Anyone suffering from vestibular neuritis, labyrinthis, or other vestibular issues looking for some reassurance and points of comparion. Or anyone with a normal balance system curious what it’s like to spend months unable to see, walk, or talk straight, and wants to read an account of my unhinged hypochondria.

At around 2pm on January 23rd, while on a work trip to San Francisco, jet-lagged, staring into a screen, and trying to organise a chaotic Figma file, my brain began to malfunction. My eyes refused to focus on the shapes in front of me and my head felt like it was floating away from my body.

Alarmed, I thought I must be dehydrated or in a dire blood sugar crash, and headed towards the kitchen of our little co-working space. Mid-way down the corridor I fell into the wall. Or rather, veered into the wall as the floor began to spin above my head. Panicking, I ducked into the bathroom, and only remember staring at myself in the mirror, clutching the sink, and thinking I was utterly losing my mind. This must be a stroke. Or a heart attack. Or sepsis.

I had completely lost my sense of balance. In waves of disorientation, the room was spinning around me. To simulate the sensation, imagine being on a violent version of the teacup ride at Disneyland. Where the scene in front of you whips away so fast, your brain doesn’t have time to register anything in it. Your eyes flit around for solid ground, unable to tell how far away walls or objects are, nausea builds in the back of your throat, and your stomach threatens to empty itself.

Except you’re standing completely still in an empty womens bathroom, wondering if you’re dying.

I stood anchored to that sink for a long time, afraid that letting go might fling me off the earth. Over something like fifteen minutes, the spinning began to ease off. I gingerly palmed my way to the wall, doorframe, along the corridor, and back to the office to sit down and try to strategise what to do, while still trying not to throw up or melt down into a pile of panic. Even with my eyes closed the room twirled around me. One of my co-workers came over to ask a question, noticed my strange state of disarray, and helped me find the nearest urgent care clinic.

By the time I made it to the clinic and saw a doctor an hour later, the spinning had slowed to a more manageable lightheadedness and off-kilter feeling. They did a suite of tests that all came back normal, declared I wasn’t dying, and sent me off with a diagnosis of “vertigo,” possibly caused by BPPV: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo . In other words, a set of small calcium crystals inside my ears that regulate my sense of up and down may have become dislodged, and were floating free in places they shouldn’t be.

Relieved to hear the word “benign” in the diagnosis, and reassured I wasn’t in any grave danger, I tried to shake it off and boarded my flight back home to London. I spent the following days sleeping and recovering among the creature comforts of home. The dizziness dissipated and within a week I was barely feeling it. Problem solved! I figured it was a blip in the matrix I no longer had to worry about.

Except the blip came back a few days later. Not as dramatically this time. But consistently. I awoke every morning and within minutes noticed my head was slightly floaty, as if rocking back and forth in space. Moving around sped it up to a twirl. I had to lean against walls to stay upright. Walking took exceptional concentration, and happened at a snail’s pace. Going outside onto the street was visually overwhelming, and I stumbled about like someone six beers deep. It felt like watching a film with three-quarters of the frames skipped; I couldn’t accurately sense how far my body was from the ground, objects, or people around me. The contradictory signals travelling from my eyes and body to my brain left me perpetually seasick and on the verge of vomiting.

Certain things made it worse; turning my head too quickly, bending down, standing up too fast, bright lights, screens, scrolling on websites, fast moving objects like cars passing by, complex scenes like busy streets, being on trains or buses. Frankly, doing anything but lying down with my eyes closed seemed like a bad idea.

This went on for weeks. Some days were worse than others, but no days were free and clear. I began my tour of various doctors, all with different theories on what was happening. The first did some blood tests, saw nothing out of the ordinary, and declared there was nothing wrong with me and I didn’t need a follow up appointment (love that guy).

The second was more concerned, asked many questions, had me touch my fingers to my nose a lot, and tested me for BPPV (misaligned ear crystals) by watching how my eyes moved when she tilted my head. I tested negative. This only made me anxious that something more nefarious was going on. If you google “causes of vertigo, dizziness, and nausea,” of course you hit the worst-case-scenario jackpot: brain tumour. Fantastic. Doctor two eventually declared she was “stumped”, prescribed me anti-nausea meds, and said we should just wait a few weeks to see if it would go away.

At this point I was in full-on “I’m dying of a brain tumour” mode and not keen on waiting it out. Brain fog had set in; I had trouble concentrating and finding the right words in conversations. I mispronounced things and began sentences I couldn’t quite find the ends of. My neck became extremely stiff and sore. I began to have weird pains, pressure, and constriction sensations at the back of my head. The web suggested these might be tension headaches (another common symptom of brain tumours – very reassuring).

I booked an appointment with an ENT Ear, nose, and throat specialist. Also known more poetically as an otorhinolaryngologist. at a private clinic, willing to pay any amount for someone to ground my worries in reality. I’m very lucky to have medical insurance which covered this, but it was initially unclear how much outpatient treatment they would pay for, so I was prepared to eat the cost myself. Doctor three (my favourite) had me do lots of strange coordination and balance tests, ruled out various possibilties, and finally declared he was “80% sure” it was vestibular neuritis . This is almost the same thing as labyrinthitis , but without the hearing loss or tinnitus.

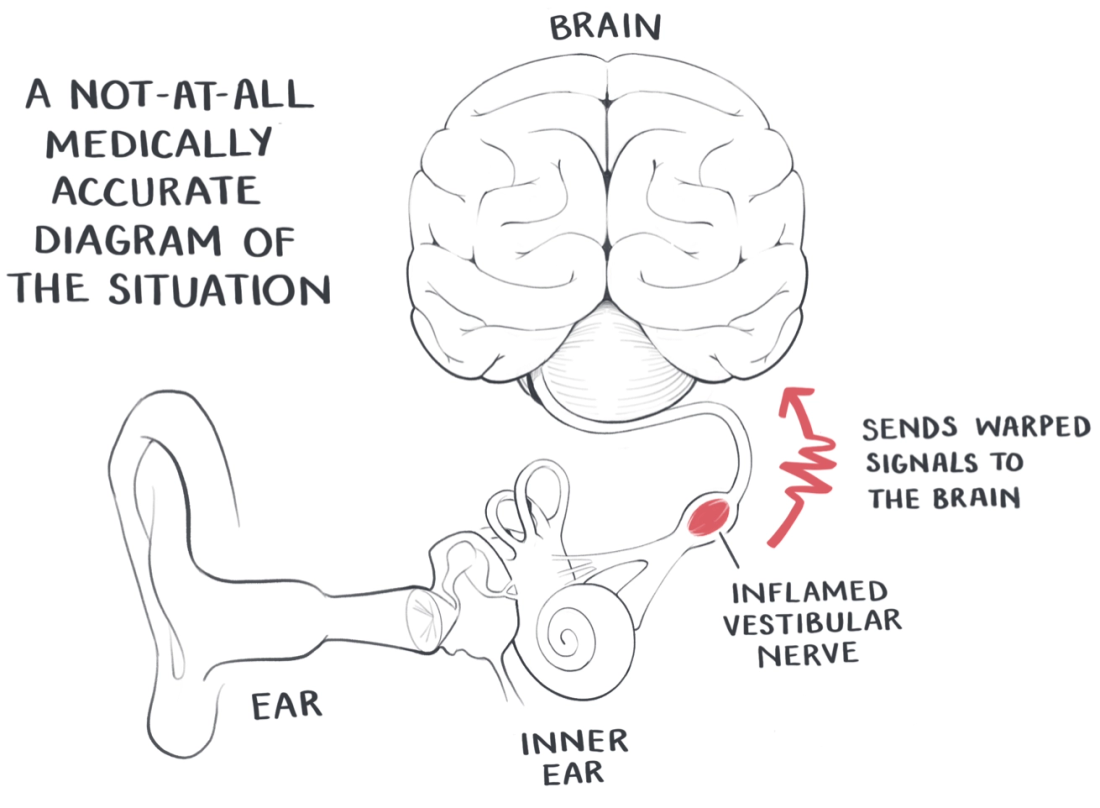

80% of the dread left my body. I’d read plenty about vestibular neuritis by that point, having let my hypochondriac side run wild on the web. It’s an infection of the vestibular nerve that connects the balance system in your inner ear to your brain. The infection damages the nerve, which then sends warped and incorrect signals about your position in space to your brain.

This diagnosis seemed great! But it still felt a bit tentative. Vestibular neuritis is usually preceded by a respiratory or ear infection, and I’d had neither before my episode of vertigo back in January. I didn’t love the 20% chance it was something else, so asked for an MRI (or rather, said I was willing to pay an extortionate amount for an MRI to avoid lying wide awake at 5am, imagining the giant mass growing in my cerebellum). Thankfully it came up clean. No tumours. No bleeding. No lesions. God bless my extremely normal brain.

As I write this, eight weeks in, I’m not yet recovered. My head currently feels like it’s doing a gentle spin in my unmoving body. I’ve been looking at a screen for about two hours, which means I’m pretty nauseous, but that’s par for the course these days. On the bright side, my symptoms have faded enough for me resume normal life; I can walk in a straight line, grocery shop, go for runs, meet friends for coffee, and work on screens all day. I’m just dizzy the whole time.

Even in my disoriented state, I’m profoundly relieved and happy. While this might sound like a warped recipe for joy, try spending weeks believing you’re about to discover you have a tragic and fatal diagnosis, then all at once being freed from it. To be fair, this was a cage of my own making. More sensible people don’t google every last symptom, and fixate on the dire ones. Let’s just say I have a strong survival instinct.

I’m deeply grateful to the dozens of people who have written accounts or made YouTube videos about their vestibular diseases. There are many besides vestibular neuritis that have very similar symptoms and prognoses; BPPV, labyrinthitis, vestibular migrane, PPPD, and Ménière’s disease. Without them I would still be in a wild panic. The lightweight medical material available on the web claims most people recover within a few weeks, and mention nothing about concurrent symptoms like brain fog, light sensitivity, stiff necks, or head pains and pressure. Many of the cursory, sterile medical descriptions of what vestibular issues feel like didn’t match my lived reality, which sent me into a spiral of imagining something more sinister was causing this.

Hearing real people describe their symptoms in long forum posts and diary-style vlogs reassured and informed me far more than any doctors did. It helped me adjust my expectations of how long recovery could take. Others suffer more severe symptoms for months, or even years. Once the vestibular nerve is permanently damaged, the brain has to relearn how to process visual and bodily sensations of where you are in space. The warped signals coming in from your ears are unfamiliar, and it figures out ways to cope by relying more on vision and proprioception. This is impressive! Neuroplasticity in action.

Most people said their quality of life improved once they recieved vestibular rehabilitation therapy which involves specific exercises tailored to retrain your brain. I’m currently waiting on a referral for this. Overall, recovery rates are great; everyone relearns how to balance eventually, you just feel a bit wobbly every now and again. The medical literature doesn’t have many exact numbers on recovery time, other than “weeks to years,” but one study showed the majority of improvements happen by week ten, and then it becomes a management and coping game.

I hope someone disoriented, scared, and harbouring their own statistically unlikely brain tumour self-diagnosis finds this as they frantically Google their distressing symptoms. Take a deep breath. Find yourself a good ENT. It’ll all be okay.