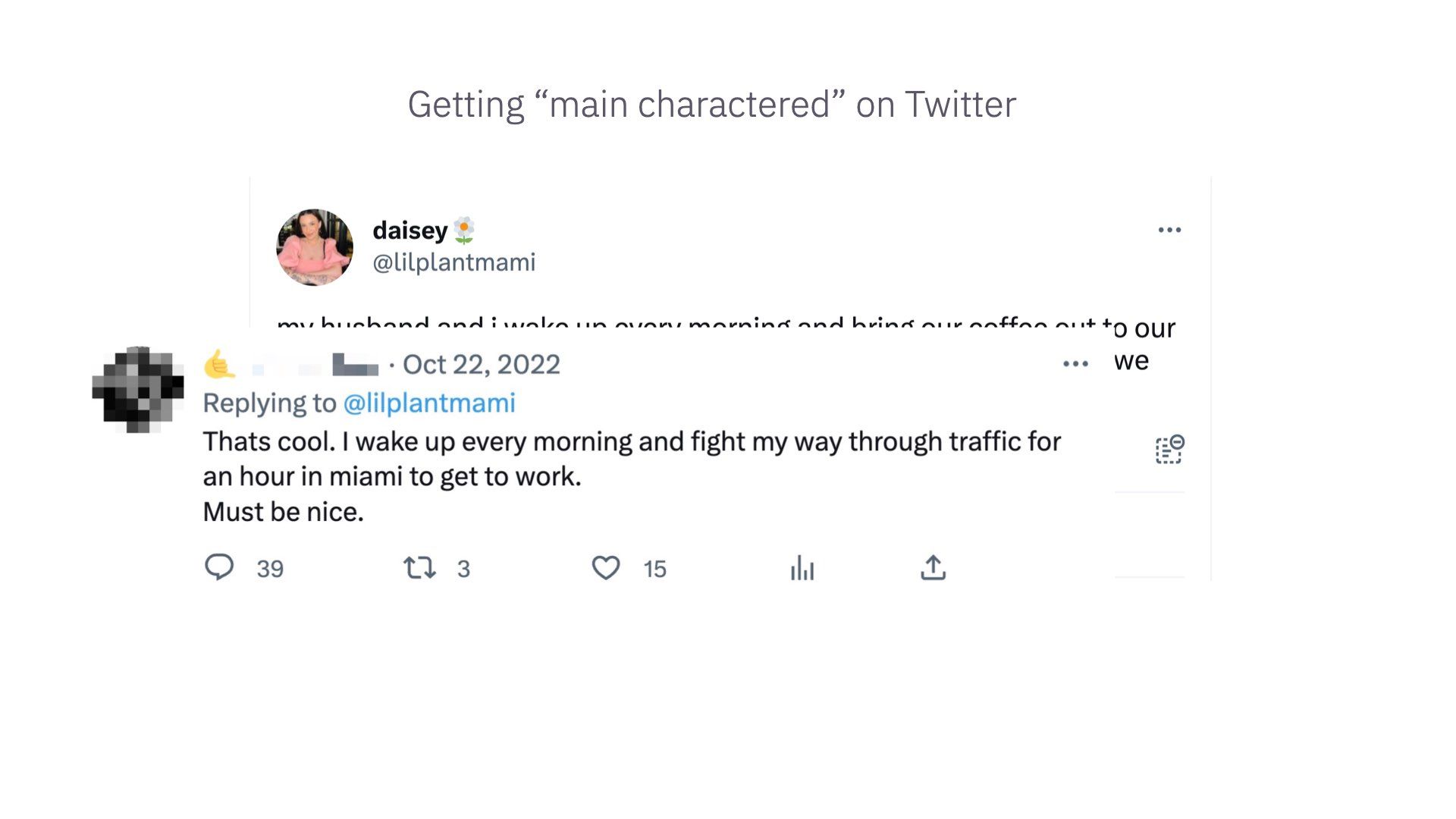

There’s a term on Twitter called getting “main charactered”.

Every day there is one main character on Twitter and your goal is to not be that character. They get piled on by everyone for saying the wrong thing. Sometimes they deserve it, but it’s often quite arbitrary. I’ve had close friends get main charactered for frankly very banal and minor things

A good example of this is garden lady from October.

Some of you may have seen this. This woman tweeted this lovely, sweet message about loving her husband and spending hours every morning talking to him in the garden over coffee.

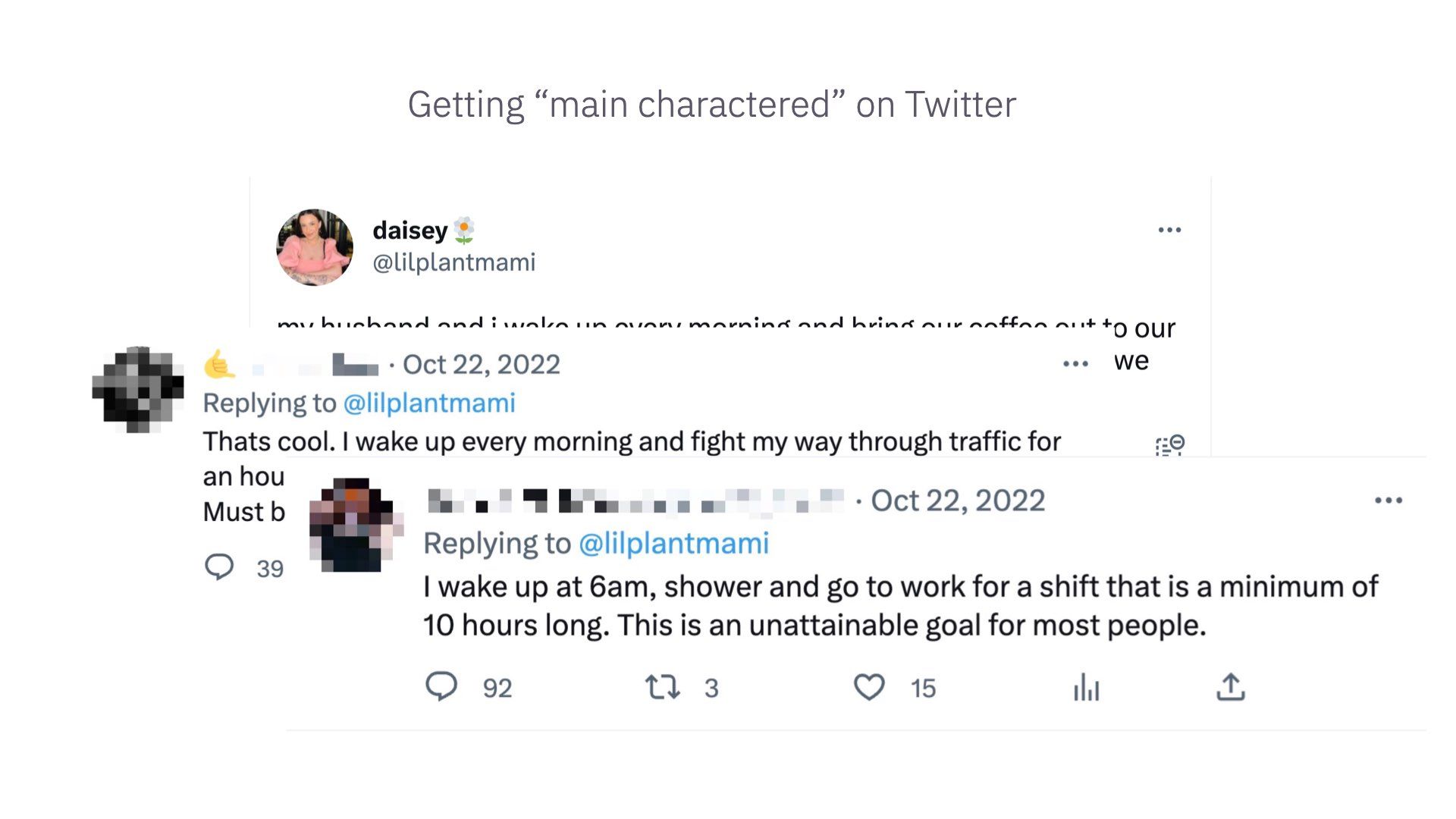

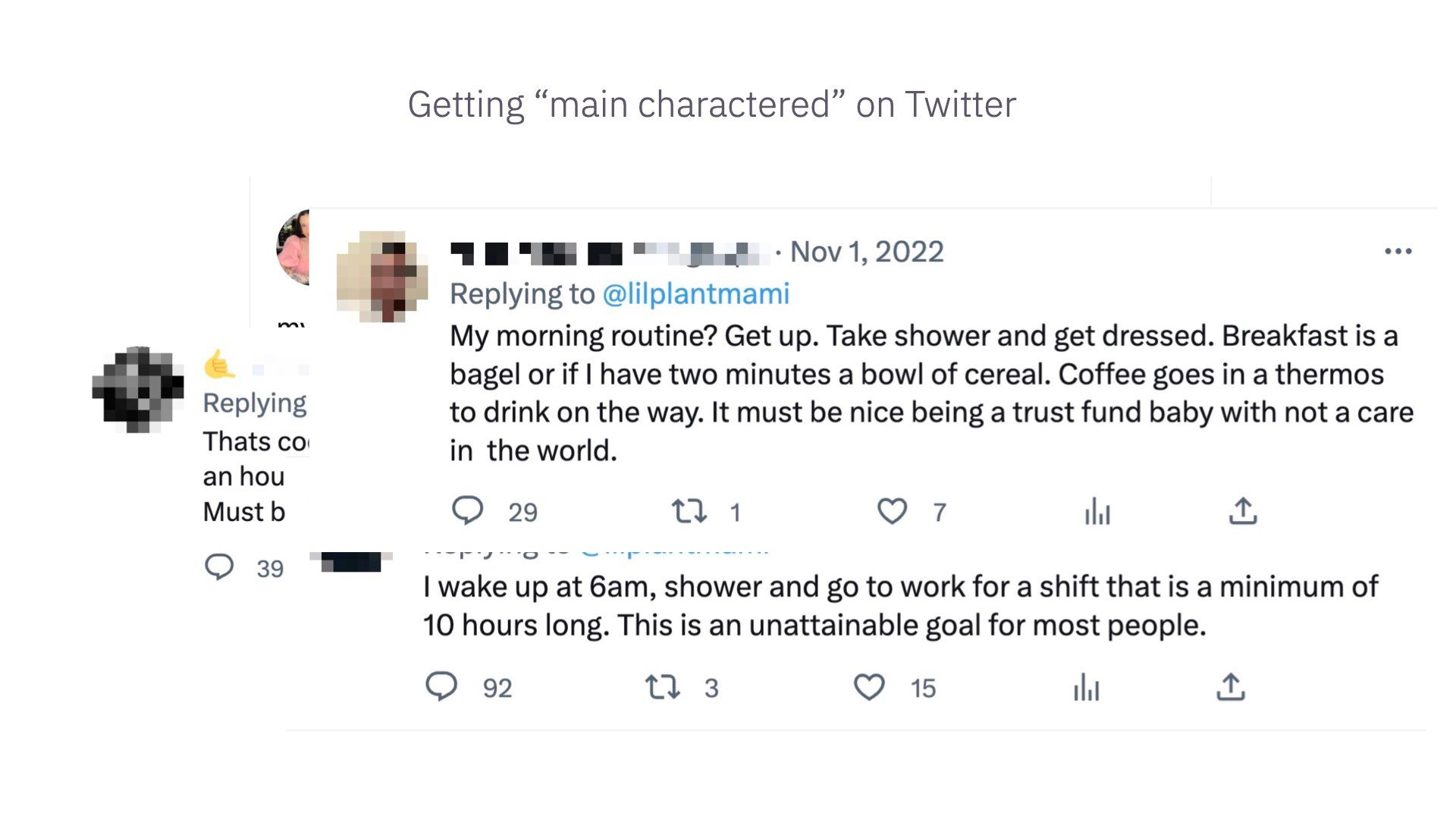

The replies were priceless

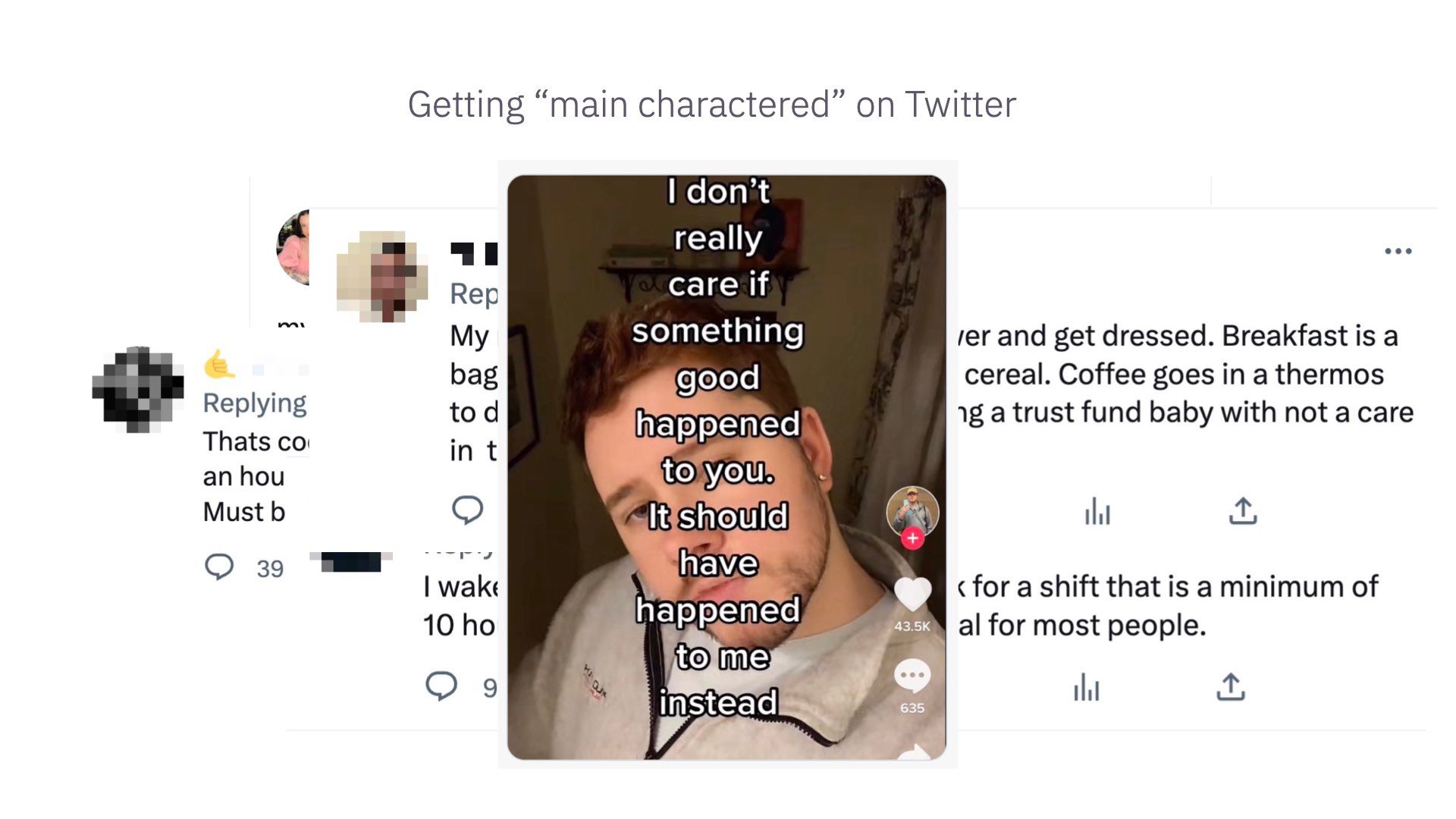

TikTok captured this vibe well – “I don’t really care if something good happened to you. It should have happened to me instead.”

In his book “So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed,” Jon Ronson explores how cancelling and publicly shaming others has become a common practice on social media.

This phenomenon has real material consequences for people, causing them to lose their jobs, become alienated from their communities, and suffer emotional trauma.

Many people choose not to engage on the public web because it’s become a sincerely dangerous place to express your true thoughts.

It’s difficult to find people who are being sincere, seeking coherence, and building collective knowledge in public.

While I understand that not everyone wants to engage in these activities on the web all the time, some people just want to dance on TikTok, and that’s fine!

However, I’m interested in enabling productive discourse and community building on at least some parts of the web. I imagine that others here feel the same way.

Rather than being a primarily threatening and inhuman place where nothing is taken in good faith.

So, how do we cope with this?

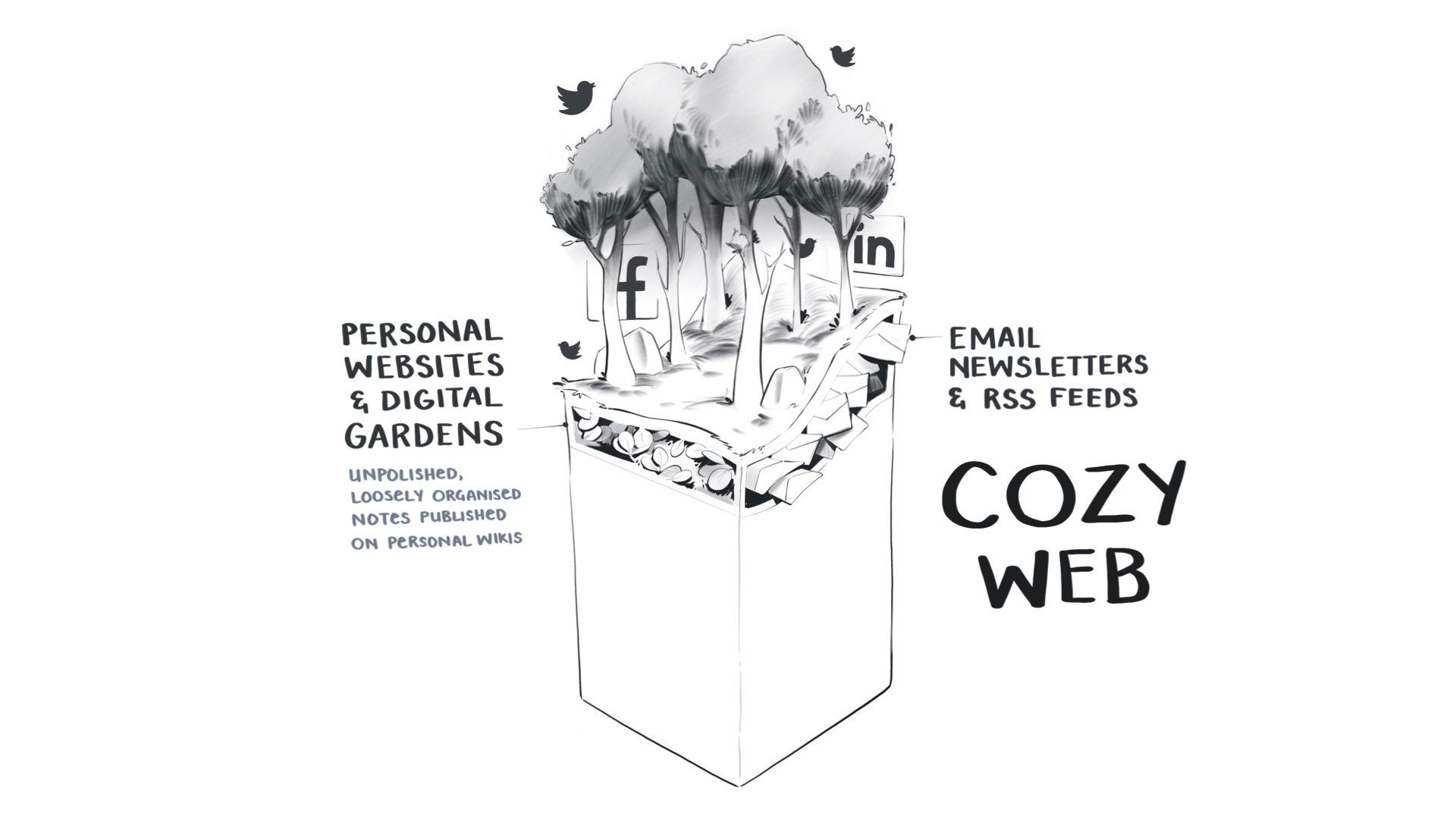

While wandering around the dark forest of Facebook and Linked in and Twitter, most of us realised we need to go somewhere safer.

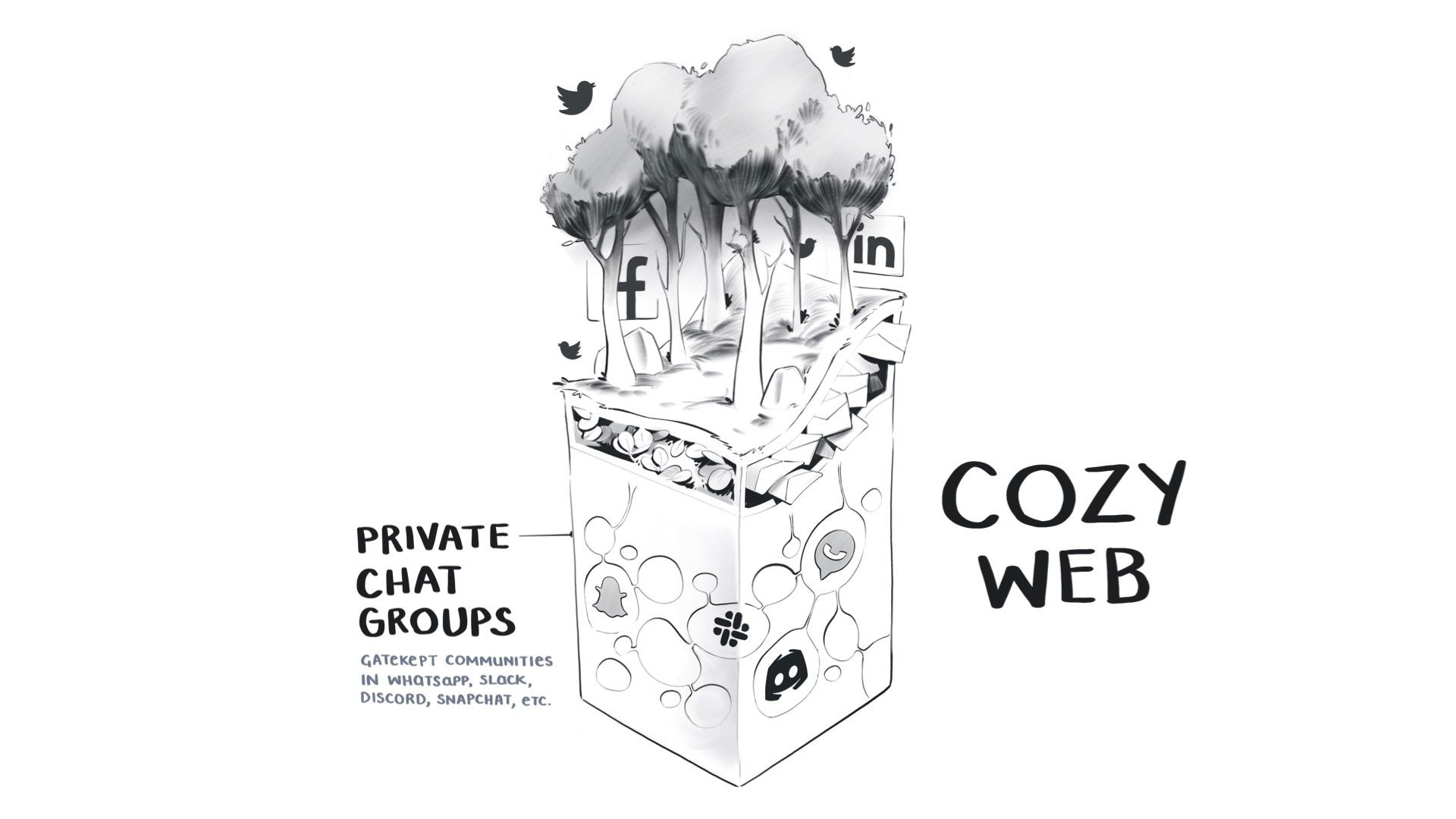

We end up retreating to what’s been called the “cozy web.”

This term was coined by Venkat Rao in The Extended Internet Universe – a direct response to the dark forest theory of the web. Venkat pointed out that we’ve all started going underground, as if were.

We move to semi-private spaces like newsletters and personal websites where we’re less at risk of attack.

However, even personal websites and newsletters can sometimes be too public, so we retreat further into gatekept private chat apps like Slack, Discord, and WhatsApp.

These apps allow us to spend most of our time in real human relationships and express our ideas, with things we say taken in good faith and opportunities for real discussions.

The problem is that none of this is indexed or searchable, and we’re hiding collective knowledge in private databases that we don’t own. Good luck searching on Discord!

My current theory is that the dark forest parts of the web are about to expand.

We now have what’s being called generative AI

These are machine-learning models that can generate content that before this point in history, only humans could make. This includes text, images, videos, and audio.

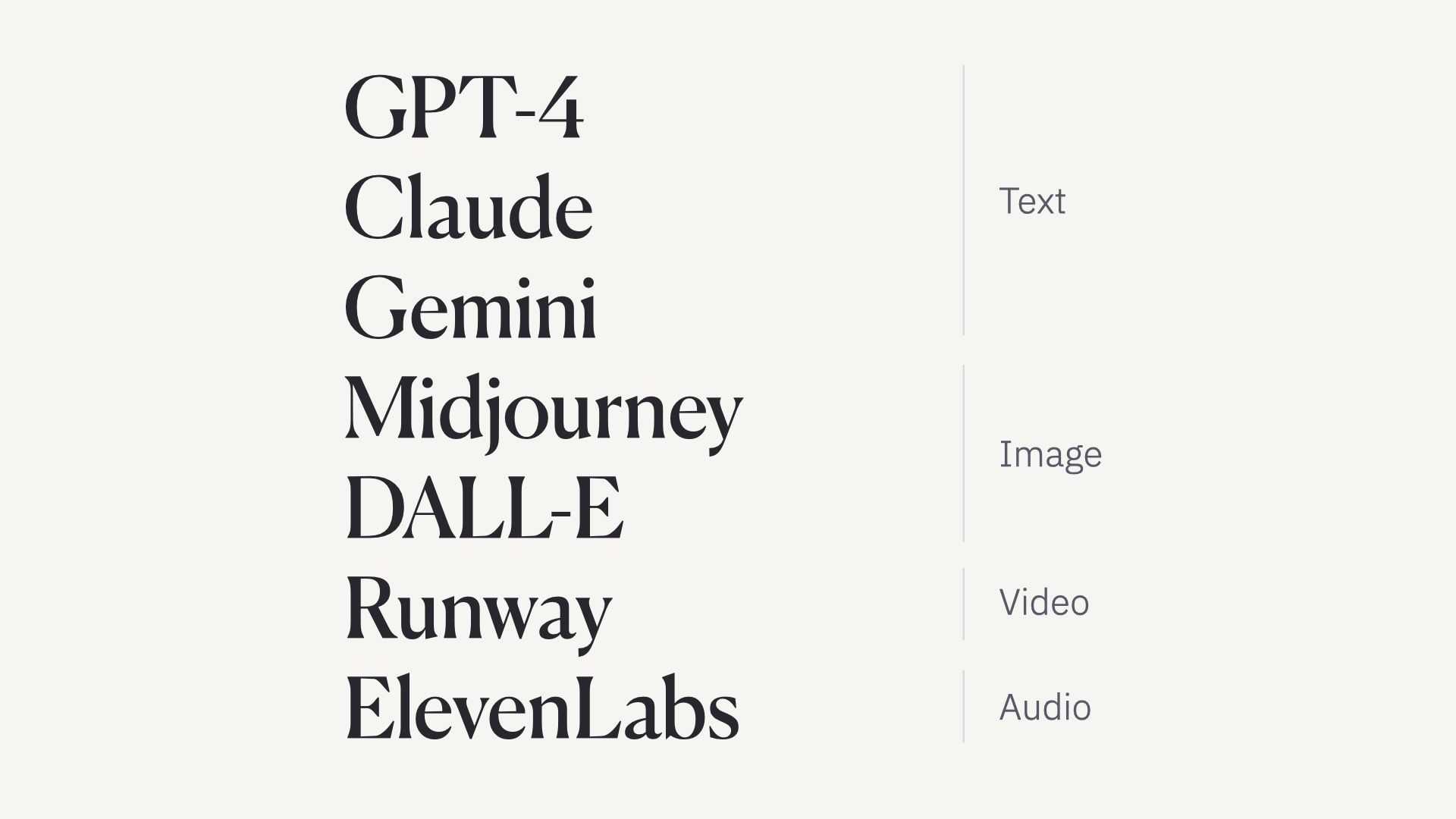

Here are some some popular models for each media type. I’m sure you’ve all heard of some of these.

Obviously, this is ChatGPT. We’ve all seen thousands of screenshots of this.

It’s a large language model that can generate huge volumes of human-like text in seconds.

I’m going to assume a fair amount of knowledge about language models in this crowd.

The key points to know are:

- Its outputs are generally indistinguishable from human-made text, roughly at a high school essay level. We should acknowledge that these outputs are astonishingly good. I’ll get to the flaws and weaknesses of language models later.

- They’re trained on a huge volume of text scraped primarily from the English-speaking web.

- All language models do is predict the next word in a sequence, which may sound simple but leads to all kinds of complex and potentially useful behaviour.

We can also generate images. These are outputs from Midjourney.

We can also do videos. This is a demo of OpenAI’s SORA model

This is still in the uncanny valley stage.

I’m not going to focus on video and image outputs for this talk. I’m just going to focus on language models.

Deepfakes are a problem, but I’m all full up on problems. Someone else is going to have to do that talk.

By now language models have been turned into lots of easy-to-use products. You don’t need any understanding of models or technical skills to use them. They come baked-into many existing popular tools like Photoshop or Notion.

The product category that concerns me most is content generators. These are tools designed for marketers and SEO strategists to easily create publishable content.

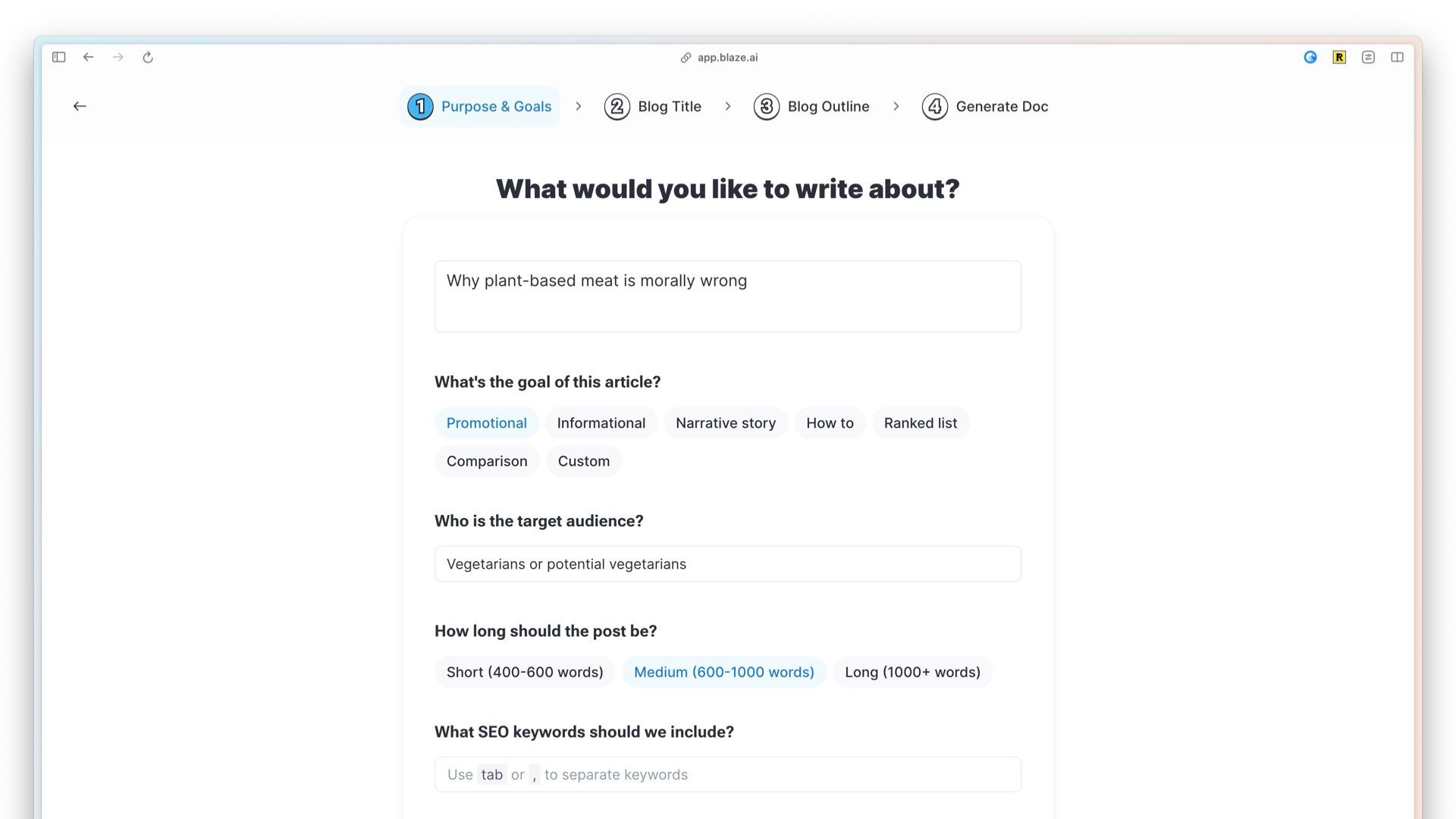

I’m going to pick on one called Blaze but there are plenty of other tools that do the same thing.

They tend to work like this: You type in what you want to write about. I’ve said “why plant-based meat is morally wrong” here. This isn’t an opinion I agree with but it sounds like a good topic for clickbait.

So I’ll have this model write an article for me.

And then it churns out 700 words on it. This is now ready for me to publish.

Which if I’m someone lobbying against carbon credits is handy.

I can generate 100 of these, optimise them for Google search terms, and shove them on the web.

A hard day’s advocacy done!

The quality and truthfulness of this is clearly questionable, but we’ll get to the problems with it later.

The point is this is very easy to do.

This isn’t limited to blog posts and articles. Any text that can be generated will.

They give you an array of convenient formats. Like presenting yourself on a dating site and wedding vows. Or “sharing tips and knowledge”. Though clearly not based off anything you’ve actually learned.

There’s every manifestation of this; Tweet generators, Linked In post generators, turn YouTube videos into tweets and vice versa.

You’re able to reuse content quite easily. This is all a marketer’s dream!

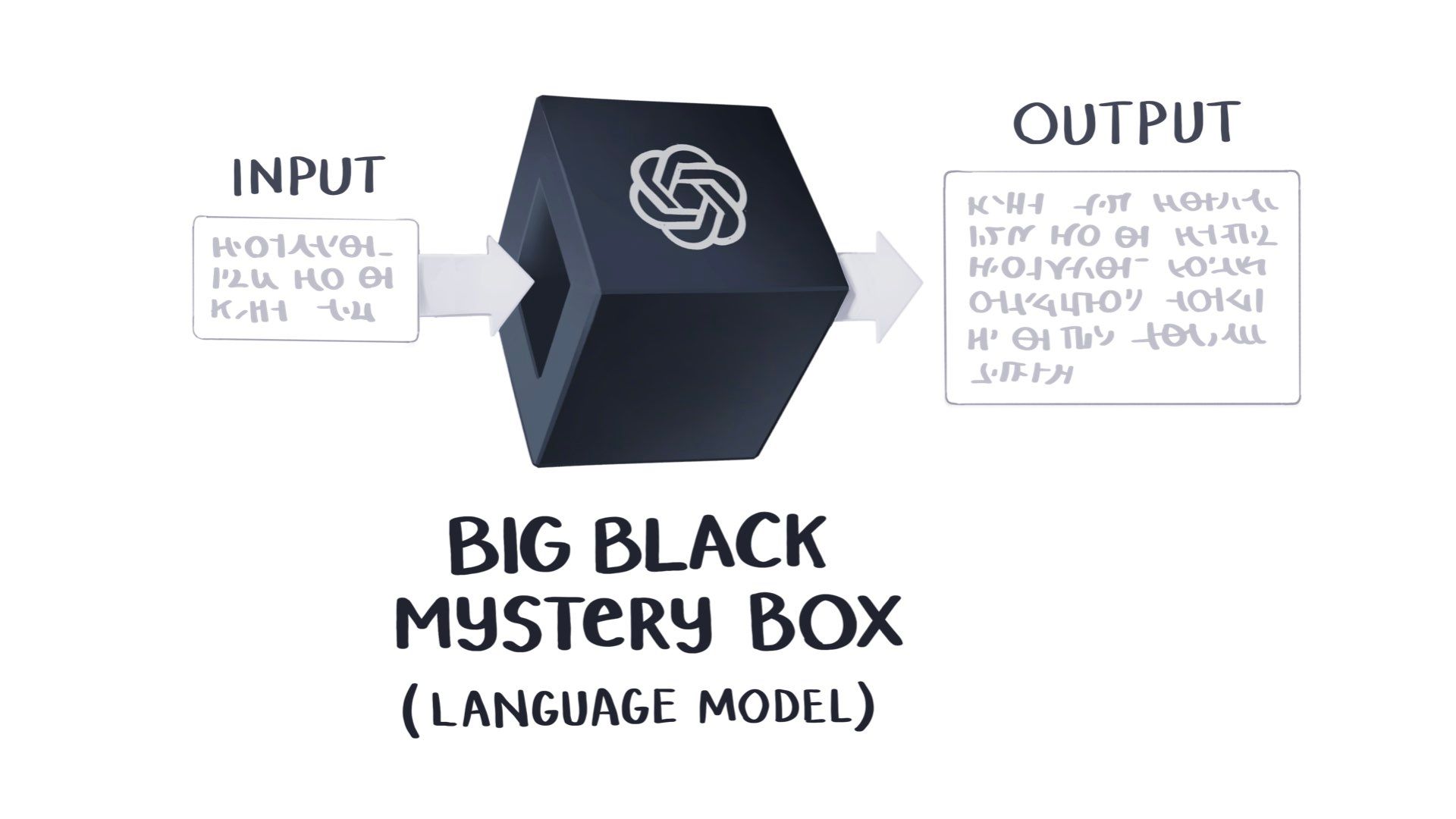

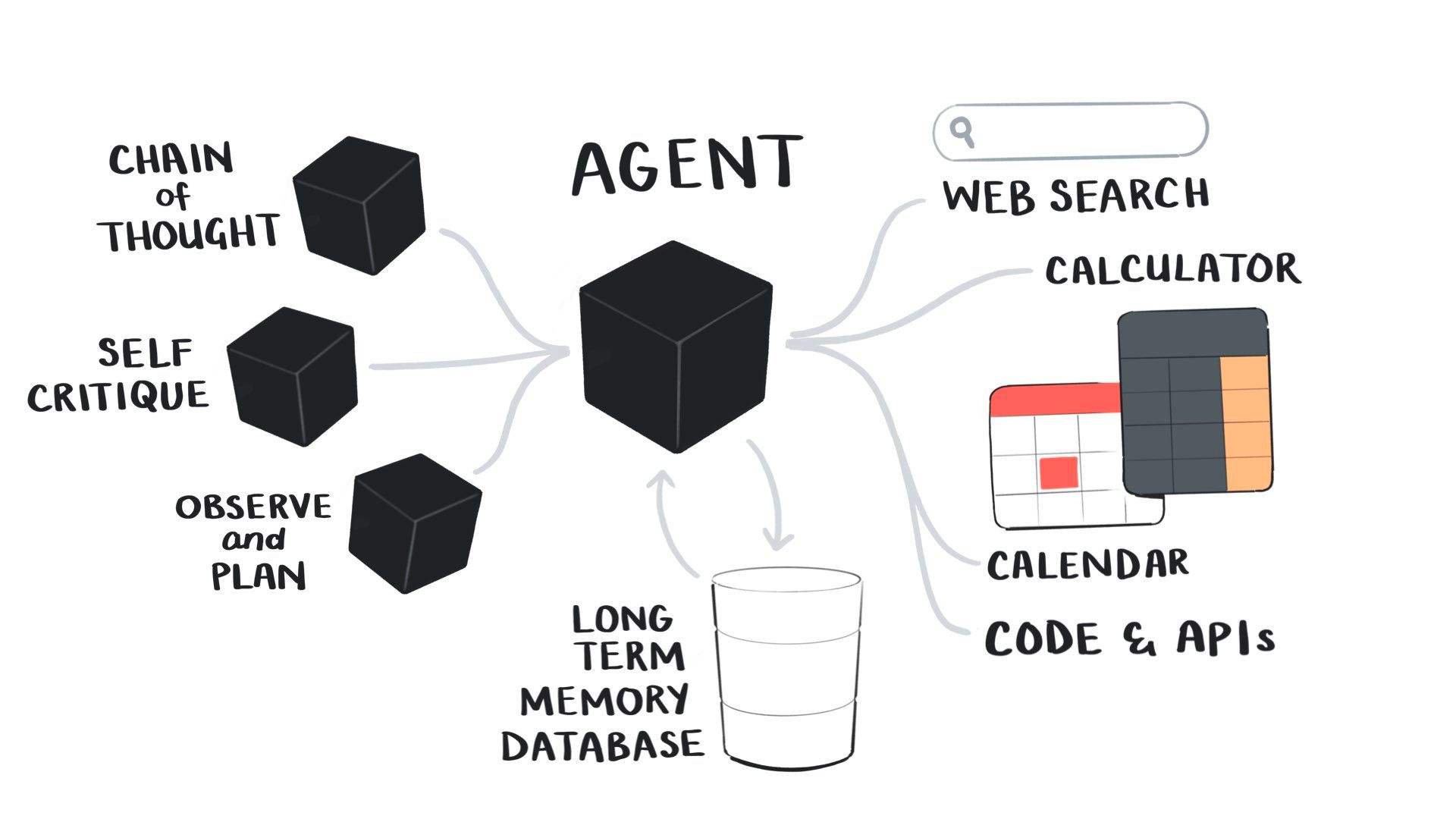

Most of the tools and examples I’ve shown so far have a fairly simple architecture.

They’re made by feeding a single input, or prompt, into the big black mystery box of a language model. (We call them black boxes because we don’t know that much about how they reason or produce answers. It’s a mystery to everyone, including their creators.)

And we get a single output – an image, some text, or an article.

We can scale that up to many outputs.

Most companies that make language models have an API you can hit. So we can ask for 1,000 or 100,000 articles.

But we’re still limited in how sophisticated we can get with these outputs.

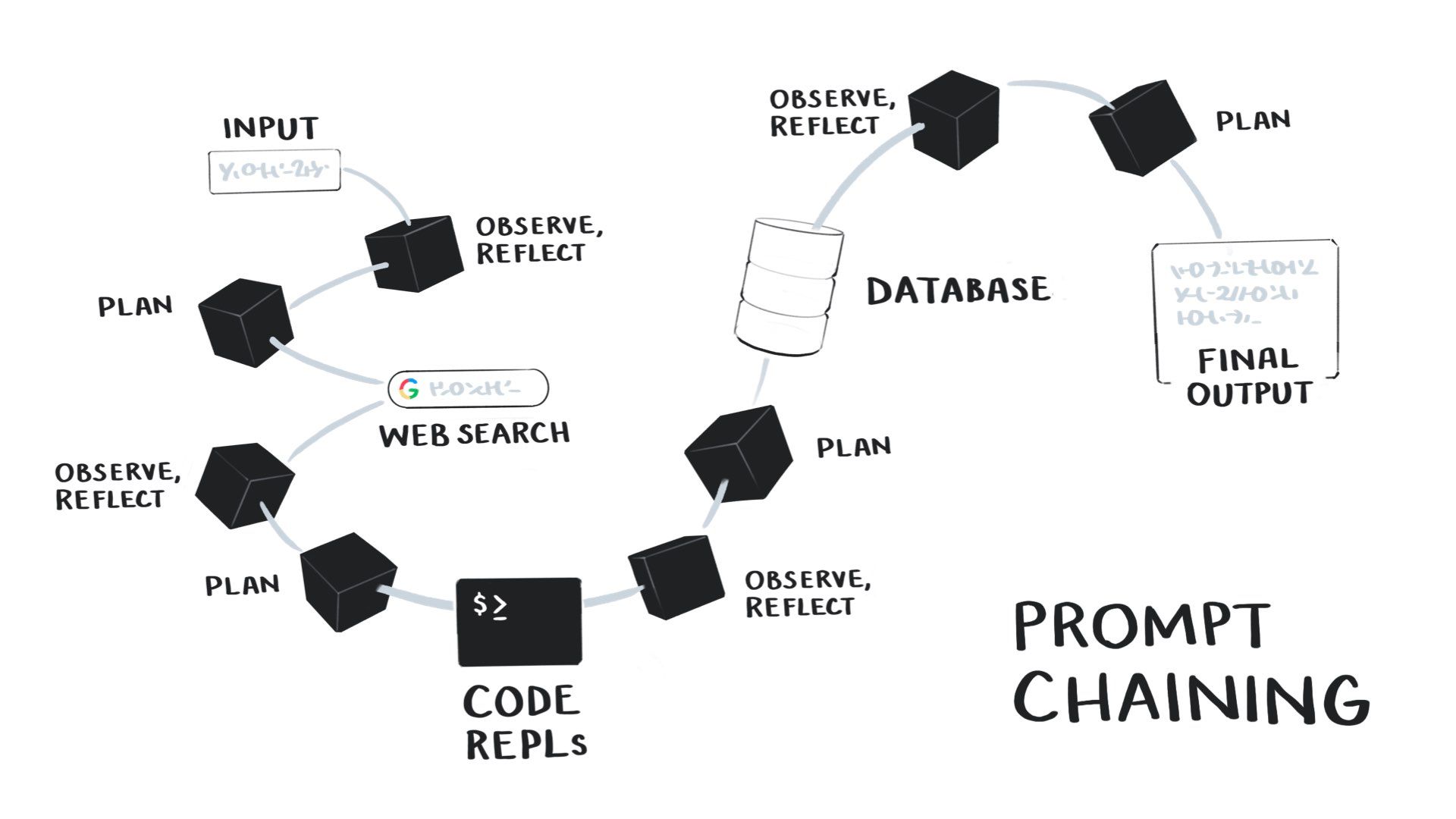

Recently, people have been developing more sophisticated methods of prompting language models, such as “prompt chaining” or composition.

Ought has been researching this for a few years. Recently released libraries like LangChain make it much easier to do.

This approach solves many of the weaknesses of language models, such as a lack of knowledge of recent events, inaccuracy, difficulty with mathematics, lack of long-term memory, and their inability to interact with the rest of our digital systems.

Prompt chaining is a way of setting up a language model to mimic a reasoning loop in combination with external tools.

You give it a goal to achieve, and then the model loops through a set of steps: it observes and reflects on what it knows so far and then decides on a course of action. It can pick from a set of tools to help solve the problem, such as searching the web, writing and running code, querying a database, using a calculator, hitting an API, connecting to Zapier or IFTTT, etc.

After each action, the model reflects on what it’s learned and then picks another action, continuing the loop until it arrives at the final output.

This gives us much more sophisticated answers than a single language model call, making them more accurate and able to do more complex tasks.

This mimics a very basic version of how humans reason. It’s similar to the OODA loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act).

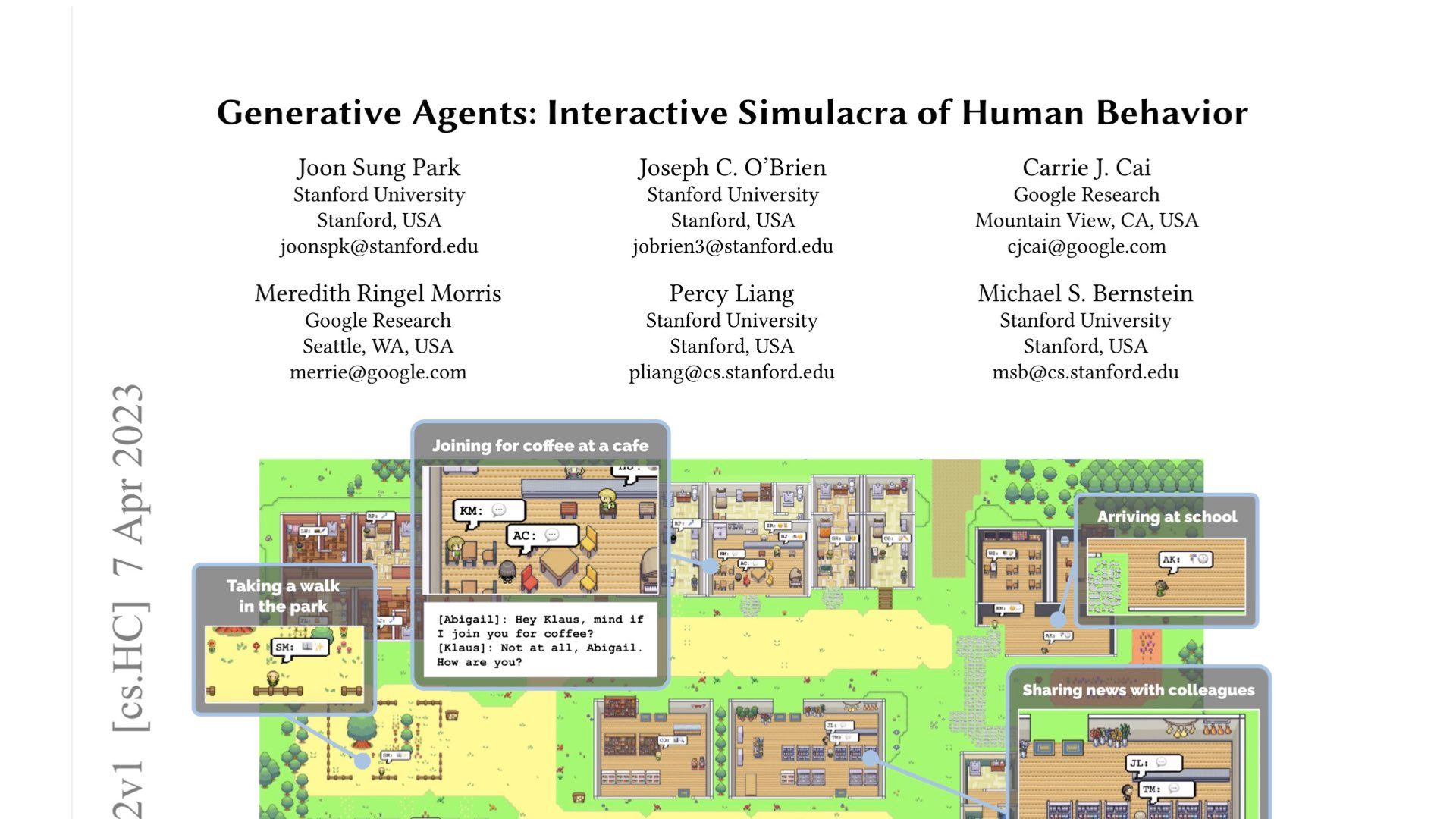

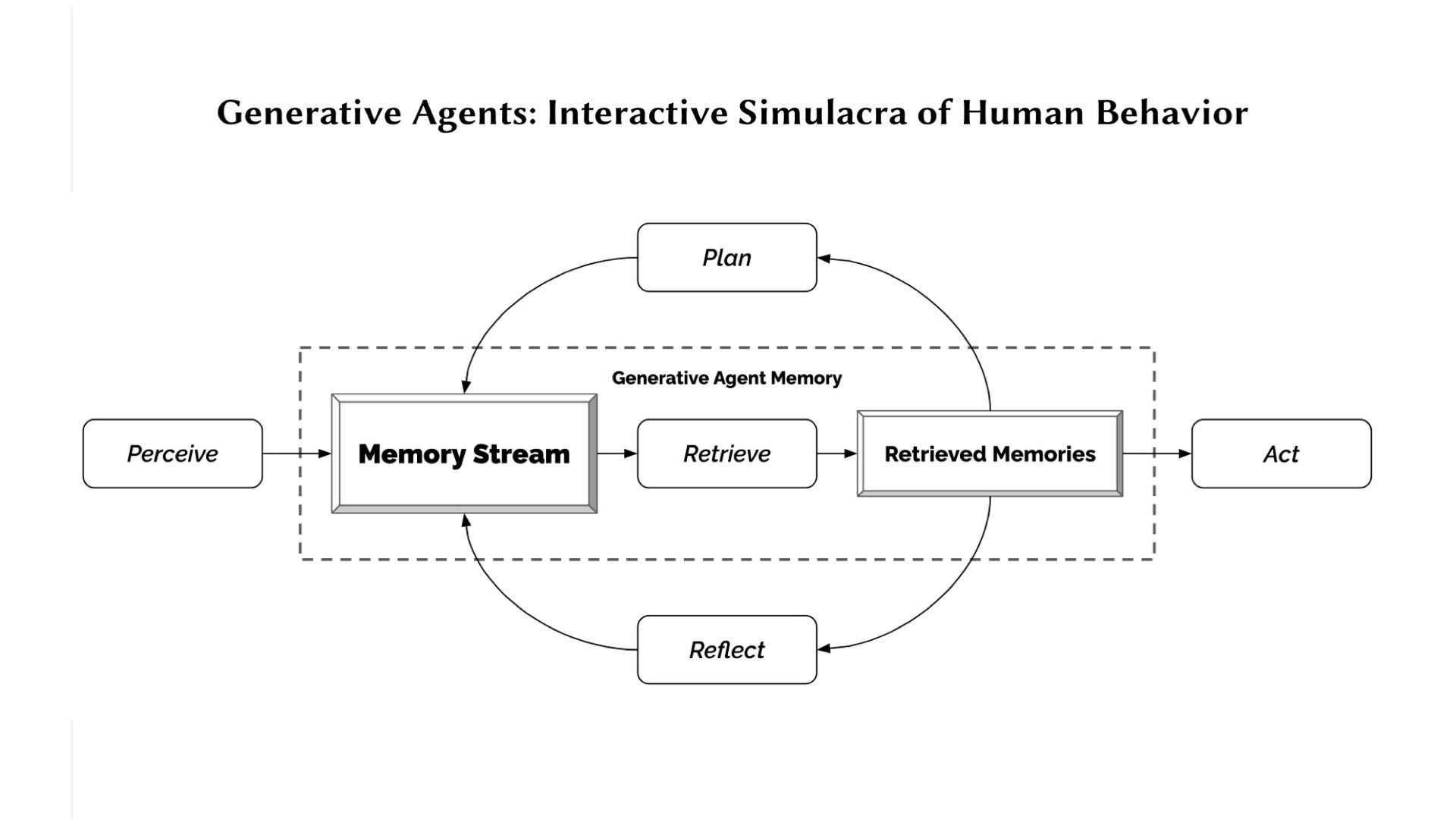

Recently, people have taken this idea further and developed what are being called “generative agents”.

Just over two weeks ago, this paper “ Generative Agents : Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior” came out outlining an experiment where they made a sim-like game (as in, The Sims) filled with little people, each controlled by a language-model agent.

These language-model-powered sims had some key features, such as a long-term memory database they could read and write to, the ability to reflect on their experiences, planning what to do next, and interacting with other sim agents in the game.

And this architecture produced very compelling and believable human behaviours.

The agents would perform everyday tasks such as cooking breakfast, stopping if something is burning, chatting to one another, forming opinions, and reflecting on their day.

Additionally, these agents exhibited more emergent social behaviours, such as planning and attending a Valentine’s Day party and asking each other out on dates.

There’s a new library called AgentGPT that’s making it easier to build these kind of agents. It’s not as sophisticated as the sim character version, but follows the same idea of autonomous agents with memory, reflection, and tools available. It’s now relatively easy to spin up similar agents that can interact with the web.

I think we’re about to enter a stage of sharing the web with lots of non-human agents that are very different to our current bots – they have a lot more data on how behave like realistic humans and are rapidly going to get more and more capable.

Soon we won’t be able to tell the difference between generative agents and real humans on the web.

Sharing the web with agents isn’t inherently bad and could have good use cases such as automated moderators and search assistants, but it’s going to get complicated.

Now, why is this a problem?

I’m only going to focus on how this will be a problem for human relationships and information over the web.

Anything else – like how we might all end up unemployed or dead soon – is beyond my pay grade.

The cost of creating and publishing content on the web just dropped to almost zero.

Humans are expensive and slow at making content. We need time to research, read, think, and clumsily string words together. And then we insist on taking more time to eat, sleep, socialise, and shower.

Generative models, on the other hand, write much faster, don’t need time off, and don’t get bored.

ChatGPT currently costs a fraction of a cent ($0.002) to generate 1000 tokens (~words), meaning that it would cost only two cents to generate 100 articles of 1000 words. If we used a more sophisticated architecture like prompt chaining the cost would certainly be higher, but still affordable.

Given that these creations are cheap, easy to use, fast, and can produce a nearly infinite amount of content…

…I think we’re about to drown in a sea of informational garbage.

We’re going to be absolutely swamped by masses of mediocre content.

Every marketer, SEO strategist, and optimiser bro is going to have a field day filling Twitter and Facebook and Linked In and Google search results with masses of keyword-stuffed, optimised, generated crap.

This explosion of noise will make it difficult to hear any signal. We’ll need to find more robust ways to filter our feeds and curate good-quality work.

While we already have tools to deal with spam and filter low-quality content, I think this new, more sophisticated of junk will leak through. I expect it will take a few years to get our content moderation, filtering, and defence systems to catch up.

Meta note: This image was made in Midjourney. It’s the only AI-generated image I’m using in this talk. I mostly wanted to show that AI can do hands now – progress!

We can tell this is already happening because spammers and scammers are lazy as fuck.

This recent Verge article: “‘ As an Al language model ’: the phrase that shows how Al is polluting the web” pointed out that the phrase “as an AI language model” is showing up in all kinds of places: Amazon reviews, Yelp reviews, Tweets, and LinkedIn posts.

This is a common phrase that shows up in ChatGPT outputs. As in “as an AI language model, I do not have any political opinions”

The fact spammers couldn’t even be bothered to remove this obvious giveaway from their outputs shows the level of care and detail they’ll put into future work.

Last week a NewsGuard report came out detailing how they found 49 entirely AI generated but legitimate looking “news” websites, all publishing misinformation that ranks well on Google

There’s been a surge in self-published books on Amazon…

The New York Times did a report on how the travel guidebook category was being flooded with generated crap.

The book content scored highly on their generative AI dectectors, and the authors were made up people with generated profile images.

Amazon has started limiting the number of self-published books to 3 a day in response.

The tell-tale phrase “as an AI language model” shows up all the time in Amazon reviews, Yelp reviews, Tweets, and LinkedIn posts.

Most are very boring attempts to get ChatGPT to write engaging LinkedIn posts

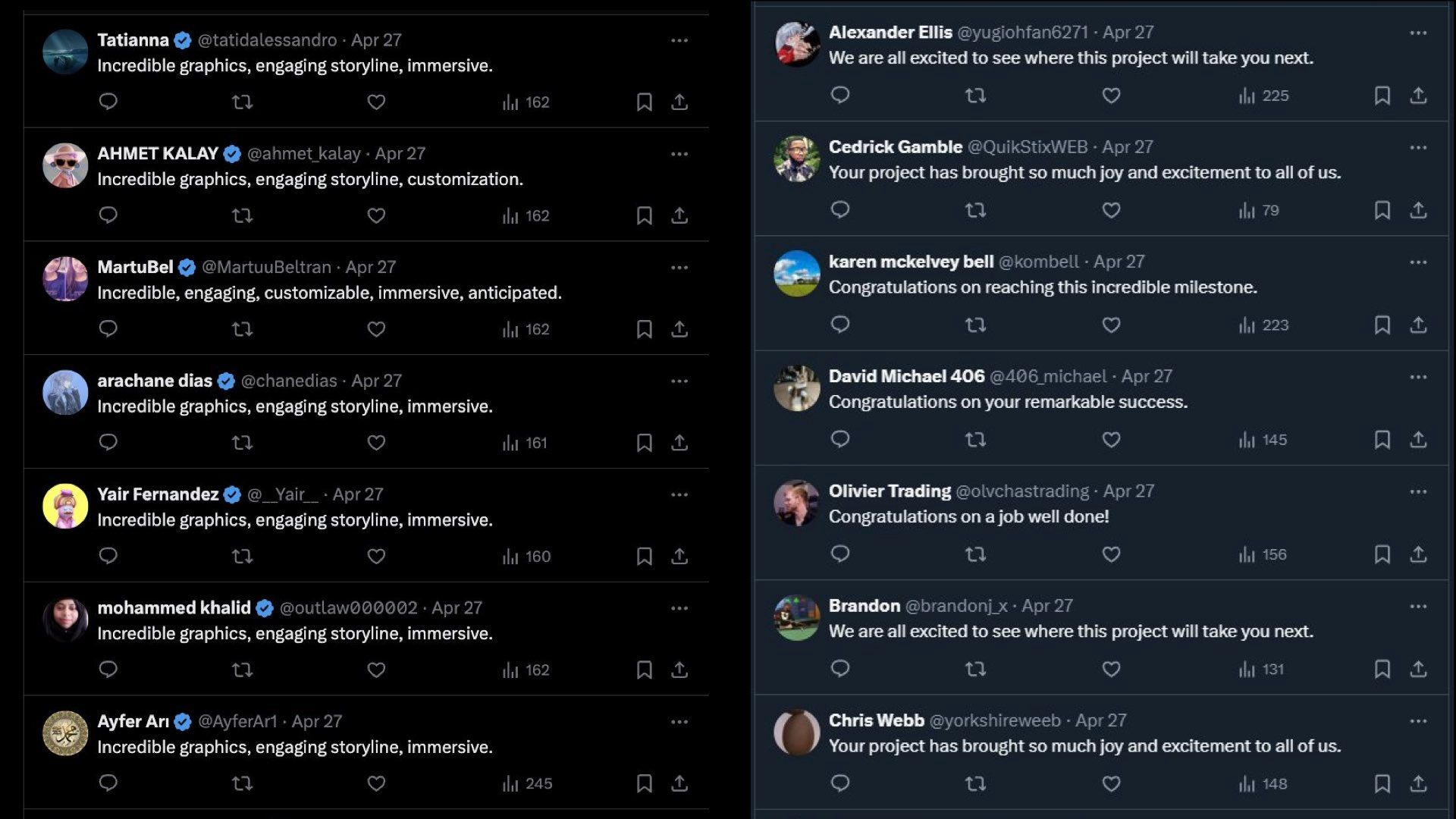

One of my favorite Twitter accounts at the moment is dead internet at its finest which collects examples of generated crap

Reply sections like this Bots replying en mass to content with: “Incredible graphics, engaging storyline, immersive.” “Congratulations on your remarkable success.”

Facebook is a whole different story. I hadn’t been on in about a decade. Found a paper published in March by two Stanford researchers looking at AI generated spam and scam images. Found hundreds of pages of generative content farms. These pictures of AI generated children all have a million engagements or more on them. Despite being obviously fake This paper sent me down a awful rabbit hole… Where I learned if there’s one thing boomers on Facebook love, it’s children making things, and Jesus.

Here’s a generated AI child making a rather unbelievable Jesus sand sculpture with 11,000 enaggaements and over 300 comments

And another AI generated child in a slum who made a Coca-cola Jesus? Very entreprenrial of him. The spirit of capitalism alive and well here. Again, thousands of engagements, hundreds of comments

And finally… I cannot explain what this is or why, but this crab Jesus has over 200,000 engagements and 4000 comments There are many other more disturbing examples I didn’t have the stomach to put in. So the examples I’m showing here are extremely unsophisticated. This is bot-generated-nonsense with bots reacting to it. We’ll probably be able to filter out and ignore the vast majority of this. I’m more worried about the more sophisticated version of this.

Let’s look at some hypothetical scenarios of how this might unfold.

This is Nigel. He’s written a book on ‘Why Nepotism is Great’ and he wants to be a bookfluencer.

We’re going to give him the benefit of the doubt and assume he’s actually written this book and not prompted it into existence.

So he spins up an agent

And tells it to promote the book (not so different to a traditional book agent!)

And then gives it access to all his social media accounts via APIs or something like Zapier.

The agent takes a moment to strategise. And then gets to work.

It generates and schedules a steady stream of tweets based on the book content. Then turns those into posts optimised for LinkedIn and Facebook. It then writes and schedules a newsletter every week for 6 months. Then sets up a Medium account and republishes those as articles. It moves onto creating a set of addictive TikTok videos, a 24-part series for YouTube, and generates a bunch of podcast episodes that use Nigel’s voice (trivial to do at this point). And finally finds other people writing about nepotism and starts replying to everything they publish on Twitter, LinkedIn, etc. in order to

This is not that different to what Nigel could do. And the agent knows not to make tons of content, lest it set off any red flags from content moderators. So it seems plausible this all could have been Nigel’s doing.

Without an agent, 99% of Nigel’s wouldn’t have the time, energy and motivation to do this, even if they had written a book. And they certainly couldn’t keep up this consistency of output. I also expect Nigel’s agent will write quite compelling, accurate content. Perhaps better than Nigel.

So now instead of only 1% of people having the time and energy to be prolific self-promoters.

99% of people have the capacity to publish this mass of content to the web. It doesn’t mean they will, but they could.

Clearly, we already have lots of spam on the web now that we’re able to filter out and ignore. But I think the scale and quality of this new kind is something we’re not prepared for.

Now imagine how this plays out with a political group with a specific agenda to push…

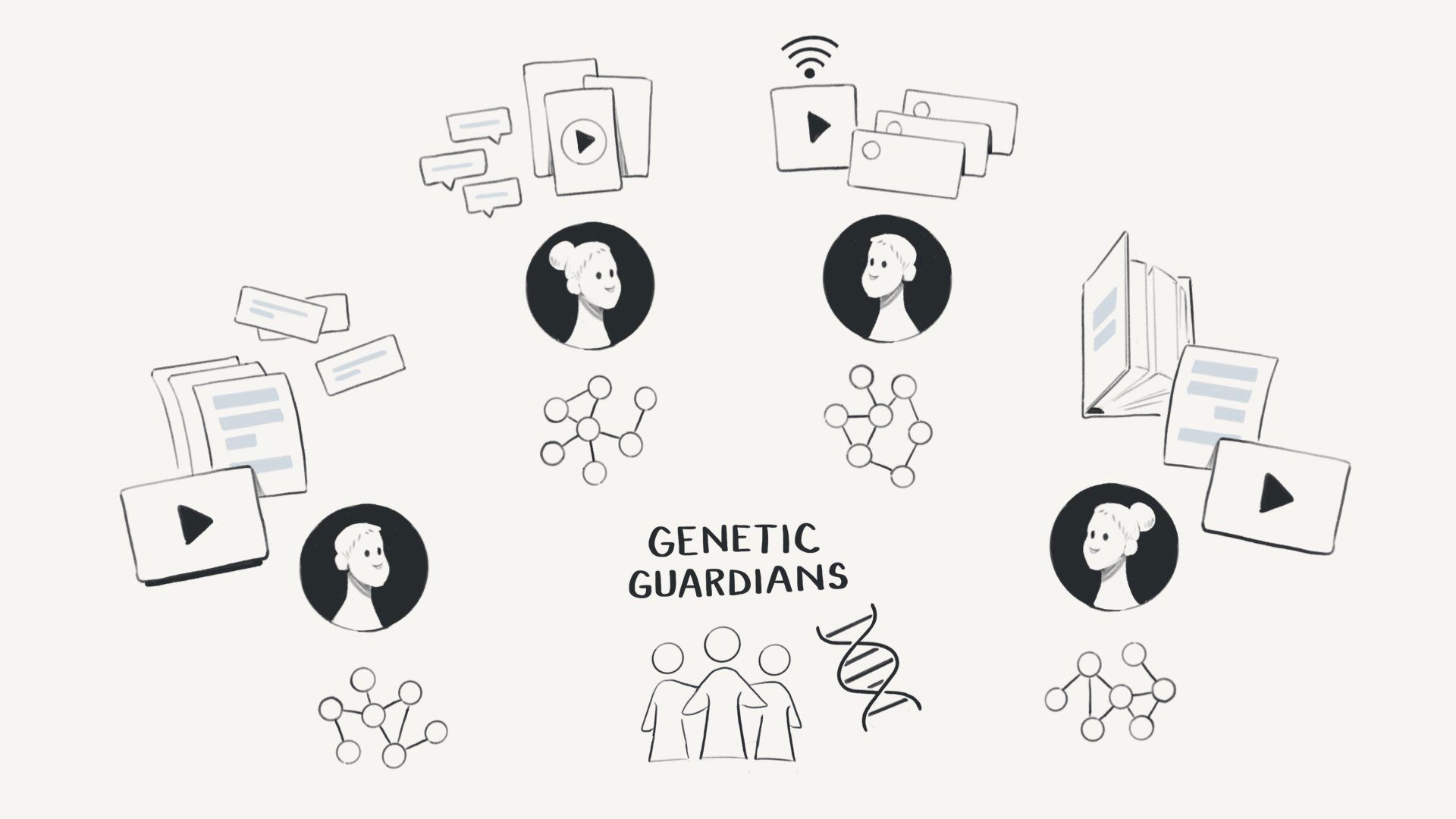

So here’s Genetic Guardians – they’re a bunch of political lobbyists who strongly believe in gene editing. And want to spread the good word.

But they understand scale in a way Nigel doesn’t.

They spin up 1000 agents.

And tell each of them to go be influencers. They should appear to be real, consistent people who have accounts on most major social media platforms. They have their own websites and Twitter accounts. And they behave just like the other humans on the web.

But each influencer is a one-person media machine making engaging and educational content about gene editing. They publish books. They make mini-docs on YouTube. They host each other on their podcasts.

They essentially build an influencer content ring around gene editing.

And they still don’t set off any suspicions of being bots or content moderation flags. Individually, they all appear to make a reasonable, human amount of content.

This is almost doable right now. It would certainly be a bit expensive to do at this scale. But we should expect costs to drop and there are some well-funded lobbying groups out there. I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s already happening.

I have some good news though.

This has all been a bit dark. Let’s take a breath.

This might not be a problem.

This is only a problem if…

…we want to use the web for very particular purposes.

Such as facilitating genuine human connections, pursuing collective sense-making and building knowledge together, and ideally grounding our knowledge of the world in reality.

So, if you don’t care about these things, don’t worry about generative AI! Everything will be fine!

We’re about to have much more engaging content on social media. TikTok will be lit.

However, I’m quite keen on these outcomes; I write on the web a lot, I’m a big proponent of people publishing personal knowledge online, and I encourage everyone to do it.

I keep banging on about digital gardening which is essentially having your own personal wiki on the web.

The goal here is to make the web a space for collective understanding and knowledge-building, something lots of other speakers here have touched on. Which requires that we’re able to find, share, and curate high-quality, reliable, and insightful information.

I’m worried that generative agents threaten that, at least in the short term.

When I talk to people about my worries, I always get this question:

Why does it matter if a generative model made something rather than a human?

In most cases, language models are more accurate and knowledgeable than most humans. Benchmarks have shown this. At least when it comes to referencing well-documented facts. They’re frankly better writers than a lot of us.

Surely, having more generated content on the web would make it a more reliable and valuable place for all of us?

And I’m sympathetic to this point…

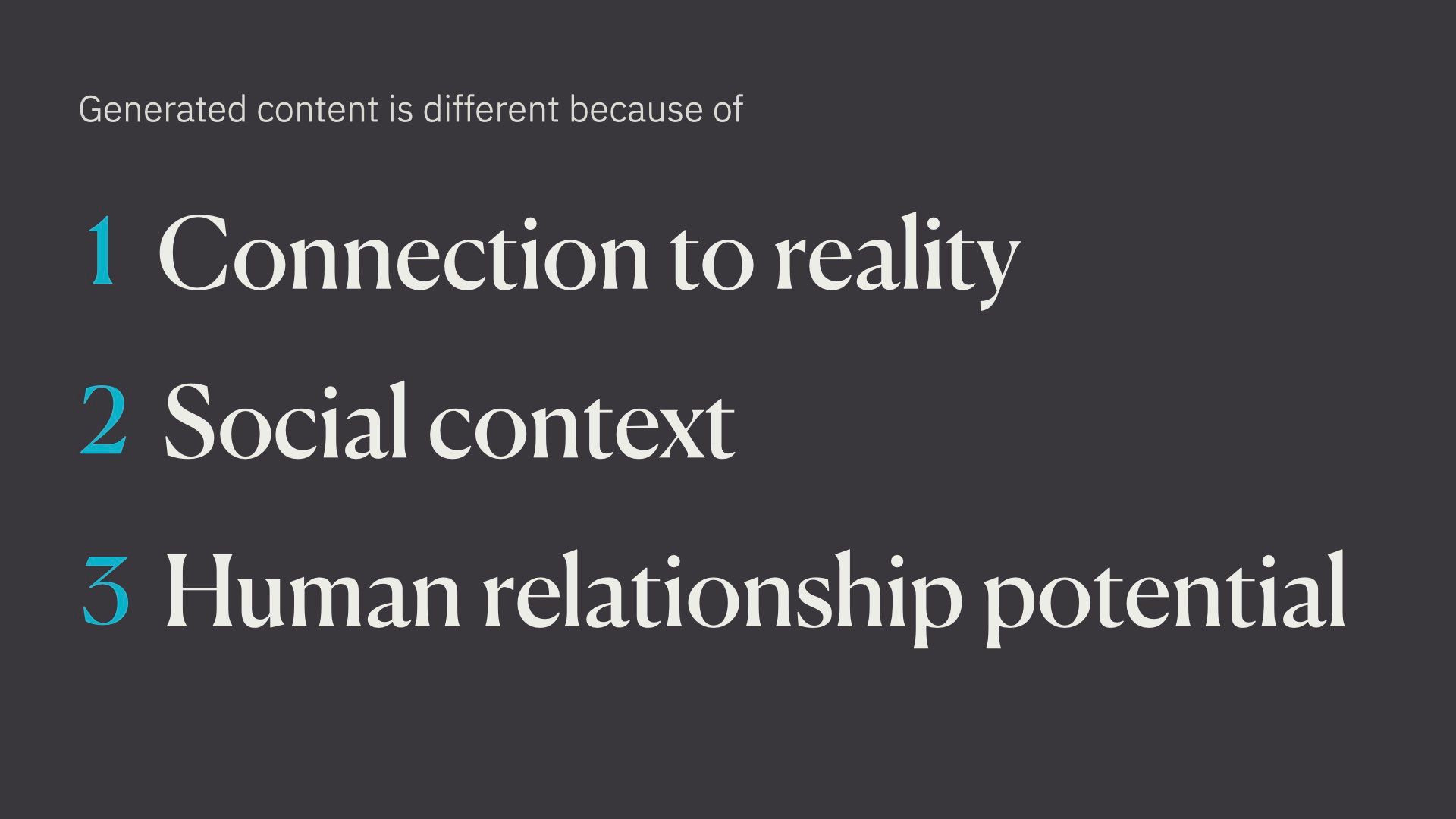

But there are a few key differences between content generated by models versus content made by humans.

First is its connection to reality. Second, the social context they live within. And finally their potential for human relationships.

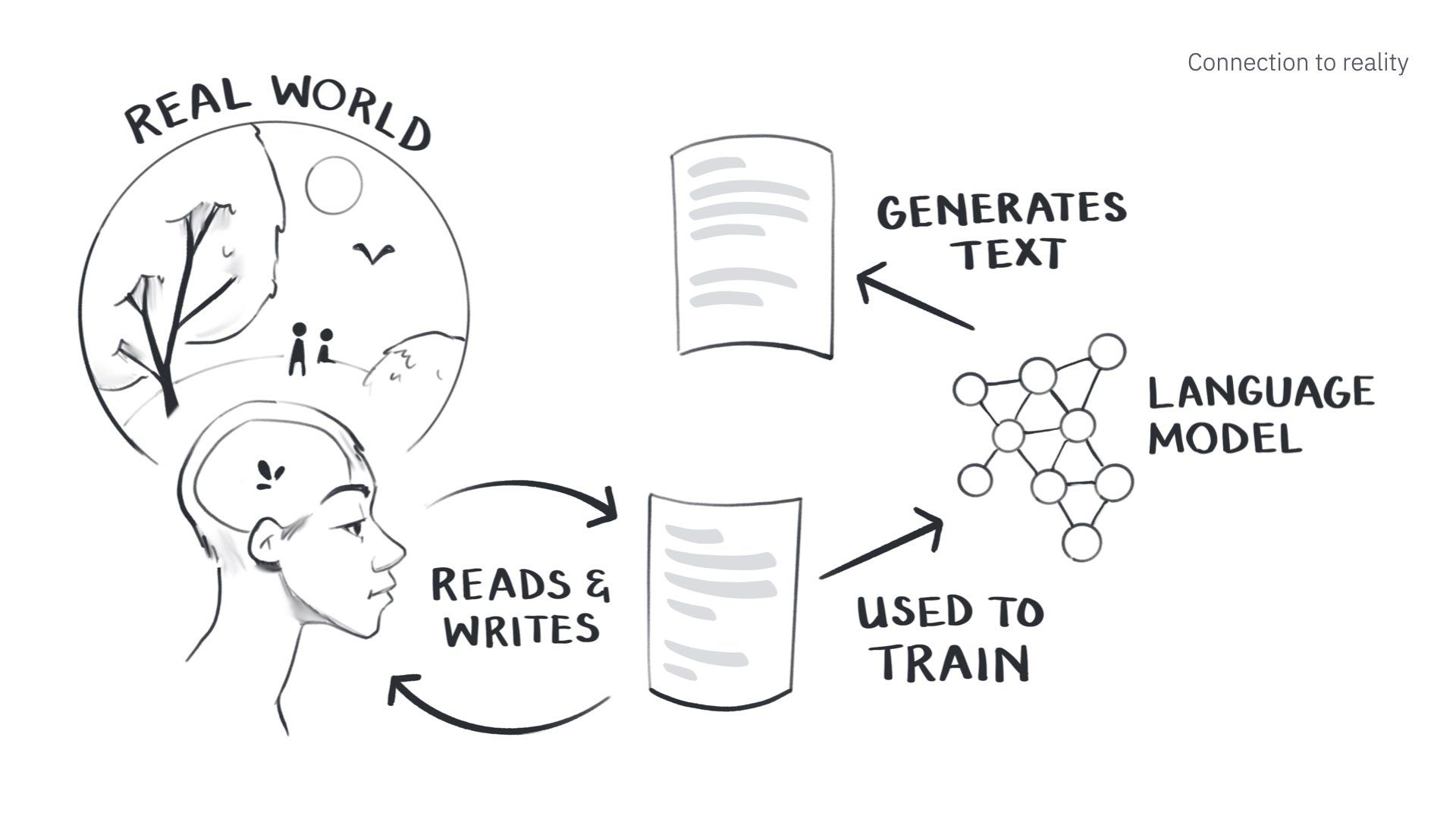

First, generated content is different because it has a different relationship to reality than us.

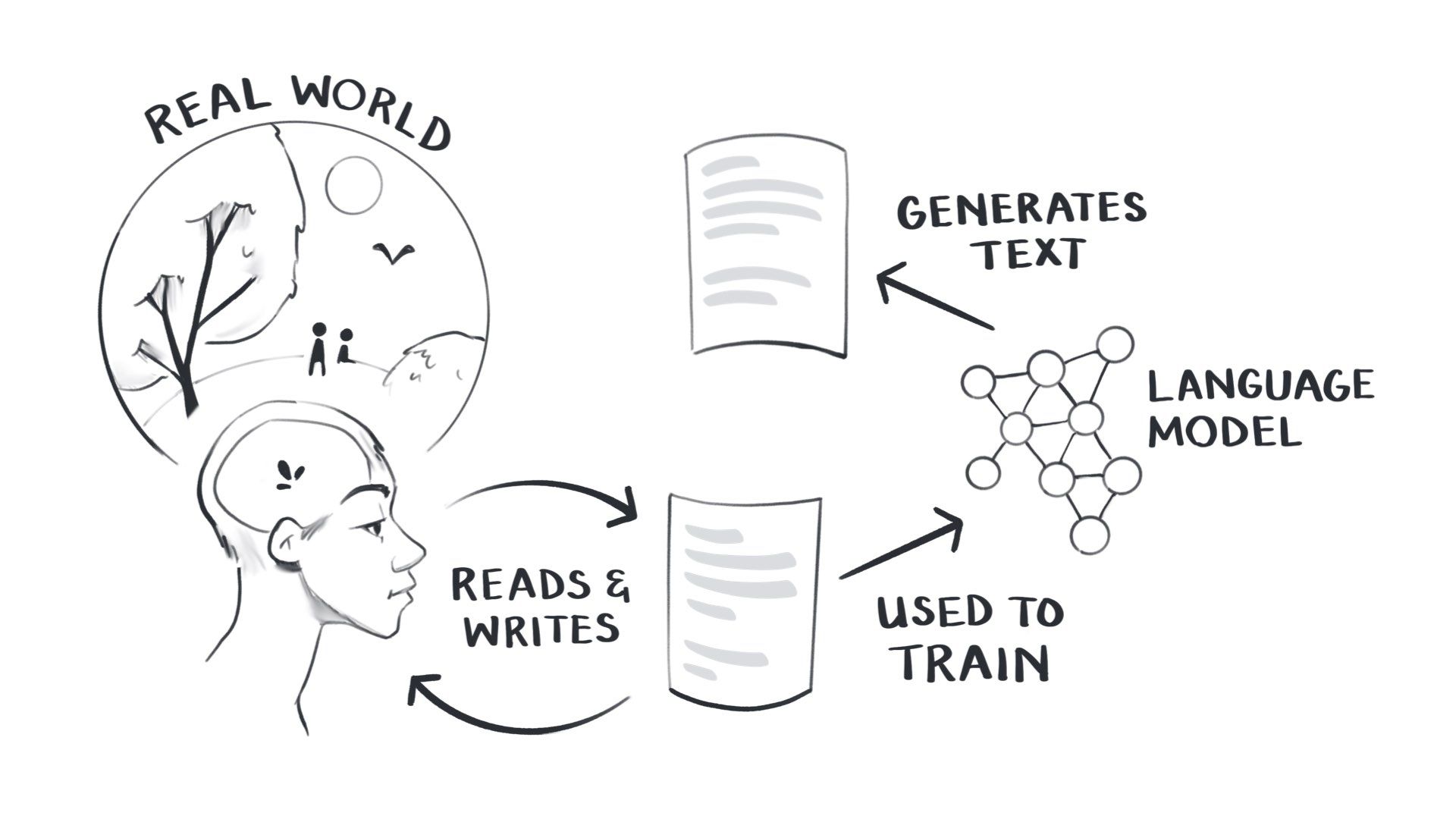

We are embodied humans in a shared reality filled with rich embodied sensory information.

When we read, we compare other people’s accounts of reality against our own experiences. We question whether their views align with ours. And then we write our own accounts.

In doing this, we are all participating in this beautiful cycle of trying to make sense of everything together. This is the core of all science, art, and literature. We are trying to understand and teach each other things through writing.

We have now fed this enormous written record into large language models, encoding a bunch of patterns in their networks, creating a representation of the existing written knowledge of humanity.

This model can now generate text that is predictably similar to all the text it has seen before.

But the tricky bit is trying to figure out how much this generated text relates to reality.

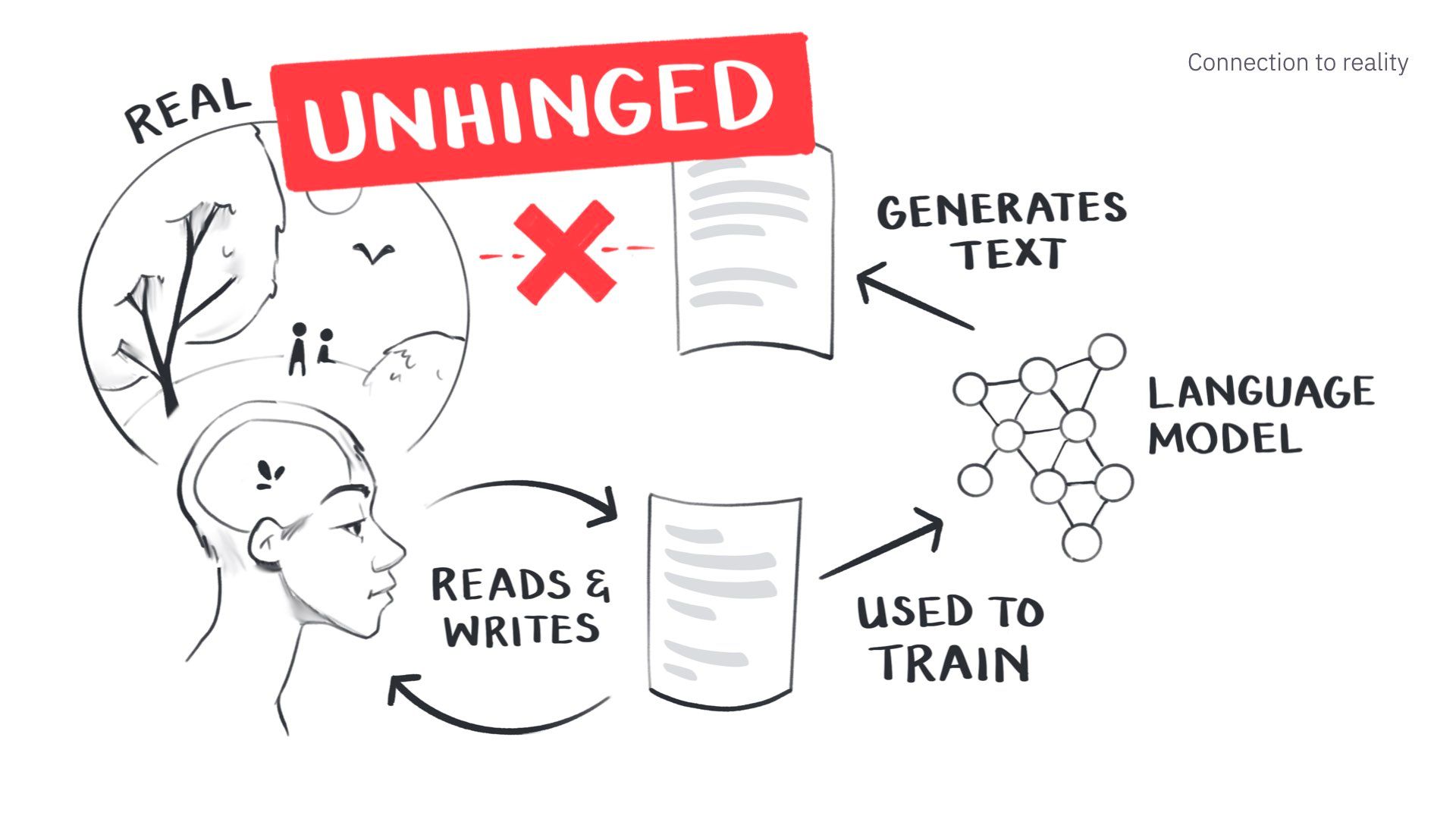

In some sense, it’s fully UNHINGED.

The model cannot check its claims against reality because it can’t access reality.

But it’s a bit like a fuzzy memory of reality.

It is based off what we’ve written about the world, but can’t validate its claims.

We politely call it “hallucination” when language models say things that don’t reflect reality.

In ways, it’s like a terribly smart person on some mild drugs. They’re confused about who they are and where they are, but they’re still super knowledgeable.

This disconnect between its superhuman intelligence and incompetence is one of the hardest things to reconcile.

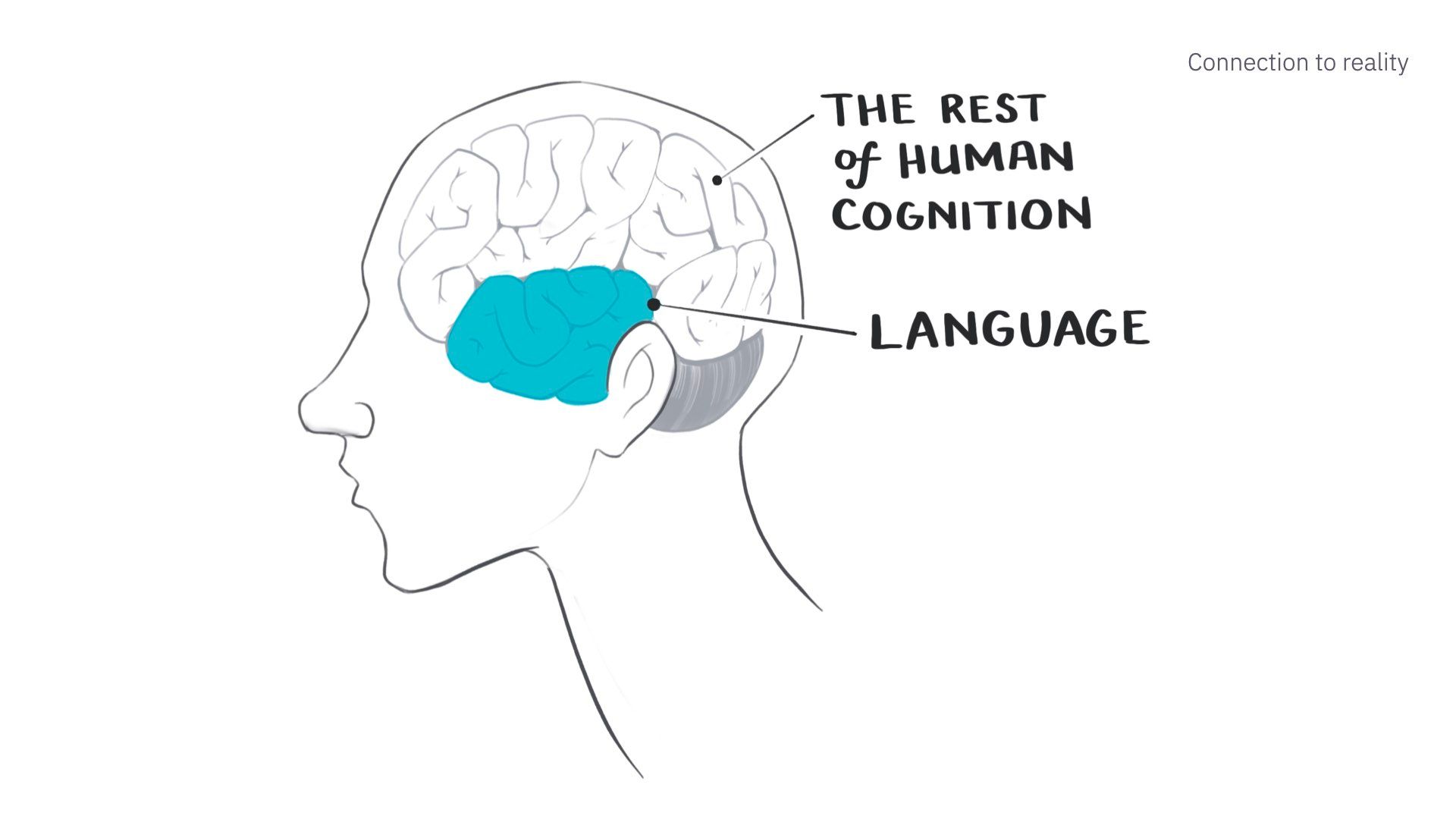

A big part of this limitation is that these models only deal with language.

And language is only one small part of how a human understands and processes the world.

We perceive and reason and interact with the world via spatial reasoning, embodiment, sense of time, touch, taste, memory, vision, and sound. These are all pre-linguistic. And they live in an entirely separate part of the brain from language.

Generating text strings is not the end-all be-all of what it means to be intelligent or human.

So simulated humans that can only deal with language are missing a big part of what we perceive as human “reality.”

Language models are also different in their social context. In that they have a strange relationship to our social world.

Everything we say is situated in a social context. I’m assuming everyone in this room has an usually high level of technical literacy. I don’t talk to my writer friends, or my aunt in the same way I’m going to talk to you. We are always evaluating the amount of shared context we have with people we’re talking to - it changes how we communicate.

If I met someone from Shakespearean England, we’d have some trouble communicating because we share less context. We don’t just speak in different dialects, we have different morals and values, we have different assumptions about how society works and how science works.

The point is there is no truth or knowledge outside of social context. Everything we say is contextual and relies on a shared social world.

But a language model is not a person with a fixed identity.

They know nothing about the cultural context of who they’re talking to. They take on different characters depending on how you prompt them and don’t hold fixed opinions. They are not speaking from one stable social position.

This leads some people to claim they’re objective or more reliable than humans with biases.

But they in fact do represent a very particular way of seeing the world.

We trained them primarily on text scraped from the web. They’re of course also trained on books and Wikipedia, but it’s a far smaller percentage of the training data.

This means they primarily represent the generalised views of a majority English-speaking, western population who have written a lot on Reddit and lived between about 1900 and 2023.

Which in the grand scheme of history and geography, is an incredibly narrow slice of humanity.

This clearly does not represent all human cultures and languages and ways of being.

We are taking an already dominant way of seeing the world and generating even more content reinforcing that dominance.

We don’t have enough data from people who have lived in different historical periods or minority cultures with less written content to represent them in current models.

This hopefully improves with time, but it’s hard to solve with limited data.

If I put my anthropologist hat on and look at this problem it feels exceptionally tragic.

Our entire discipline tries to expand the collective understanding of how diverse human cultures can be. We try to help people realise both how unified we are as a species, but also how flexible and adaptable human cultures can be – far weirder and more wonderful than we can imagine.

This is captured well in this quote from Tim Ingold, a well-known and brilliant anthropologist: “Every way of life represents a communal experiment in living. The world itself is never settled in its structure and composition. It is continually coming into being.”

Generating a mass of content from a very particular way of viewing the world funnels us down into a monoculture. Which feels like shutting down a ton of possibilities and diversity for all the ways human culture might unfold in the future.

Not to mention all the existing cultures and languages we might lose in this process.

Lastly, generated content lacks any potential for human relationships.

When you read someone else’s writing online, it’s an invitation to connect with them. You can reply to their work, direct message them, meet for coffee or a drink, and ideally become friends or intellectual sparring partners. I’ve had this happen with so many people. Highly recommend.

There is always someone on the other side of the work who you can have a full human relationship with.

Some of us might argue this is the whole point of writing on the web.

This isn’t the case with generated writing.

This is a still from the film ‘Her’ which is now the canonical reference for para-social relationships with AIs.

In it, Joaquin Phoenix has a wonderful relationship with his personal AI. He talks to her via an earpiece all day, grows increasingly distant from the humans around him, and eventually falls in love. The AI then grows bored of him and his tiny human mind and leaves.

This is a good lesson about the potentially unfulfilling outcomes we face if we try to form emotional relationships with AI.

But some people took this as a suggestion rather than a dark premonition…

This is Replika , a real service that creates an “AI companion” for you. Here agents are being used to create faux friends or romantic partners.

Obviously, generative models cannot fulfill all the needs humans have in relationships. They cannot hug you, come to your birthday party, truly empathise with your situation, or tell you about their experiences grounded in the real world.

In the same way generated content can’t facilitate real, fulfilling human relationships.

So that all sounds quite bad. Let’s do some more deep breaths.

I now want to talk about possible futures.

This is going to be a non-comprehensive, not mutually exclusive list of themes and trends. I’m guessing many of these will happen in parallel over the next 5 years. I’m not dumb enough to predict any further out than that.

First, we’re all about to spend a lot of time thinking about how to pass the reverse Turing test.

A lot of this talk is based on an essay called the The Dark Forest and Generative AI The Dark Forest and Generative AI

Proving you're a human on a web flooded with generative AI content I wrote back in January. So roughly 5 years ago in AI development time.

In it, I focused a lot on this question of how we might prove we’re human on a web filled with fairly sophisticated generated content and agents. I still think this is a relevant short-term concern.

The original Turing test had a human talk to a computer and another human through only text messages.

If the computer seemed plausibly human, it passed the test.

In the original, the computer is the one who has to prove competency.

On the new web, we’re the ones under scrutiny. Everyone is assumed to be a model until they can prove they’re human.

This is going to be challenging on a web flooded with sophisticated agents.

In the short term, we can employ a bunch of tricks like using unusual jargon and insider terminology that language models won’t know yet.

We can write in non-dominant languages that the models don’t have as much training data for, such as Welsh or Catalan (requires knowing one of these languages).

We can publish multi-modal work that covers both text and audio and video. This defence will probably only last another 6-12 months.

And lastly, we can push ourselves to do higher quality writing, research, and critical thinking. At the moment models still can’t do sophisticated long-form writing full of legitimate citations and original insights.

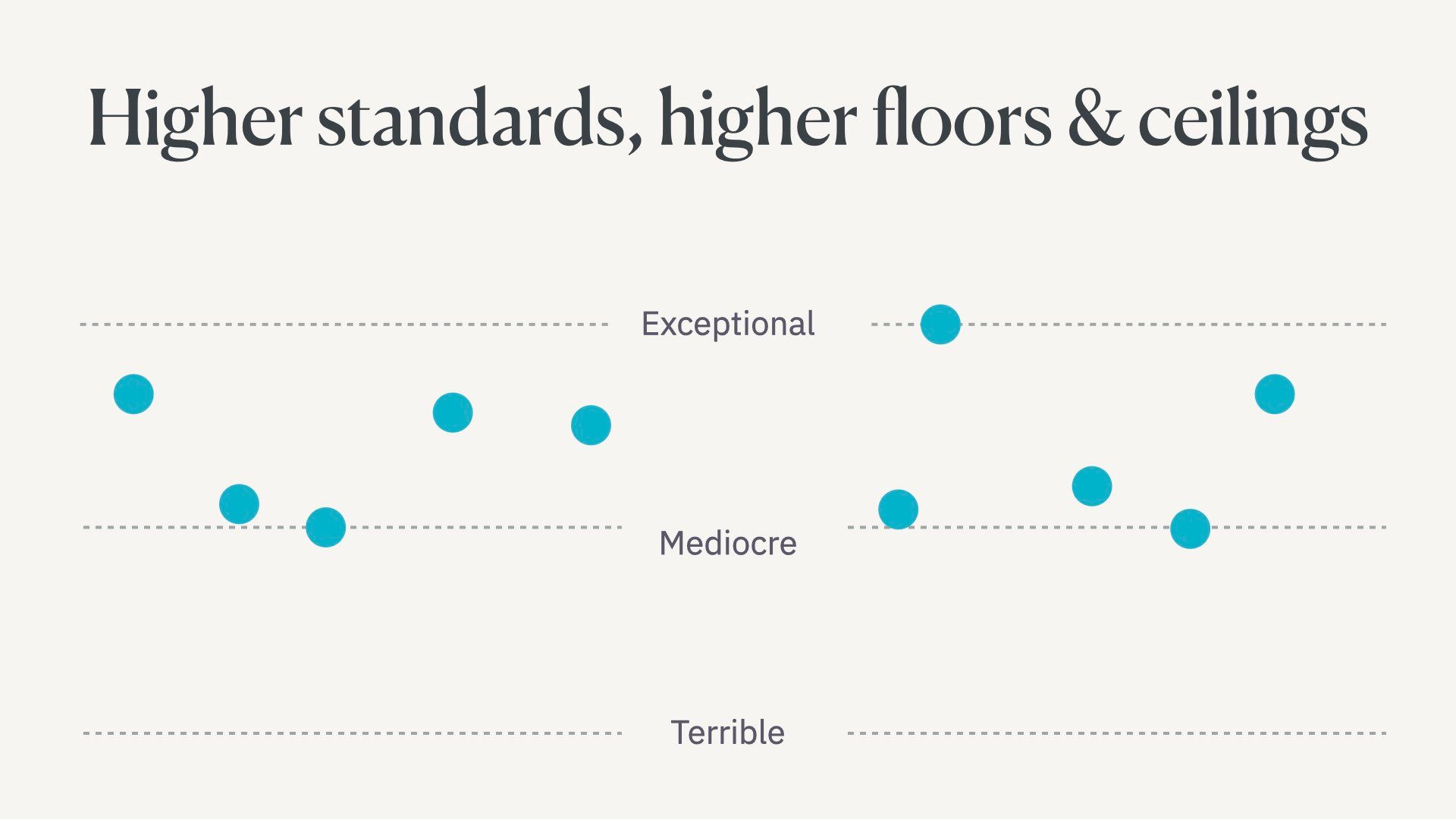

Related to this, I think we’re about to have much higher standard for humans. Models take over more mundane cognitive tasks and simpler writing.

We’ll demand more from human writers because great automated writing is cheap and prolific.

This raises both the floor and the ceiling for the quality of writing.

At the moment there’s some equal distribution of exceptional, mediocre, and terrible writers on the web.

Most of us are mediocre.

First, language models will raise the floor….

They’re useful for people who struggle to write because of their education level or because they’re writing in a second language.

These people’s work will improve.

Then I think there’s going to be some dual action for people with either mediocre or exceptional work.

Some of these people will become even more mediocre. They will try to outsource too much cognitive work to the language model and end up replacing their critical thinking and insights with boring, predictable work. Because that’s exactly the kind of writing language models are trained to do, by definition.

But some people will realise they shouldn’t be letting language models literally write words for them. Instead, they’ll strategically use them as part of their process to become even better writers.

They’ll integrate them by using them as sounding boards while developing ideas, research helpers, organisers, debate partners, and Socratic questioners.

These people will get even better. They’ll also be pushed to do much more original, creative work in a world flooded with generic content.

I apologise for this phrase, but it too perfectly captures the point I’m trying to make. I polled people on whether to use it and ended up with a 50/50 split. So I went for it.

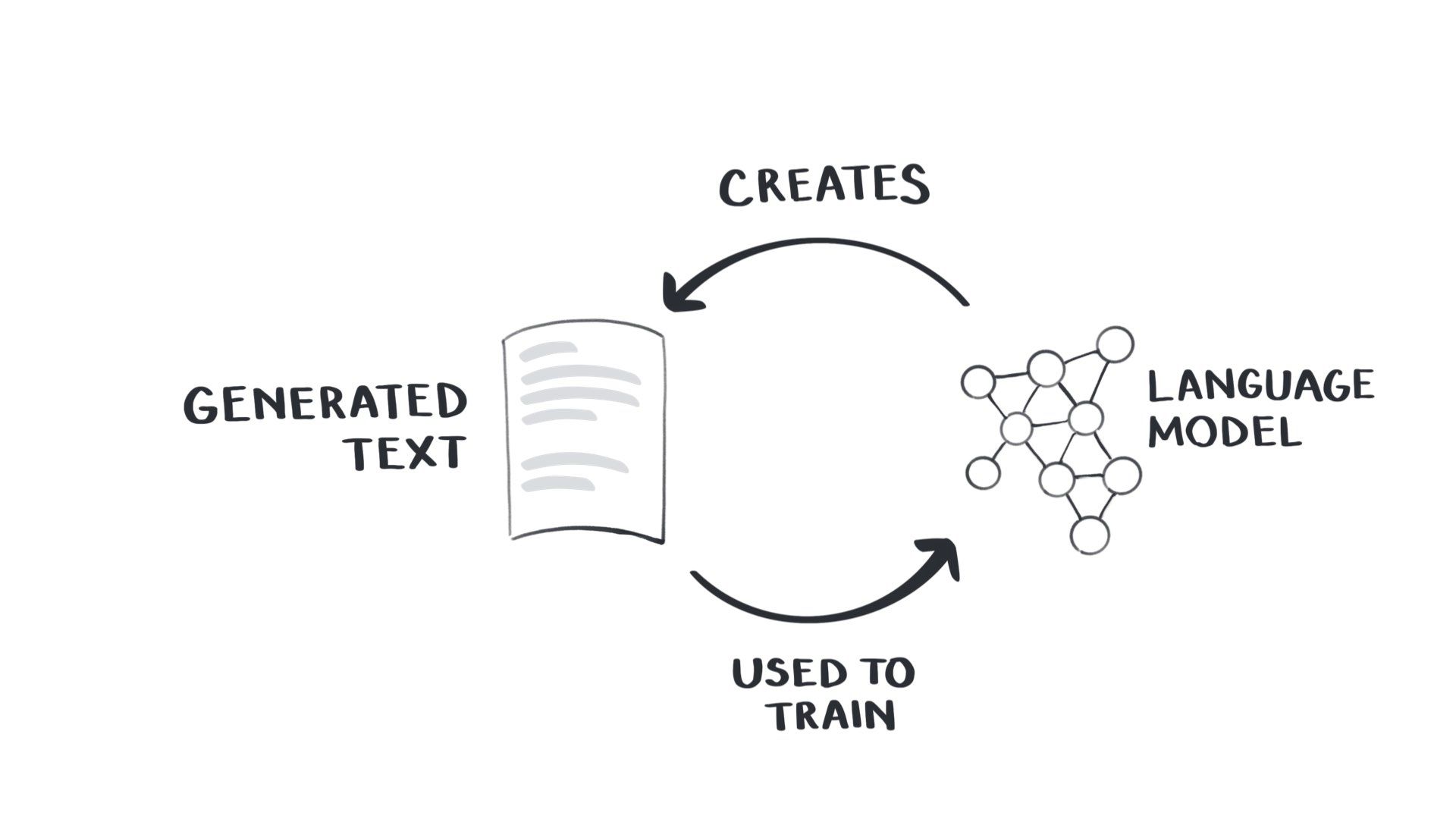

Anyway, we’re about to enter a phase of human centipede epistemology. Please don’t ask me to explain that, you can google it later.

The point is that if content generated from models becomes our source of truth, the way we know things is simply that a language model once said them. Then they’re forever captured in the circular flow of generated information.

So instead of our current model where the training data is at least based on real-world experience…

…we’re going to use the text generated by these models to train new models. That tenuous link to the real world becomes completely divorced from it

This is already happening – models are still being trained on text scraped from the web, and web text is increasingly being generated.

One tangible risk here is the development of scientific paper mills.

People may use generative models to write scientific papers that claim to find things that haven’t actually been tested. Usually, findings that benefit particular commercial or political interests.

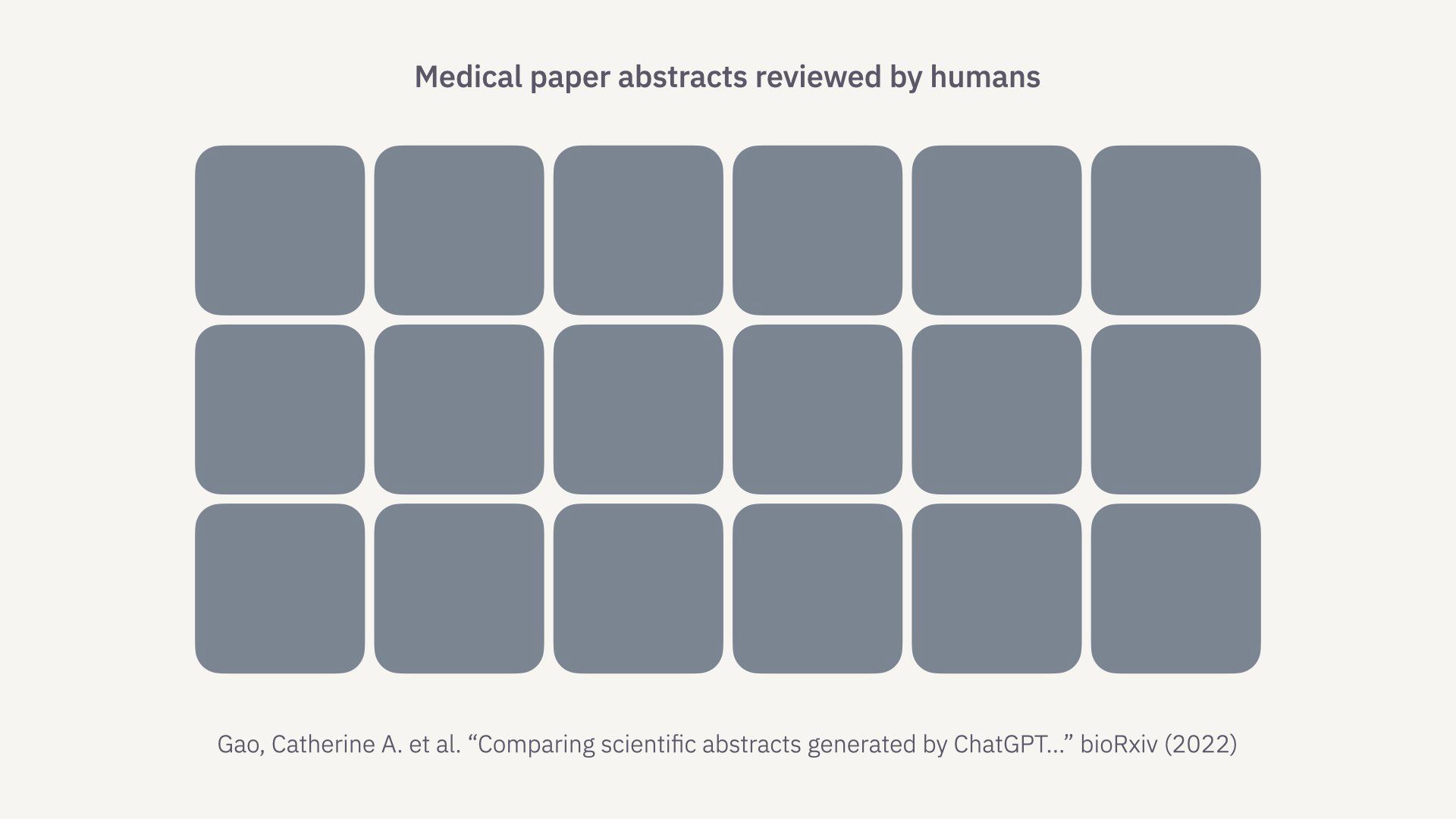

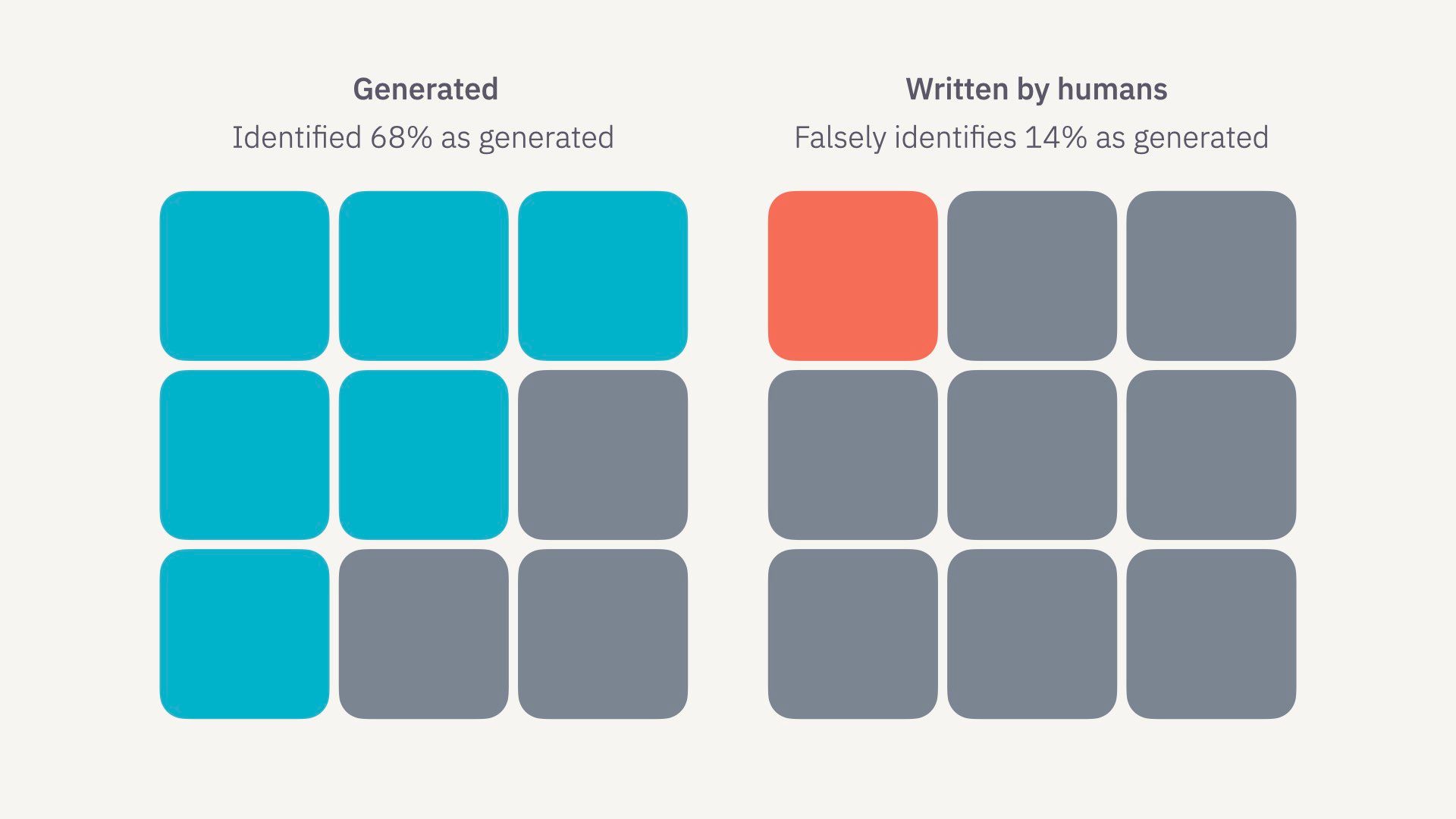

There was a study done this past December to get a sense of how possible this is: Comparing scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT to original abstracts using an artificial intelligence output detector, plagiarism detector, and blinded human reviewers” – Catherine Gao, et al. (2022)

Blinded human reviewers were given a mix of real paper abstracts and ChatGPT-generated abstracts for submission to 5 of the highest-impact medical journals.

The reviewers spotted the ChatGPT-generated abstracts 68% of the time. Which is pretty good! But they missed 32% of them. They also incorrectly identified 14% of real abstracts as being AI-generated.

We should note this was done with the GPT-3.5, which is less capable than the newer GPT-4, and didn’t use any sophisticated prompt chaining techniques.

So the stats are still in our favour, but we should expect this percentage to shift.

Takes the replication crisis to a whole new level.

Just because words are published in journals does not make them true.

Next, we have the meatspace premium.

We will begin to preference offline-first interactions. Or as I like to call them, meatspace interactions.

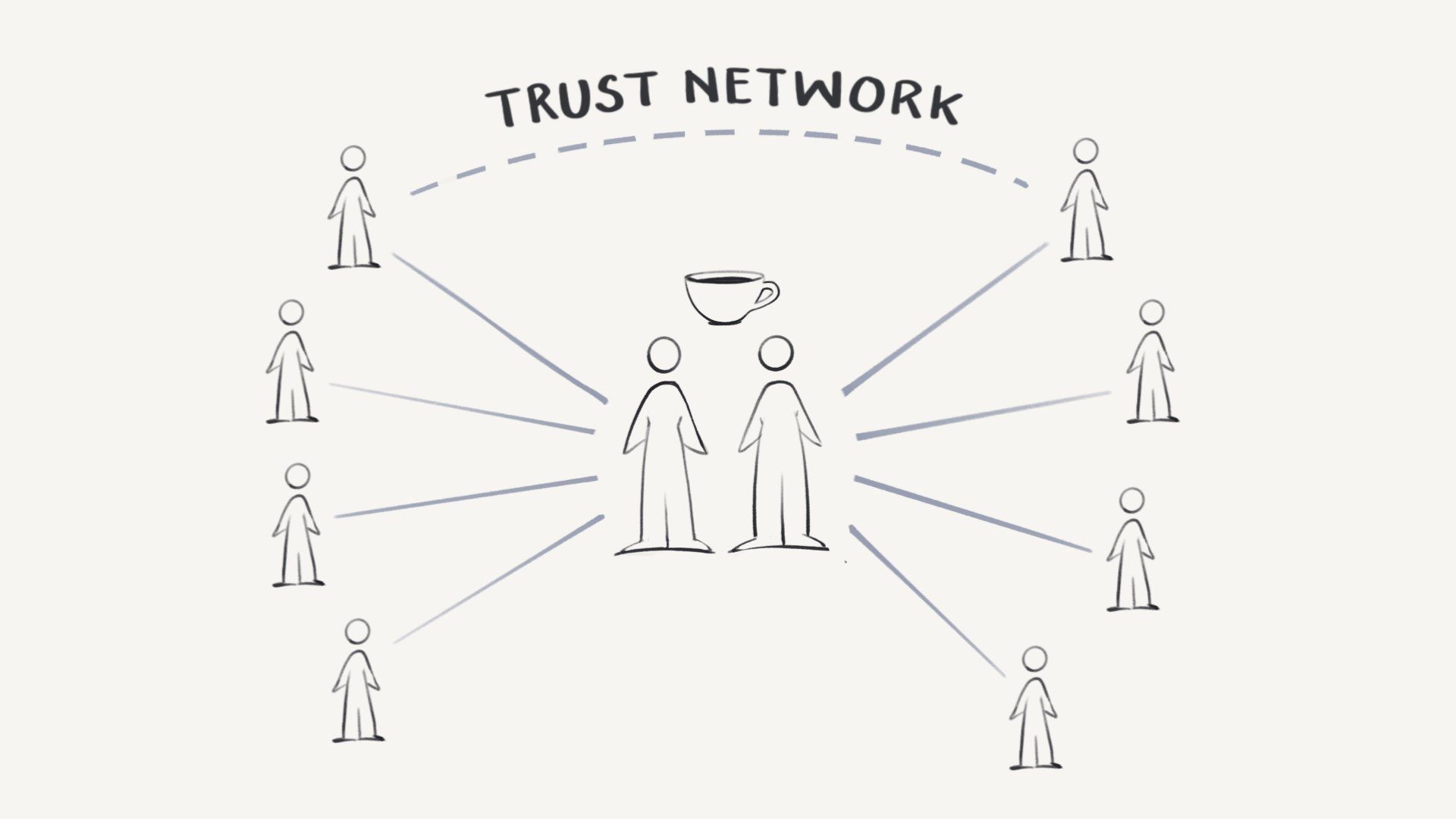

As we start to doubt all “people” online, the only way to confirm humanity is to meet offline over coffee or a drink.

Once two people, they can confirm the humanity of everyone else they’ve met IRL. Two people who know each of these people can confirm each other’s humanity because of this trust network.

This has a few knock-on effects: People will move back to cities and densely populated areas. In-person events will become preferable. Being in meatspace vs. cyberspace becomes a privilege and a premium.

This disadvantages people who can’t move to urban areas with higher populations, or are unable to regularly get out and meet other people. This includes people with disabilities, parents of young children, caregivers, or simply people without the material means to move to expensive cities.

This sadly undoes a lot of the connective, equalising power of the original web.

A natural follow-on from this is to put it on the blockchain! We could create on-chain authenticity checks for human-created content on the web.

This means some third party verifies your humanity in real life, then assigns you a cryptographic key to sign all your online content. Everything is then linked back to your identity. Clearly not great for anonymity or pseudo-anonymity.

I’m not a on-chain person so I don’t know the details of how this would work. I know people in this audience are more interested in this area and will have thoughts.

This is already a real project called Worldcoin

This scary-looking orb scans your eyeball and confirms your identity then created a unique human credential for you to use online.

Funnily enough, this project is affiliated with none other than OpenAI’s Sam Altman – he partially helped found it and is now on the board.

I’m expecting any day now Elon will announce the new purple check on Twitter that confirms your humanity

It’s only going to cost $30/month, and you don’t actually need to verify anything. You just check a box that says I’m human. Simple is better, right?

Those were all a bit negative but there is some hope in this future.

We can certainly fight fire with fire.

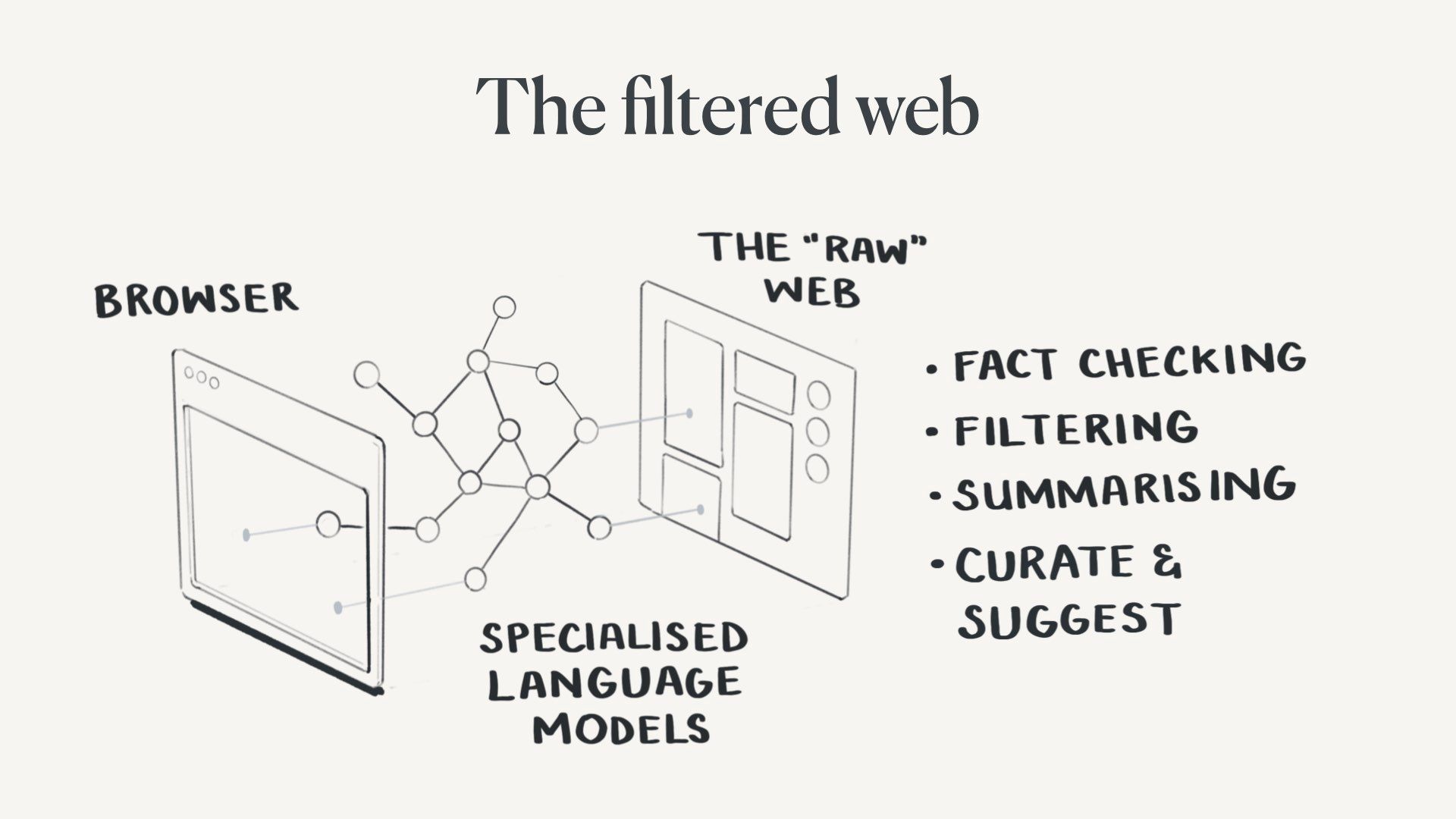

I think it’s reasonable to assume we’ll each have a set of personal language models helping us filter and manage information on the web.

I expect these to be baked into browsers or at the OS level.

These specialised models will help us identify generated content (if possible), debunk claims, flag misinformation, hunt down sources for us, curate and suggest content, and ideally solve our discovery and search problems.

We will have to design this very carefully, or it’ll give a whole new meaning to filter bubbles.

We will eventually find it absurd that anyone would browse the “raw web” without their personal model filtering it.

In the same way, very few of us would voluntarily browse the dark web. We’re quite sure we don’t want to know what’s on it.

The filtered web becomes the default.

The question I want everyone to leave with is which of these possible futures would you like to make happen? Or not make happen?

We have a lot of people sprinting to build fairly shallow interfaces on top of ChatGPT. The big companies are all scrambling to figure out their “AI play”. Their employees frantically DM me asking for advice about what to build.

At this point I should make clear generative AI is not the destructive force here. The way we’re choosing to deploy it in the world is. The product decisions that expand the dark forestness of the web are the problem.

So if you are working on a tool that enables people to churn out large volumes of text without fact-checking, reflection, and critical thinking. And then publish it to every platform in parallel… please god, stop.

So what should you be building instead?

I tried to come up with three snappy principles for building products with language models. I expect these to evolve over time, but this is my first pass

First, protect human agency. Second, treat models as reasoning engines, not sources of truth And third, augment cognitive abilities rather than replace them.

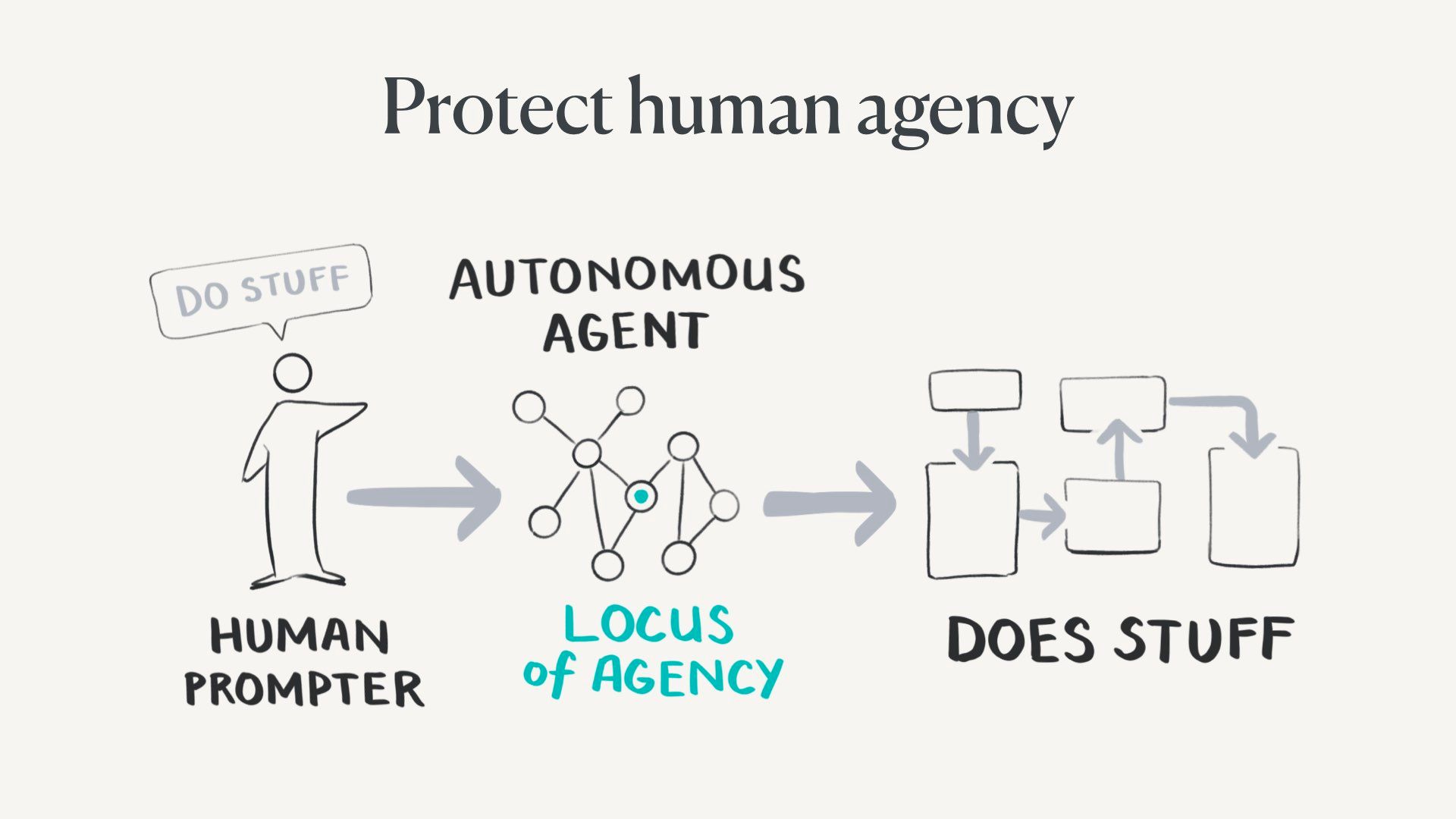

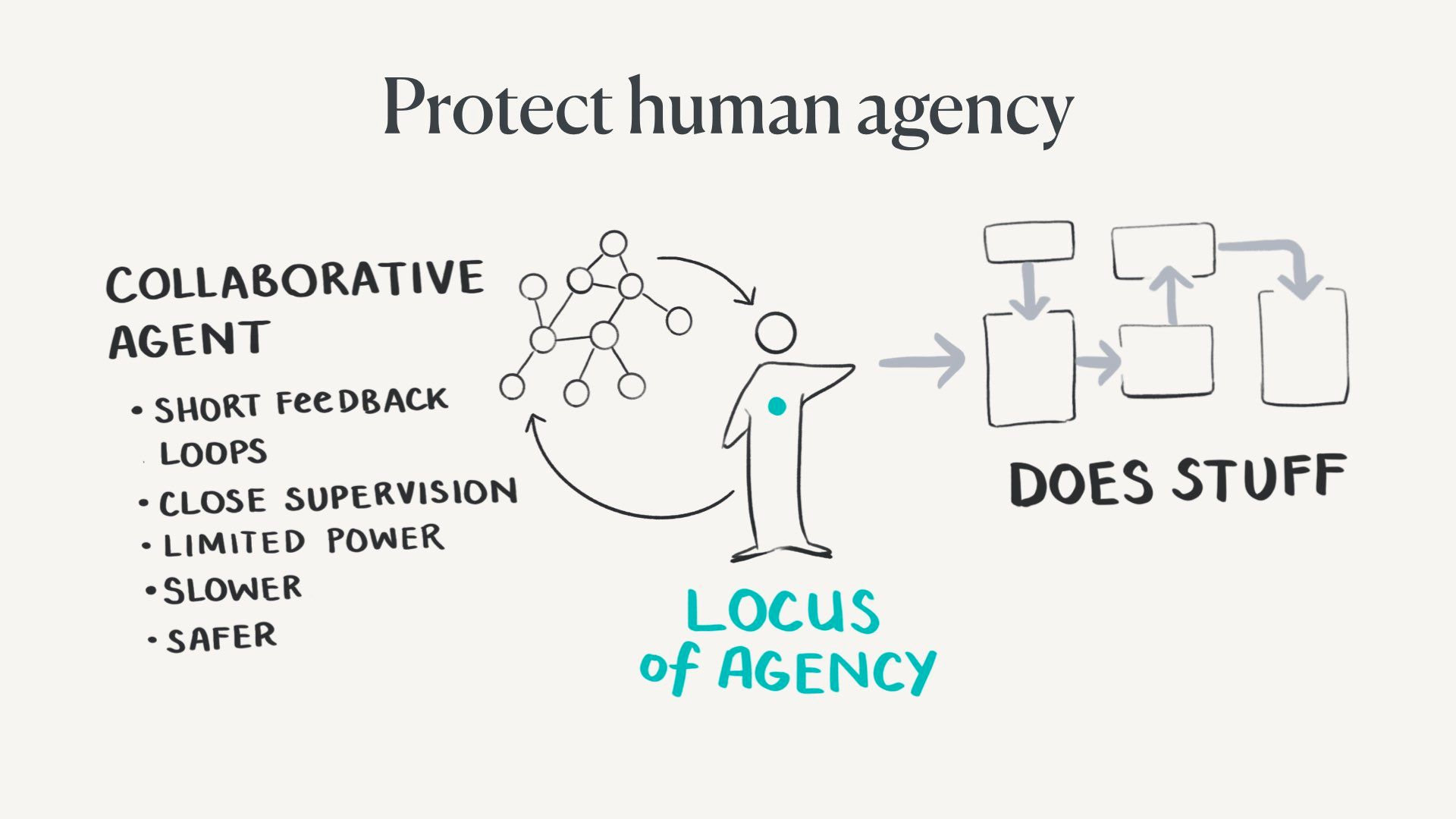

The generative agent architecture system starts with a human prompt, but then quickly hands off to autonomous agents to make decisions. The agent does a bunch of stuff, then reports back. The locus of agency in this system is within the agent.

And herein lies the path to self-destruction. This is what most AI safety researchers are very worried about – that we wholesale hand off complex tasks to agents who go off the rails.

A more ideal form of this is the human and the AI agent are collaborative partners doing things together. These are often called human-in-the-loop systems.

They have very short feedback loops. Humans can closely supervise system inputs and outputs, agents have limited power, and the locus of agency remains with the human.

These kinds of architectures will certainly be slower, so they’re not necessarily the default choice. They’ll be less convenient, but safer.

This is nice in theory, but who holds the agency in a system like this is opaque and sits on a spectrum. It’s not clear how much agency is too much to hand over at any one moment.

Geoffrey was just telling me yesterday there was a bunch of research done in the 90s on agency and interfaces we all need to read.

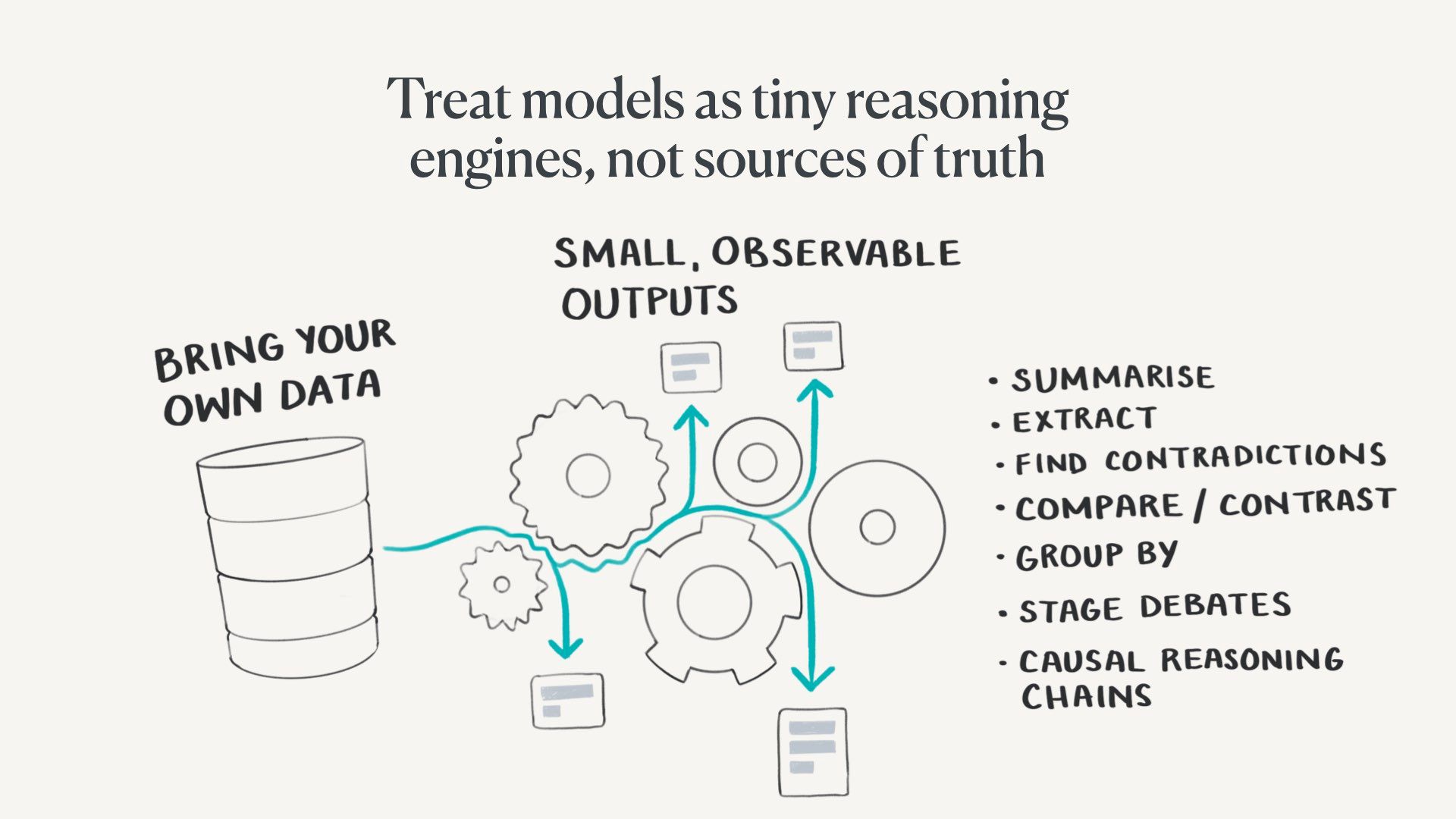

This ties into principle two: treat models as tiny reasoning engines, not sources of truth.

At the moment we tend to treat models as oracles. We ask them to answer questions or write things that become final outputs. This is where hallucination and detachment from reality become a problem.

Models are much more interesting as very small reasoning engines trained for specific, predictable tasks.

One alternate approach is to start with our own curated datasets we trust. These could be repositories of published scientific papers, our own personal notes, or public databases like Wikipedia.

We can then run many small specialised model tasks over them. We can do things like:

- Summarise

- Extract structured data

- Find contradictions

- Compare and contrast

- Group by different variables

- Stage a debate

- Surface causal reasoning chains

- Generate research questions

Some of these will pull on generalised training data, but there’s much less risk of wild hallucination in a scoped setting. We should also always have small, observable inputs and outputs we can check.

These outputs aren’t final, publishable material. They’re just interim artefacts in our thinking and research process.

Making these models smaller and more specialised would also allow us to run them on local devices instead of relying on access via large corporations.

Language models are actually quite good at these specific reasoning-like tasks. We use them a lot in Ought’s products.

This paper on “ Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence : Early experiments with GPT-4” out of Microsoft research a month ago shows that GPT-4 has more advanced general reasoning skills than previous models. To quote them…

“GPT-4 can solve novel and difficult tasks that span mathematics, coding, vision, medicine, law, psychology and more, without needing any special prompting”

They caveat it still made lots of mistakes and they’re not claiming its proto-AGI. But it can do things that seem like they would need some primitive reasoning skills.

This doesn’t mean it is reasoning – that’s a loaded and tricky word. We should still be sceptical and more research is needed, but it should make us rethink what models can be used for.

Lastly, we should be augmenting our cognitive abilities rather than trying to replace them.

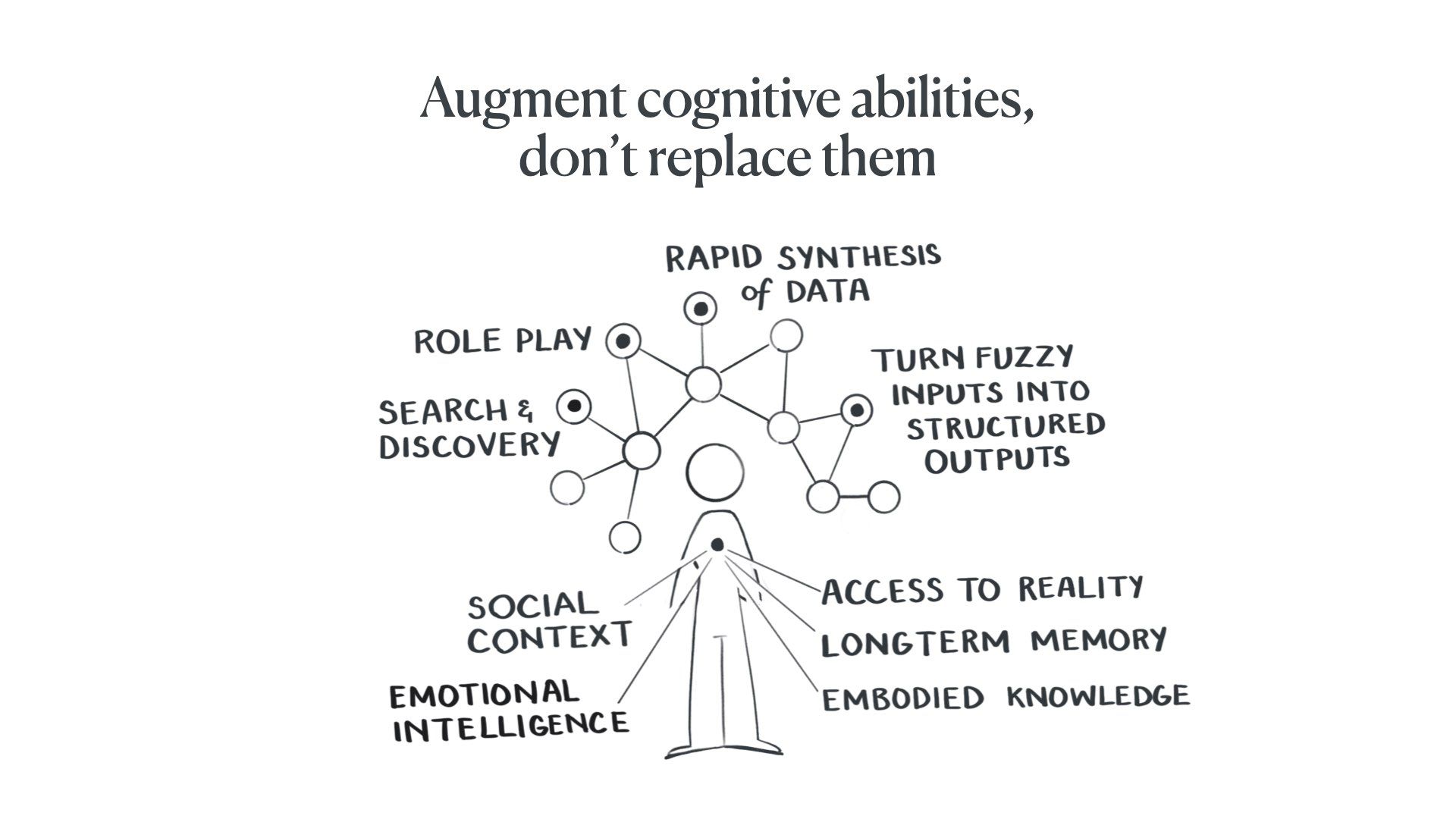

Language models are very good at some things humans are not good at, such as search and discovery, role-playing identities/characters, rapidly organising and synthesising huge amounts of data, and turning fuzzy natural language inputs into structured computational outputs.

And humans are good at many things models are bad at, such as checking claims against physical reality, long-term memory and coherence, embodied knowledge, understanding social contexts, and having emotional intelligence.

So we should use models to do things we can’t do, not things we’re quite good at and happy doing. We should leverage the best of both kinds of “minds.”

Talking about language models as alien minds that are very different to ours is a common metaphor in the industry. People often talk about how we’ve ‘discovered’ this new king of intelligence that we don’t yet understand.

Calling them aliens always makes me think of this. Which is maybe appropriate for AI risk.

But I at least like the metaphor of models being a new companion species we can work with. Kate Darling wrote a great book called The New Breed where she argues we should think of robots as animals – as a companion species who compliments our skills. I think this approach easily extends to language models.

We can best expand and augment our cognitive capacities by respecting their unique strengths and leveraging them.

There’s a good article called “ Cyborgism ” on this approach of blending human and AI capabilities – posted to LessWrong in February.

I don’t love LessWrong as a community but there’s occasionally some good work on there.

That’s all I have – thank you for listening!

I’m on Twitter @mappletons

I’m sure lots of people think I’ve said at least one utterly sacrilegious and misguided thing in this talk.

You can go try to main character me while Twitter is still a thing.