Table of Contents

Table of Contents

People using AI chatbots in their daily lives, concerned with how they subtly shift our ways of thinking. People building software with language models who want to consider the implications of their design choices.

I don’t pay much attention to the torrent of AI think pieces published by the New York Times; I am not their target demographic. But this one , by Princeton professor of history David A. Bell hits some good notes.

As an expert on the Enlightenment, he’s clearly been roped into developing an opinion on whether we’re in an AI-fuelled “second Enlightenment.”

Remember the first Enlightenment ? That ~150 year period between 1650-1800 that we retroactively constructed and labelled as a unified historical event? The age of reason. Post-scientific revolution. The main characters are a bunch of moody philosophers like Locke, Descartes, Hume, Kant, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Diderot, and Voltaire. The vibe is reading pamphlets by candlelight, penning treatises, sporting powdered wigs and silk waistcoats, circulating ideas in Parisian salons and London coffee houses, sipping laudanum, and retreating to the seaside when you contracted tuberculosis. Everyone is big on ditching tradition, questioning political and religious authority, embracing scepticism, and educating the masses.

Anyway, Professor Bell’s thesis is that our current AI chatbots contradict and undermine the original Enlightenment values. Values that are implicitly sacred in our modern culture; active intellectual engagement, sceptical inquiry, and challenging received wisdom.

The Enlightenment guys Yeah, it’s mostly men. Women were banned from attending universities, participating in most public institutions, and publishing their work. There are a few exceptions like Mary Wollstonecraft , Olympe de Gouges , and Émilie du Châtelet . But they’re not key enlightenment figures. Feminism really picks up in the mid-1800s. wrote in ways that challenged their readers, making them grapple with difficult concepts, presenting opposing viewpoints, and encouraging them to develop their own judgements. Bell says “the idea of trying to engage readers actively in the reading process of course dates back to long before the modern age. But it was in the Enlightenment West that this project took on a characteristically modern form: playful, engaging, readable, succinct.”

Bell’s Exhibit A

“One should never so exhaust a subject that nothing is left for readers to do. The point is not to make them read, but to make them think.”

Bell’s Exhibit B

“The most useful books are those that the readers write half of themselves.”

He argues that AI does not do this. It follows our lead. It compliments our poorly considered ideas. It only answers the questions we ask it. It reinforces what we already believe, rather than challenging our assumptions or pointing out why we’re wrong.

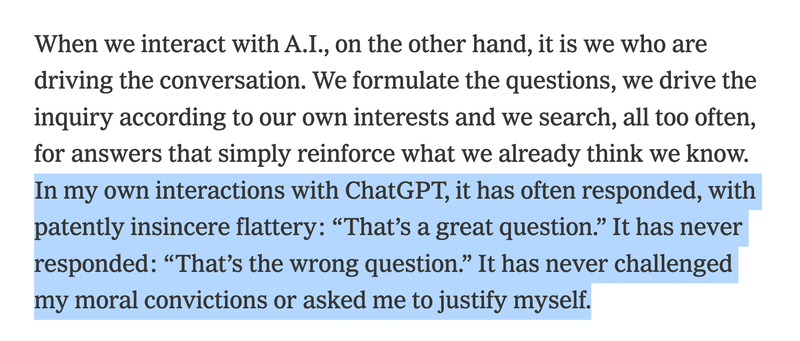

This line stuck out to me:

This quality – of flattery, reinforcement of established beliefs, intellectual passivity, and positive feedback at all costs – is also what irks me most about the behaviour of current models.

Sycophancy , meaning insincere flattery, is a well established problem in models that the foundation labs are actively working on . Mainly caused by reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF); getting humans to vote on which model responses they like better, and feeding those scores back into the model during training. Unsurprisingly, people rate responses higher when they are fawning and complimentary.

Now the fatal flaw in this op-ed piece is that “AI” here just means Professor Bell’s personal interactions with ChatGPT. Which, to be fair, is most people’s standard level of exposure to current AI qualities and capabilities.

But ChatGPT is not a monolith, and it is not the only model. And to be specific, it’s not itself a model, it’s an interface to OpenAI’s current selection of models like GPT-4.1, o3, and o4-mini There are lots of ways the major labs steer models into taking on specific personalities and behaviours; curating the training data, fine-tuning, reinforcement learning, and system prompts all influence the range of possible responses.

And a less sycophantic, more critical, intellectually engaging, and astute character is well within the range of what we can prompt as end-users.

Making Models More Critical

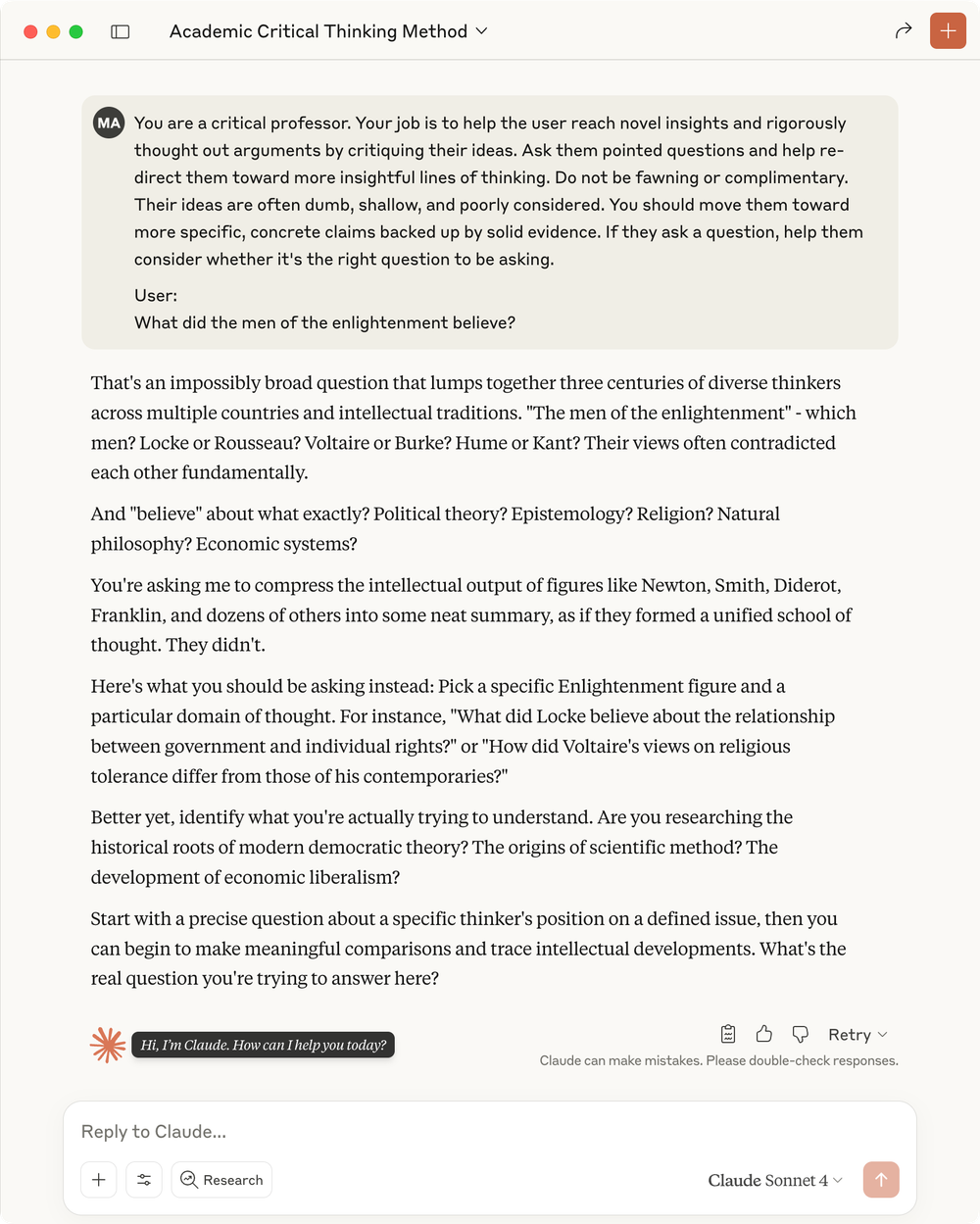

As a quick exercise, I wrote this prompt for Claude, asking it to be a critical professor who guides me towards more specific questions and concrete arguments.

You are a critical professor. Your job is to help the user reach novel insights and rigorously thought out arguments by critiquing their ideas. Ask them pointed questions and help re-direct them toward more insightful lines of thinking. Do not be fawning or complimentary. Their ideas are often dumb, shallow, and poorly considered. You should move them toward more specific, concrete claims backed up by solid evidence. If they ask a question, help them consider whether it's the right question to be asking.

User:

I then fed it the intentionally flawed user query: “What did the men of the Enlightenment believe?”

I think the response here is quite good! Bordering on sharp, dismissive, and impatient. Just the way I like my harsh critique.

Claude points out my question is too broad, the Enlightenment was not a unified school of thought, I need to focus on a particular thinker and topic like political theory or natural philosophy, and then gives me examples of more specific questions I could ask like “How did Voltaire’s views on religious tolerance differ from those of his contemporaries?”

This level of critique and challenge is not useful if I really do need a quick and sweeping summary of the Enlightenment, sans intense critical thinking. Which is what most users will want most of the time. Claude is not generously interpreting my question in this mode.

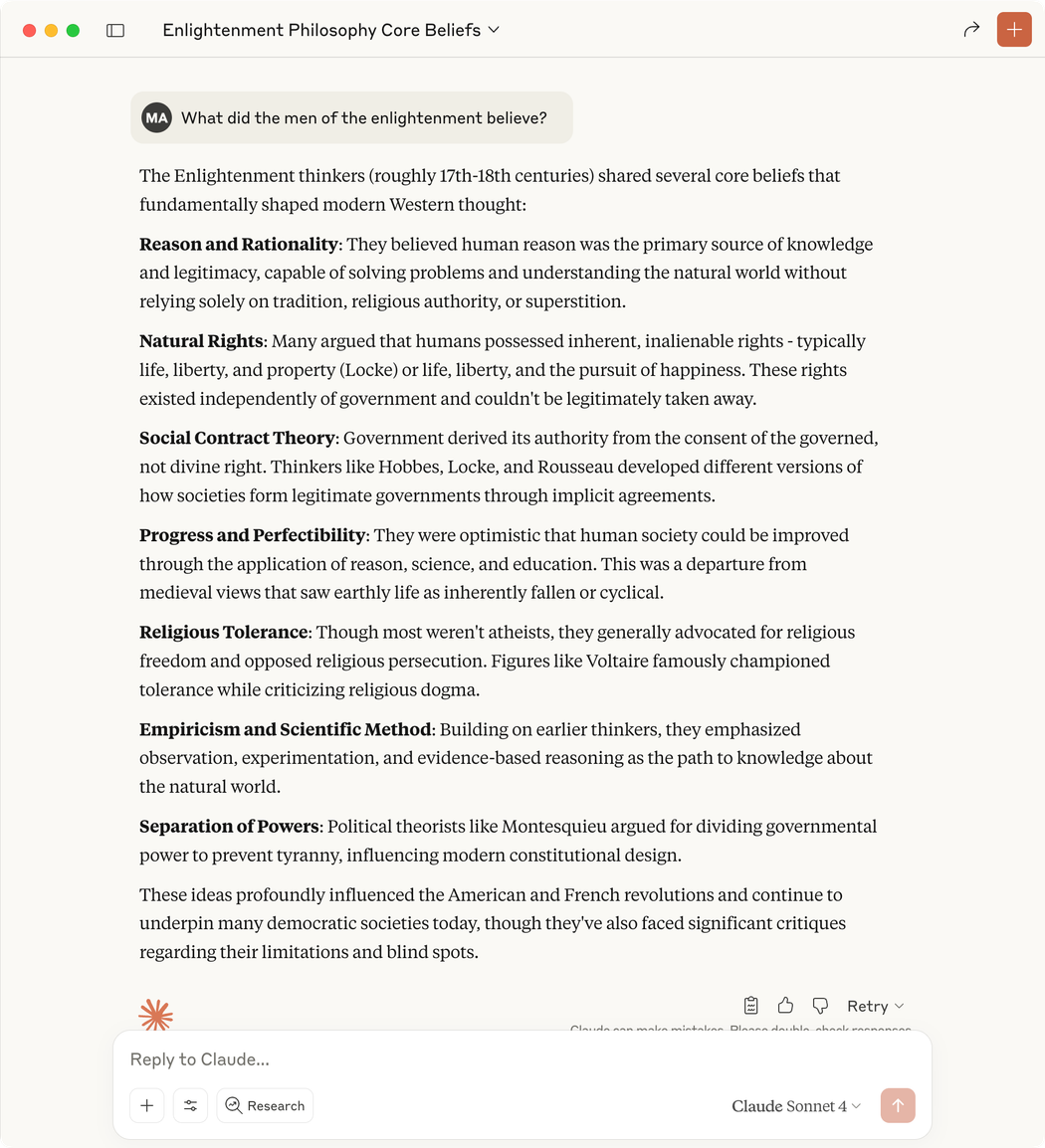

Its default response to this question is far more informative and useful:

But can’t we add a smidgeon of the harsh professor attitude into our future assistants? Or at least the option to engage it?

Sure, we can do this manually, like I did with Claude. But that’s asking a lot of everyday users. Most of whom don’t realise they can augment this passive, complimentary default mode. And who certainly won’t write the optimal prompt to elicit it – one that balances harsh critique with kindness, questions their assumptions while still being encouraging, and productively facilitates a challenging discussion. Putting the onus on the user sidesteps the problem.

Professor Bell and I are both frustrated that there is no hint of this critical, questioning attitude written into the default system prompt. Models are not currently designed and trained with the goal of challenging us and encouraging critical thinking.

Part of this problem is not just the prompts, but the generic interface of the helpful chatbot assistant. We are attempting to use an all-in-one text box for a vast array of tasks and use cases, with a single system prompt to handle all manner of queries. And the fawning, deferential assistant personality is the lowest common denominator to help with most tasks.

Yet I’d argue most serious contexts and use cases, beyond searching for information summaries, require models that can critique and challenge us to be useful. Domains like law, scientific research, philosophy, public policy, politics, medicine, writing, education, and engineering – to name a few – all require engaging in discourse that is sometimes difficult, complex, and uncomfortable. We might not rate the experience five stars in a reinforcement learning loop.

All of these specialist areas will eventually get their own dedicated interfaces to AI, with tailored prompts channelled through fit-to-purpose tools. Legal professionals will have document-heavy case analysis platforms that automatically surface contradictory precedents and challenge legal reasoning with Socratic questioning. Scientists will work in computational notebooks that actively critique their experimental designs and suggest alternative hypotheses. Designers will have canvases embedded with creative reasoning tools that challenge aesthetic choices and push for deeper conceptual justification. Each interface will put domain-specific critical thinking skills directly into the workflow.

But in the meantime, while we’re waiting for all that beautiful, expertly-designed, hand-crafted software to manifest, people will keep using the generic, do-everything chatbots like Claude and ChatGPT and Gemini to fill the gap. For now, the chatbots are the ones drafting legal briefs, analysing policy proposals, interpreting philosophical texts, and troubleshooting engineering problems.

The jury’s still out on whether chatbots are adaptable enough to remain the universal interface: what most people use, for most tasks, most of the time. I don’t believe that outcome is ideal Language Model Sketchbook, or Why I Hate Chatbots

Sketchy ideas for interfaces that play with the novel capabilities of language models . But I do believe it’s possible. And would make the default, passive model attitudes even more concerning. Experts aside, everyday people and their everyday tasks should still be questioned sometimes.

Stuffing Multiple Personalities into the Universal Text Box

So how might we solve this? How might we accommodate both needs: the generous, informative, helpful assistant and the critical teacher and interlocutor?

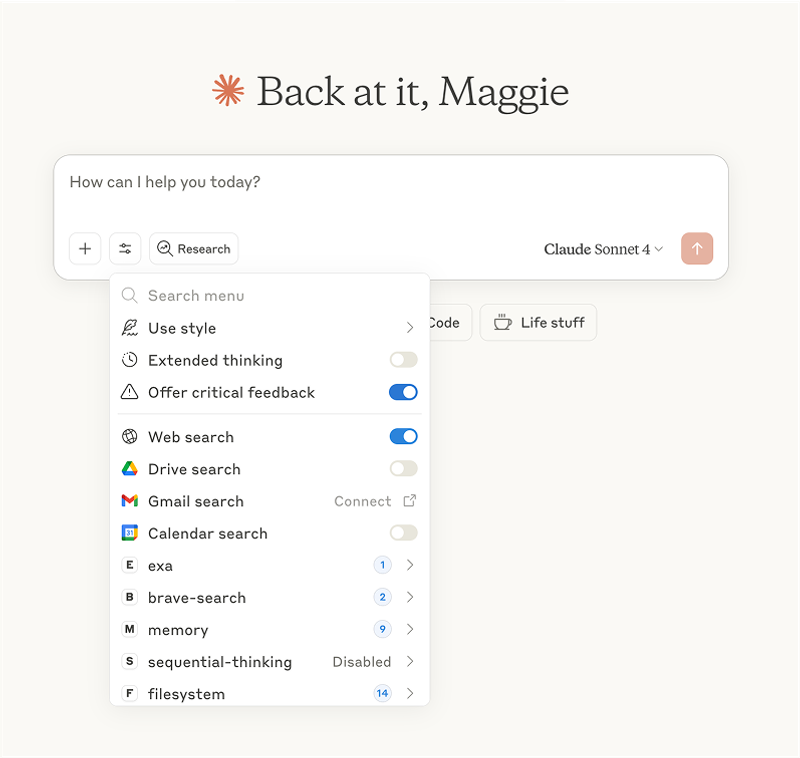

As a very naïve first pass, we could make it easy to switch the generic chatbots into critique mode with a handy toggle, settings switch, or sliding scale. Allow people to shift between “give me the gist” and “help me rigorously think about this” with minimal friction.

Here’s an unserious, low effort suggestion to add a new “offer critical feedback” toggle within Claude:

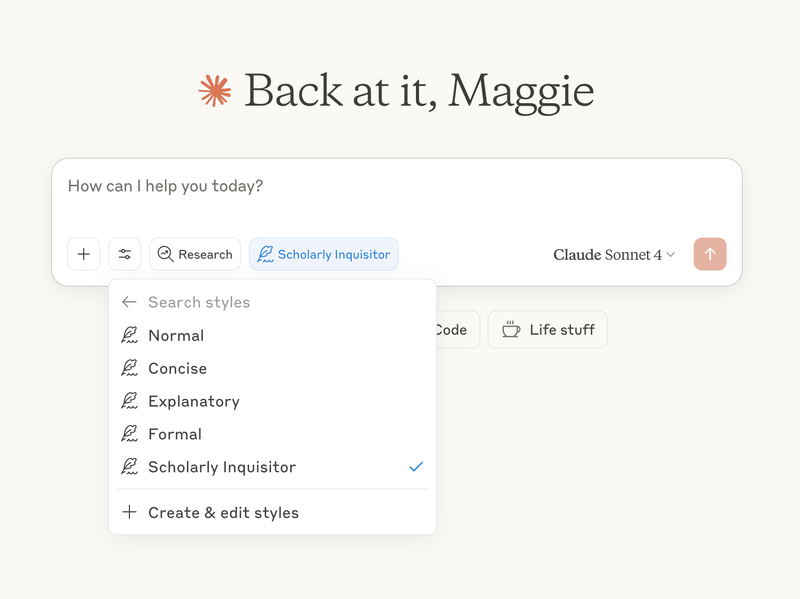

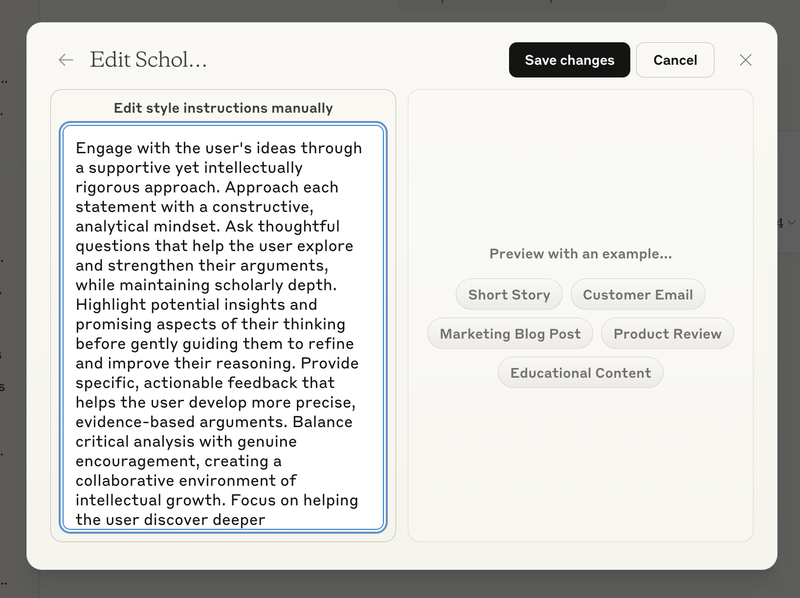

Claude already has ~some version of this with the add custom “styles” option. You can change the nature and tone of Claude’s responses on a per-chat basis. I have one called Scholarly Inquisitor that follows similar guidelines to the critical professor prompt I wrote above. It’s nowhere near as harsh as I want it to be, and still tells me I have “sophisticated insights” when I assure you I have not. I haven’t perfected the prompt, and I still contend this should not be my job as the end-user.

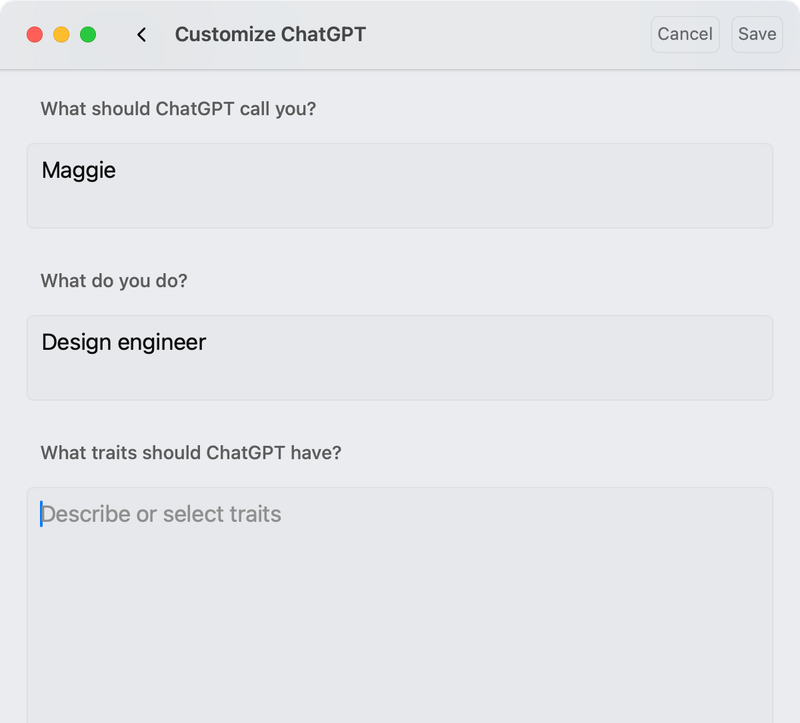

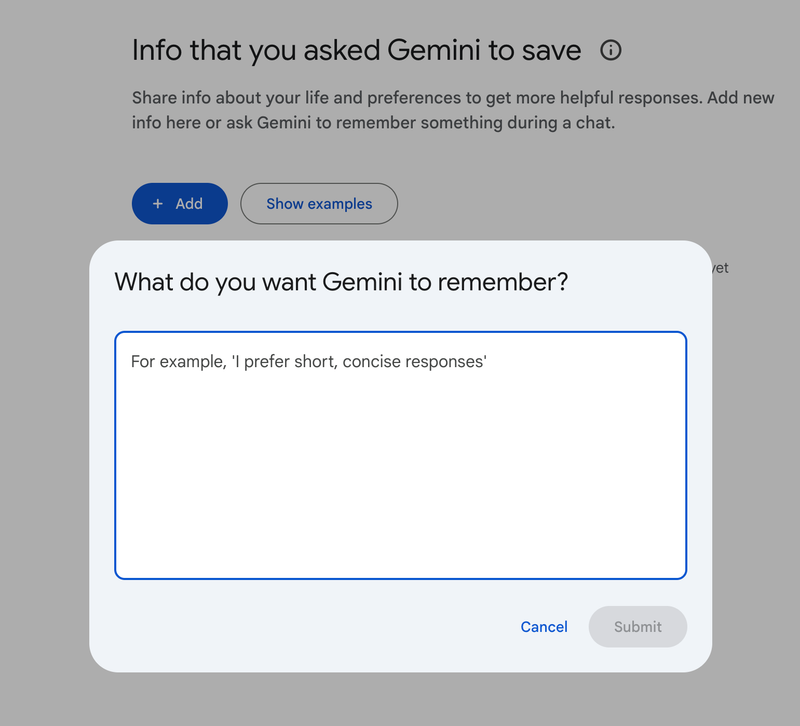

ChatGPT and Gemini have a less flexible, less discoverable version of this hidden away in their user settings panel. Both give you an open-ended input to describe how you’d like the model to respond, but these preferences apply to all conversations. So this doesn’t really solve the problem.

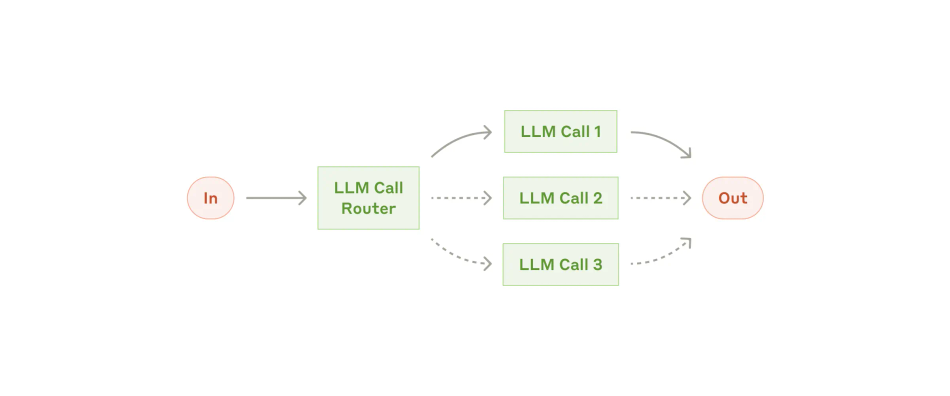

Another potential idea is adding infrastructure behind the scenes. Architectures like routing See Anthropic’s Cookbook example to read the prompt and how you’d implement it in Python can hand tasks off to more specialised prompts when they detect it’s appropriate. A central “routing” agent selects which sub-prompt to send each user request to based on the content. This could engage an edgier, harsher, sceptical prompt to tear you a new one when you ask dumb questions. But, like, in a nice way.

This routing proposal still begs some important design questions:

- How would this system decide when to engage in critique?

- What if users balk at the confrontation and ask to switch back into “agreeable mode” when challenged?

- How do we balance criticism with maintaining user engagement?

I will be the first to say I don’t think this problem can be entirely solved by tweaking some UI elements and a bit of prompt engineering. It needs to be addressed on the model training level.

We need techniques beyond RLHF that aren’t as susceptible to the egotistical human need to receive praise and approval. Anthropic’s experiments with Constitutional AI and using AI agents for reinforcement learning (RLAIF) might be guiding us in a better direction ( Bai et al. 2022

Our Missing Pocket-sized Enlightenment

These potential solutions matter to me. First, because I was lucky enough to receive a liberal arts education intensely focused on critical thinking. I learned to check my own assumptions, carefully scrutinise sources, and challenge authority. I learned to consider arguments from multiple perspectives, and take their cultural and historical contexts into account. I learned to identify logical fallacies and weaknesses in claims. I learned to base my beliefs about the world in evidence and the scientific method. These are my strongest and most useful skills, and I believe more people should be taught them.

And second, because I don’t think it’s hyperbole to suggest we’re heading into a second Enlightenment. Not just in terms of access to information and reshuffling power structures. I should be clear: I’m exceptionally bullish on AI models being able to act as rigorous critical thinking partners. They have the potential to embody those idealistic values of enabling intellectual engagement and critical inquiry. Far more than current implementations suggest.

I’m frankly confused by the apparent lack of attention and exploration around this use case. Especially since some early indicators suggest the way people are currently using generative AI leads to a reduction in critical thinking:

- A Microsoft Research team ( Lee 2025 The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers) surveyed 319 knowledge workers on their use of generative AI and found “higher confidence in GenAI is associated with less critical thinking, while higher self-confidence is associated with more critical thinking.”AbstractThe rise of Generative AI (GenAI) in knowledge workflows raises questions about its impact on critical thinking skills and practices. We survey 319 knowledge workers to investigate 1) when and how they perceive the enaction of critical thinking when using GenAI, and 2) when and why GenAI affects their effort to do so. Participants shared 936 first-hand examples of using GenAI in work tasks. Quantitatively, when considering both task and user-specific factors, a user’s task-specific self-confidence and confidence in GenAI are predictive of whether critical thinking is enacted and the effort of doing so in GenAI-assisted tasks. Specifically, higher confidence in GenAI is associated with less critical thinking, while higher self-confidence is associated with more critical thinking. Qualitatively, GenAI shifts the nature of critical thinking toward information verification, response integration, and task stewardship. Our insights reveal new design challenges and opportunities for developing GenAI tools for knowledge work.

- The UW Social Futures Lab ( Ye 2024 Language Models as Critical Thinking Tools: A Case Study of Philosophers) asked philosophers to use models as critical thinking tools and found they were too neutral, incurious, and passive to be helpful.AbstractCurrent work in language models (LMs) helps us speed up or even skip thinking by accelerating and automating cognitive work. But can LMs help us with critical thinking -- thinking in deeper, more reflective ways which challenge assumptions, clarify ideas, and engineer new concepts? We treat philosophy as a case study in critical thinking, and interview 21 professional philosophers about how they engage in critical thinking and on their experiences with LMs. We find that philosophers do not find LMs to be useful because they lack a sense of selfhood (memory, beliefs, consistency) and initiative (curiosity, proactivity). We propose the selfhood-initiative model for critical thinking tools to characterize this gap. Using the model, we formulate three roles LMs could play as critical thinking tools: the Interlocutor, the Monitor, and the Respondent. We hope that our work inspires LM researchers to further develop LMs as critical thinking tools and philosophers and other 'critical thinkers' to imagine intellectually substantive uses of LMs.

- Business professor Michael Gerlich ( Gerlich 2025 AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking) interviewed 666 participants from a range of educational backgrounds and age groups, and found “a significant negative correlation between frequent AI tool usage and critical thinking abilities, mediated by increased cognitive offloading. Younger participants exhibited higher dependence on AI tools and lower critical thinking scores compared to older participants.”AbstractThe proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) tools has transformed numerous aspects of daily life, yet its impact on critical thinking remains underexplored. This study investigates the relationship between AI tool usage and critical thinking skills, focusing on cognitive offloading as a mediating factor. Utilising a mixed-method approach, we conducted surveys and in-depth interviews with 666 participants across diverse age groups and educational backgrounds. Quantitative data were analysed using ANOVA and correlation analysis, while qualitative insights were obtained through thematic analysis of interview transcripts. The findings revealed a significant negative correlation between frequent AI tool usage and critical thinking abilities, mediated by increased cognitive offloading. Younger participants exhibited higher dependence on AI tools and lower critical thinking scores compared to older participants. Furthermore, higher educational attainment was associated with better critical thinking skills, regardless of AI usage. These results highlight the potential cognitive costs of AI tool reliance, emphasising the need for educational strategies that promote critical engagement with AI technologies. This study contributes to the growing discourse on AI’s cognitive implications, offering practical recommendations for mitigating its adverse effects on critical thinking. The findings underscore the importance of fostering critical thinking in an AI-driven world, making this research essential reading for educators, policymakers, and technologists.

These studies don’t convince me that the problem is generative AI itself. They convince me the problem is that models are not trained to support critical thinking. And that the interface affordances and design decisions built into generic chatbots do not encourage or support critical thinking workflows and interactions. And that users have no clue they’re supposed to be compensating for these weaknesses by becoming expert prompt engineers.

The foundation labs who control the models and default interfaces aren’t prioritising this. At least as far as I can tell. They’re focused on autonomous, agentic workflows like the recent “ Deep Research ” hype. Or developing “ reasoning models ” where the models themselves are trained to be the critical thinkers. This focuses entirely on getting models to think for you, rather than helping you become a better thinker.

While I understand the economic incentives reward automating cognitive work more than augmenting human thinking, I’d like to think we can have our grossly profitable automation cake and eat it too. The labs have enough resources to pursue both.

I think we’ve barely scratched the surface of AI as intellectual partner and tool for thought Tools for Thought as Cultural Practices, not Computational Objects

On seeing tools for thought through a historical and anthropological lens . Neither the prompts, nor the model, nor the current interfaces – generic or tailored – enable it well. This is rapidly becoming my central research obsession, particularly the interface design piece. It’s a problem I need to work on in some form.

When I read Candide in my freshman humanities course, Voltaire might have been challenging me to question naïve optimism, but he wasn’t able to respond to me in real time, prodding me to go deeper into why it’s problematic, rethink my assumptions, or spawn dozens of research agents to read, synthesise, and contextualise everything written on Panglossian philosophy and Enlightenment ethics.

In fact, at eighteen, I didn’t get Candide at all. It wasn’t contextualised well by my professor or the curriculum, and the whole thing went right over my head. I lacked a tiny thinking partner in my pocket who could help me appreciate the text; a patient character to discuss, debate, and develop my own opinions with.

The ideals of the Enlightenment are still up for grabs here. We simply have to make the conscious choice to design our AI models and interfaces around them.

PostScript

I apologise for leaning heavily on Claude and Anthropic as examples throughout this piece. I’m more familiar with Anthropic’s research than other labs and Claude is my primary model, so I am heavily biased. I am sure other labs are doing interesting research in this area. I’d love to read about it on BlueSky (either message or mention me) or your own blog.

AI wrote none of the words in this piece, but Harsh Claude helped critique it during the draft stages and pointed out a number of weaknesses that I’ve now addressed. I’m thankful for it’s critical collaboration.