Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Pregnant people, partners of pregnant people, people who expect to become pregnant at some point, and anyone curious about the experience of growing another human inside of you.

I’m currently growing a human – my first. Having never grown a human before, and spent very little time around other people growing humans, the past six months have been a constant parade of surprises. This is a smörgåsbord of reflections on my first 30+ weeks of pregnancy, from holding space for potential loss, to our strange obsession with comparing babies to an escalating array of fruits, to the barrage of social media mumfluencers demanding we maximise “naturalness” in pregnancy and parenting (despite that being an impossibly vague and misleading concept), to how recent medical and political advancements have made my pregnancy far less stressful and fraught than my mother’s or grandmothers’.

Living with Schrödinger’s Baby

For the first few months of being pregnant, you have to assume you are both pregnant and not pregnant. You would think this would be more clear cut. Surely pregnant means pregnant? Apparently not.

There’s a relatively high chance of miscarriage within the first 12 weeks of a pregnancy. Most

actually happen before the 7th week (95% in Tong 2008

For the nervous among us who like to seek comfort in statistics, this pregnancy loss calculator comes in handy.

Once you’re past the 12 week mark, you may officially have a baby, but you don’t necessarily have a healthy and functioning baby. For that you have to wait until the 20 week mark when you get a full anatomy scan and learn that all of baby’s limbs and organs are in good working order.

I began to refer to this whole situation as being pregnant with Schrödinger’s baby. You both have a baby and do not have a baby. You have to make plans that assume there will be a baby in your life within the next 4-6 months – such as telling work, figuring out where a crib might go, making a budget, strategising childcare, and begin researching how to keep a baby alive – but simultaneously not get too emotionally attached to the idea of actually having a baby.

This pretending to not-be-entirely-pregnant is made complex by the fact you first go through the potentially debilitating experience of all-day-all-the-time ”morning” sickness at the start of this period, and become visibly pregnant towards the end of it. This is a good exercise in holding two contradictory truths in your mind at once. A bit like a zen koan .

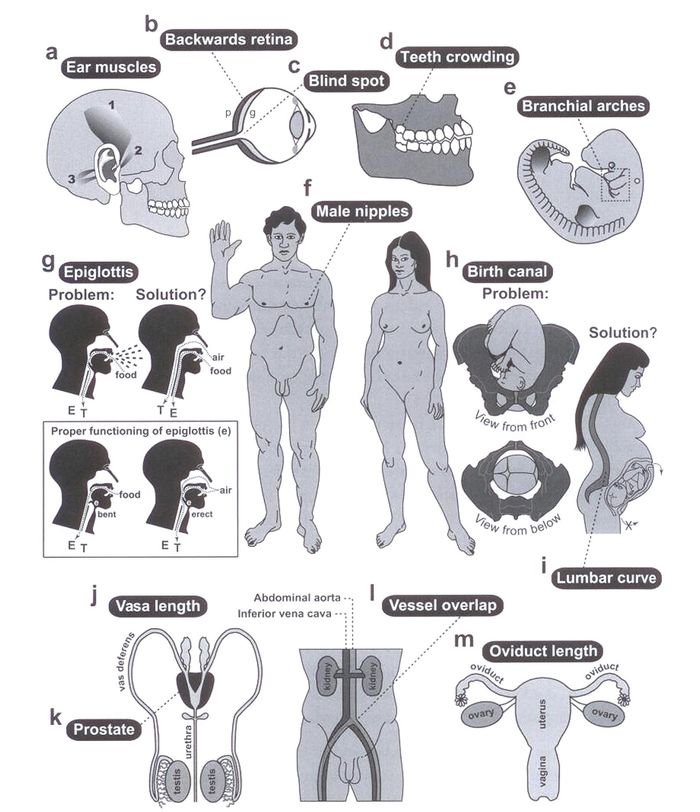

Evolution Is Indifferent to Your Suffering

Before pregnancy, I had some fuzzy, semi-spiritual belief that the long and magical process of evolution was on my side and always served my best interests. Even if our bodies have their quirks , they’ve been molded by millions of years of evolution to keep us alive and thriving in earthly environments.

But “alive”, doesn’t mean happy, comfortable, or feeling like you’re bathed in warm light. Evolution is perfectly fine with you feeling like you’ve been sucked into a dark, joyless black hole of nausea and fatigue – as long as you’re alive while there. As long as you reproduce and the offspring survive, it doesn’t matter whether you suffer through the process. Natural selection is indifferent to your misery.

This sums up my experience of “morning sickness” in the first trimester. Based on depictions on television and film, I expected to promptly throw up each morning after smelling a particularly strong coffee, and then proceed with my day as usual.

I did not expect to feel permanently carsick, chronically exhausted, and always-about-to-vomit from 6am to 6pm, every day, for 8 weeks. This turned out to be fairly debilitating for everyday tasks. Fittingly for stepping into parenthood, I had to start holding my notion of “the kind of person I am” very lightly. Pre-pregnancy-sickness, I had a bunch of moral-high-ground-ideas about the kind of standards I hold myself to on a daily basis.

I thought I was the kind of person who exercised 4+ times a week. And the kind of person who eats large volumes of nutritious vegetables and whole foods. And the kind of person who spends time outside of work creating stuff; writing, drawing, and building things with code.

But I promptly stopped being this kind of person. I exercised 0.3 times a week. The few times I tried to go on runs, it felt like dragging a lead body around. I did not want vegetables in the same room as me. I ate nothing but salt & vinegar crisps, oven chips, marmite toast, and instant noodles. On good days I could do cheese on crackers and meal deal sandwiches . The overriding theme was heavily processed carbs with lots of salt.

In every moment outside of work, I napped, or else I curled myself into a small ball on the sofa and watched hours of TikTok about how to be pregnant and what babies are. I would occasionally take breaks to retch up stomach acid or fetch more crackers to nibble on. I made nothing. I exercised no creativity. I transformed into a very tired, nauseous blob unwilling to do much of anything.

I felt slightly validated when this subjective feeling-like-shit state clearly showed up in my Garmin tracking data. From the moment I found out I was pregnant in mid-July, my resting heart rate began to rise, my stress graph went permanently orange, and my sleep quality dropped.

Even once the first trimester ended and I began to feel more capable, resumed regular exercise, and expanded my diet beyond packaged carbs, my health metrics never recovered. As far as evolution is concerned, this was all fine. I was still alive and healthy and going to reproduce. No biological adjustments needed.

Perhaps in an earlier millenia, this amount of sickness would have been disruptive to gathering enough food or running away from predators. But now that we’ve eliminated those kinds of environmental pressures, we’re not really selecting against people with debilitating morning sickness and slowly reducing it’s presence. Which I’m thankful for! Because I wouldn’t be long for this world. And I should point out than on the scale of severity, mine was pretty middle-of-the-road. Some women get an extreme form of morning sickness called Hyperemesis Gravidarum and end up hospitalised from dehydration and malnutrition.

Rather than being a trait to select against, scientific consensus seems to be that throwing up

everything that isn’t a dry cracker is actually evolutionarily productive and protective. The

theory goes that chronic nausea prevents women consuming toxins

or harmful substances at a time when the fetus is most vulnerable (the first few months). Aversions

to foods like meat, eggs, dairy, and vegetables has some sensible basis since these are more likely

to carry bacteria and parasites than my beloved salt & vinegar crisps

( Flaxman

2000

Arbitrary Fruit Babies

Someone, somewhere once decided the best way to help expecting parents understand the size of their growing child was to compare it to an escalating array of fruits and vegetables. Ever since, this has become the global standard in every last pregnancy guide and app.

Each week you get a produce update. Last week, an avocado, this week, an artichoke, next week, a mango, the week after, a sweet potato. Despite the widespread prevalence of this adorable set of comparisons, there is, shockingly, no standardised fruit schedule for everyone to align to. Each app picks a completely different arbitrary plant each week.

I just need to point out there’s an enourmous opportunity here to someone to propose a standardised fruit comparison schedule for everyone to align to and end the chaos. It’s probably not a lucrative economic opportunity but I’m sure you’ll get lots of scientific street cred for it.

Produce relativism also becomes a problem. Being told your baby is the size of a cucumber begs the question, “what kind of cucumber?” A cucumber can be anywhere from 10-40cm depending on the cucumber. Are we talking Persian cucumbers? Hothouses? Marketmores?

Suffice to say I haven’t found the fruit comparisons particularly helpful for visualising how the baby is coming along, but appreciate there aren’t many other categories of objects in the world we could swap it out for. Comparisons to animals would be too taboo. No one wants to be told their baby is a grouse this week. And household objects are too inert and objectifying; “your baby is a whisk” doesn’t have the same adorable, natural-goodness factor.

Unconscious Expertise and Existential Vibes

A few months ago I grew a pair of kidneys. I haven’t a clue how. If you asked the conscious, problem-solving, goal-directed, “intelligent” pre-frontal cortex part of me how to grow a kidney, she wouldn’t have a good answer.

This unconscious intelligence felt most visceral at the 20 week “anomoly scan” where they check your baby for any physical abnormalities or issues. When the ultrasound technician swiped her cold wand across my stomach and the large-screen monitor across the room lit up to reveal an entire spine, complete with 33 tiny vertebrae each with it’s own intricate and delicate set of spikes poking out of it, gently wiggling back and forth, I got my first real wave of disbelief about the situation.

If you hadn’t guessed already, I’m not a woman of faith. At least not in the sense of temples or Allah or throwing blessed-by-Christ-holy-water on people. I don’t have a weekly standing appointment to reflect on my place in the universe and bow down before higher-order beings. But I do carry around a strong sense of reverence and awe for higher-order forces; the unreasonable effectiveness of evolution, the tectonic plates floating about on molten mantle sculpting our earth, the symbiotic relationship between clownfish and sea anemones, the fact trees warn each other of dangers via chemical signals and send reinforcements, the mystery of consciousness, and whatever the fuck is going on with black holes. These things all give me Carl Sagan’s energy marvelling at the pale blue dot .

Growing a small human has turned up the dial on that existential awe and become an unexpectedly profound experience for me. More so than any of my other earthly pursuits. Every time the little creature kicks me or flops over in my stomach, I’m flooded with a sense of marvel in the most unjaded way possible. Which is saying a lot for someone raised in a world of staunch atheism, skepticism, and a low tolerance for anything vibey or woo.

After decades of existing in a culture that worships rational, modern, scientific knowledge, preferably “discovered” within the last 500 years, it’s been humbling to realise how much the pre-modern, animalistic parts of me know and are capable of. And how much of me feels innately, sub-consciously designed to want this and be perfectly equipped to do it.

Perhaps I shouldn’t say “I” am growing this baby, because “I” – as a conscious being with a sense of self, skills, and goals – have little to do with the process unfolding in my midsection. The instructions for how each cell should divide up into kidneys and vertebrae and adorable toes are not coming from me. They’re baked into the precise combination of DNA this little one ended up with. It’s evolution following a set of protocols and best practices. It is not “me” growing the baby, any more than it’s “me” filtering out toxins in my kidneys right now. Which is a relief! And feels a lot like the trust and surrender religious people talk about when they say things like “it’s in God’s hands.” For me, it’s in millions of years of evolution’s hands.

All Natural, Organic, Granola, Earth Mothering

Naturalness is a major concern in Motherland. I acknowledge not all primary parents are women/mothers and I shouldn’t be unjustly gendering this, but if you go look for parenting content online you will have to acknowledge this is an overwhelmingly female space. It’s silly to pretend 99% of the people making and engaging with pregnancy content are not women. Every kind of pregnancy content I’ve consumed – advice books, Tiktok and YouTube videos, Instagram influencer stories, podcasts, unhinged Mumsnet posts – all share a consistent theme: the mandate to maximise Nature in your pregnancy.

Potential new mothers are urged to eat only natural foods, take natural supplements, prepare to naturally breastfeed, buy natural organic baby clothing, stock up on natural, wooden toys and chemical-free lotions and eco-friendly cloth diapers, consider names inspired by nature, learn natural parenting methods like babywearing and co-sleeping, and tap into their natural mothering instincts.

This vibe seems especially potent in the current zeitgeist of trad wives living on Utah farms , collecting morning eggs, making yogurt and sourdough from scratch, and dressing their eleven children in home-spun organic cotton frocks. These women are apt to describe themselves as “a bit granola” or “crunchy.”

As evidenced in the previous section, I am entirely on board with trusting our pre-industrial bodies and acknowledging the limits of modern knowledge. New parents of vulnerable babies are justified in their skepticism of novel, untested, and potentially harmful things. But the tidal wave of “naturalness” in motherland lacks much critical thinking or nuance.

There is a blind labelling of anything natural as inherently better. Natural food is healthier for you. Natural substances are safer. Natural lighting is more pleasant and tuned to your circadian cycles. Natural ways of living are more in line with our biology. Natural parenting techniques have stood the test of time. Natural colours like beiges and browns have become an all-purpose signifier of purity and goodness, leading to a proliferation of “ sad beige mums ” exclusively purchasing neutral-coloured baby clothing, toys, and nursery items. Even though making a onesie or a pacifier brown doesn’t make it any safer or closer to the earth than a red, purple, or blue one.

Unnatural, man-made things like plastics, chemicals, pesticides, pollution, additives, genetic modifications, high-fructose corn syrup, cheetos, polyester, screens, and fluorescent lights are always framed as bad, harmful, and to be avoided at all costs. To be clear, most of these things are indeed harmful and should be avoided, but not because they’re unnatural and humans made them. It’s because they have harmful properties which we’ve discovered through scientific research and reasoning. Plenty of “natural” things like asbestos, mercury, and arsenic are equally dangerous.

The attempted simplification of the world into these two clear categories – natural and unnatural – is both false, and a source of endless confusion, conflict, and poorly made decisions.

That’s because “nature” and “culture” are not two fixed, distinct, and absolute types we can sort everything into; there’s no clear-cut set of safe, pure things unmarked by human influence, and another of dangerous, artificial things tainted by us. Human and non-human things are always entangled and shaped by one another.

Anthropologist Donna Haraway was one the first to

argue this in her 1991 book

Simians, Cyborgs, and Women . This

was an expansion on her earlier essay

A Cyborg Manifesto

(1985), and she later wrote

The Companion Species Manifesto

(2003) followed this same line of thinking. I should also mention

Bruno Latour ’s

We Have Never Been Modern (1991) –

another foundational text for this theory. Sadly, both Haraway and Latour are horrendous writers and

trying to understand their original texts is a laborious and baffling process, which is probably why

they’re not more widely known. In it, she critiques our moden approach to seeing the

world in clear dualities: human/animal, machine/organic, male/female, and natural/cultural. She

instead advocates for a more holistic, hybridised, and interconnected view of the world – one she

calls “ natureculture Natureculture, Moral Purity, and Cultural Boundaries

Why there is nothing natural about the idea of 'nature' ” – that recognizes that nothing is ever purely one or the other. People,

creatures, objects, and ideas are always hybrids of these categories. Cultural, social, and

technological forces transform what we might otherwise label as “natural,” while natural systems

shape and influence our cultural, social, and technological realms. These false divisions have been

socially and historically constructed, and do not exist a priori in the world. “Nature” is a concept

we invented to draw a line between ourselves and the earth – a tool for asserting human uniqueness

and separation that became an obsession during the scientific revolution of the 17th and 18th

centuries ( Latour 1991 ).

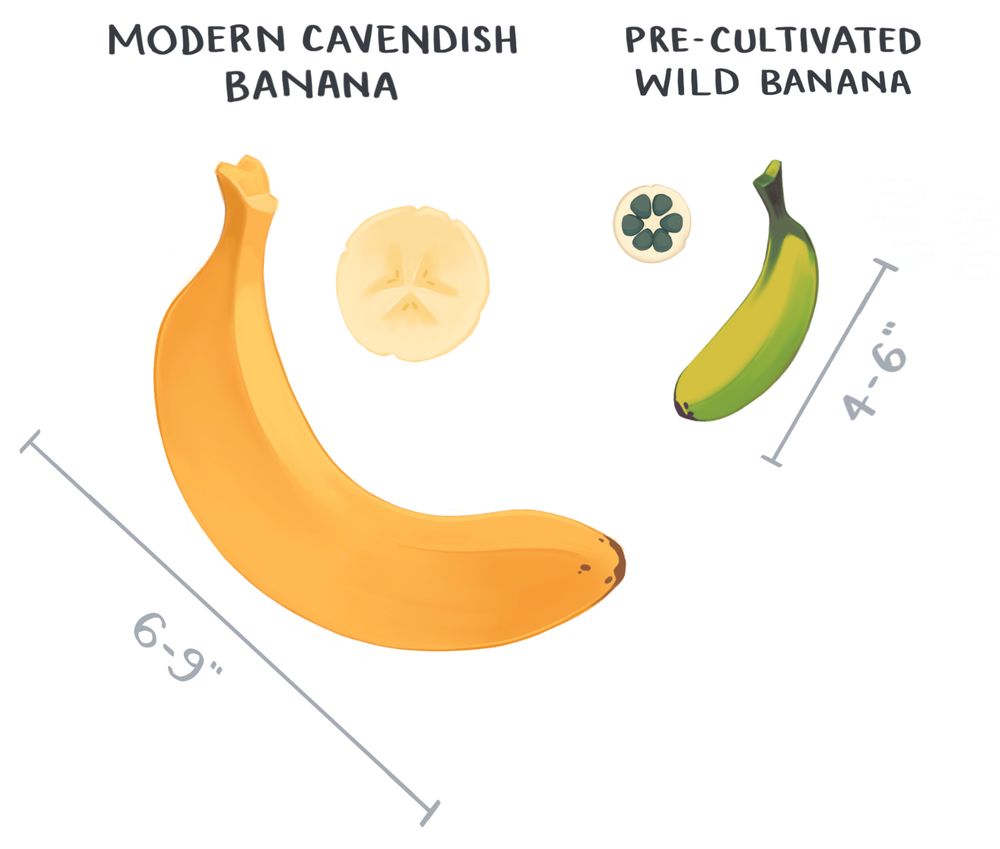

Bananas are a prime example of a natureculture hybrid. 10,000 years ago, wild bananas were small, fibrous, bitter fruits filled with large, hard seeds and not much flesh. We know this because we’ve found phytoliths of these unappealing bananas in sediment layers of swamps in Papua New Guinea and Southeast Asia dating to at least 7,000 y.a. and up to 10,000 y.a. These ancient bananas match some species of wild bananas that still exist today. These swamps are our earliest evidence of banana cultivation. They offered little sustenance and look nothing like the bananas we buy today.

But they had enough potential for humans to start cultivating them. Once we began selecting the

larger, sweeter, less seedy ones and planting more of them, bananas began their slow transformation

into what we’re used to today; the huge Cavendish variety with teeny tiny seeds, lots of sweet

flesh, and thick skins to survive their journey through the grocery supply chain

( Perrier

2011

If you went down to the grocery store and bought an organic banana, is that banana natural or unnatural? Do you think this cultivated banana is somehow worse than its pre-historic wild counterpart? Is feeding it to your child going to harm them in some way?

There are countless such cases where humans and other creatures, environments, and substances have not just influenced each other but adapted and co-evolved together as hybrids; corn and wheat shaped by cultivation just like bananas, dogs becoming more docile and cooperative , Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus bacteria feeding on Cheerios and Chobani in our gut microbiomes, coral reefs adapting to survive in warming oceans , the 12 million children born by IVF, foxes and pigeons flourishing in cities on trash diets, seasonal flu viruses mutating into aggressive new strains, babies with larger head sizes caused by an increase in cesarean births, and plastic-eating bacteria cleaning up our pollution are all cases of deep, complex entanglements. Where nature ends and culture begins is a murky tangle.

Understanding that “nature” is an imagined category, and not one that necessarily correlates to safer, purer, and better, makes achieving the ideal of natural parenting a touch harder. Instead of being able to assess the safety and goodness of food, toys, and parenting practices based on how untouched by human modernity they seem, we have to rely on other kinds of decision-making. Like considering what makes sense within our particular cultural contexts, using our critical thinking skills, and trusting the most unnatural of things: published, peer-reviewed scientific studies containing hard evidence.

This kind of research and analysis takes a lot of effort though, so it’s understandable people resort to easier heuristic shortcuts like “all brown things are safe.” We should at least acknowledge we’re engaging in a convenient delusion while we do it.

Traditional and Tribal Parenting

The recent idealisation of “traditional” parenting cultures is a prime example of this inconvenient confusion. There’s been a growing interest in how people from non-WEIRD Western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic. Loosely, the cultures of North America and Europe. More on this demographic categorisation here . nations and cultures approach pregnancy and child rearing. Popular books like Hunt, Gather, Parent : What Ancient Cultures Can Teach Us About the Lost Art of Raising Happy, Helpful Little Humans (2021) popularised a semi-anthropological approach of looking to cultures like the Mayans of Mexico, Inuits of the Arctic, and Hadzabe of Tanzania for advice on how to raise children. Practices like babywearing, co-sleeping, baby-led weaning, elimination communication, gentle parenting, extended breastfeeding, and communal childcare have all become more popular as “traditional” ways of parenting. Social media mumfluencers will often invoke imagery of hunter-gatherer societies and pre-historic ancestors running about in tribes to promote these practices, using them as evidence for their inherent goodness.

The unspoken assumption here is that non-WEIRD and subsistence cultures like the Mayans, Inuits, and Hadzabe have lifestyles closer to pre-historic humans than ours, and therefore their parenting approaches are more natural and preferable. And they might be! Lots of these practices have been passed down through many generations, are sensible, and backed up by good evidence.

But I think it’s helpful to remember:

- People from non-WEIRD cultures are not living in a static society that hasn’t been changed or transformed by modern practices. They are not ancestral people frozen in time, untouched by cultural evolution. Their practices are not necessarily the One True Natural Ideal of pre-historic life.

- Our pre-modern ancestors (and the cultures we try to use as stand-ins for them) might not be the

best model for ideal parenting in the 21st century. They not only led drastically different lives

to us, with different restrictions and needs, but also had much higher rates of child mortality,

disease, and suffering, and both procreated and died much younger than we

do. Our estimates are that hunter-gatherer women had their first

child at 18

and 49% of those children died before reaching puberty

( Our World in Data ) Idealising their

lives as superior and preferable to our own is classic Paleolithic Nostalgia

Paleolithic Nostalgia

Longing for the paleolithic past in the Anthropocene .

This blanket idealisation also overlooks the fact that some non-WEIRD societies tolerate seemingly brutal parenting practices. Infanticide is not uncommon. The Ache hunter-gathers of Paraguay buried babies born in the breech position, without hair, or with visible disabilities. When an adult member of the community died, at least one child was thrown into the grave with them ( Small 1998 ). Similarly, several cultures in sub-Saharan Africa historically killed twins at birth, believing them to bring bad luck ( Fenske and Wang 2023 ).

Killing aside, subsistence communities constantly on the move — spending their days doing physical labour and living in environments filled with harsh weather, wild animals, and poisonous plants — simply have very different needs from a yummy mummy living in Greenwich or Guildford. Constant babywearing, breastfeeding, and co-sleeping are less critical for survival when you’re in a heated flat equipped with a Snoo , a baby barista , and a rotating selection of ergonomic bouncers from John Lewis.

“Achieving” Natural Birth

I found the blind reverence for nature most complex when it comes to birth itself. Specifically, advice on how to “achieve” many women’s assumed goal of an all-natural, unmedicated birth. Most of the birthing advice content on YouTube and Instagram focuses on eschewing unnatural, modern interventions like hospital wards and pain-relieving drugs like epidurals. An epidural is an injection into the spine that numbs the lower half of the body, providing effective pain relief for women in labour. The top-rated birthing books on everyone’s lists, like Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth and Hypnobirthing , convincingly argue birth is the most natural thing in the world, and should not require medical assistance.

They instead promise that if you set up a birthing pool at home, surround yourself with candles, and learn a few deep breathing techniques, birth can be a relatively painless, peaceful, and empowering experience. They say we shouldn’t talk about “pain” during birth, but instead use words like “intensity” and “power.” These books are filled with accounts of women ecstatically giving birth leaning against a tree and channelling their inner animal under the moonlight. I will concede these stories are primary in the Ina May book but read as even more hippie and unhinged than I’ve described here.

Now, I have absolutely no expertise or experience yet of birth. But I’ve surveyed every woman I know with children, and watched one too many online videos of live birth vlogs, and the consistent theme across the board is that women both report, or clearly appear to be experiencing, previously unfathomable levels agony throughout the process. Common descriptions include “feeling like I was being torn in half” or “having my guts shoved out of me” or “like shitting out a watermelon” or “I’m too traumatised to talk about it”. And if we’ve learned anything in recent years, it’s that we should Believe Women.

So there appears to be some disconnect going on between the ideal, natural birth experience women are being told they should try to achieve, and the reported reality of most people’s birth experiences. The people who dole out birth advice are quick to say there are no wrong choices and everyone’s personal preferences should be respected. But I’m personally confused by the idealisation of subjecting yourself to tremendous levels of pain in the service of doing things “the natural way”. As established previously, nature doesn’t care much about your comfort or enjoyment, only that your offspring survive.

Syphilis is also “natural”. And I’m personally planning on getting an epidural.

Pregnancy Before Pixels

Once I started talking to the seasoned women of my family about their pregnancy experiences – my mother, mother-in-law, and still-kicking-94-year-old grandmother – terrifying stories quickly emerged. Not of birth pain or devastating losses. But simply of the standard of maternity care, available medical knowledge, legal rights, and technical capabilities available to pregnant women only 30-60 years ago.

Some of these generational differences of opinion are endearing; both my mother and grandmother are concerned I’m continuing to work out throughout pregnancy. They suggested running might make the baby too used to bouncing movements. It might demand constant bobbing upon arrival. Or become one of those intolerable hyperactive children. Weight lifting might stress the baby out or accidently pop it out too early.

These worries sort of make logical sense. In their day, pregnancy was a time for quiet rest, not

sprinting around. But the point of science is we sometimes discover our intuitions are wrong.

Studies overwhelmingly show doing cardiovascular exercise and strength training throughout pregnancy

both have huge positive outcomes for both mother and child. Improved bone density. Improved stress

levels. Improved newborn growth and neurodevelopment. Fewer cesaraian sections. Shorter recovery

times after birth. Lower risk of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, postnatal depression, and

pelvic floor disorders.( Perales 2016

Access to scientific research and medical insight was sparse across the board. My parents, born in the late 1950s and early 60s, never had ultrasounds done of them in the womb. Because ultrasounds, the primary way we check that babies are alive and have all ten fingers and toes, a beating heart, intact spinal cords, the right number of kidneys, and limbs where they should be, weren’t widely available until the 1970s .

My grandmothers had no way of knowing if the child inside of them had a serious disability or medical issue. They had no way to check for chromosomal abnormalities like Down’s Syndrome. Let alone the baby’s sex ahead of time – something we can find out today at only 6 weeks in with a £90 blood test . Both told stories of pregnancy being a time of terrible worry and concern. Of being beside themselves thinking they might give birth to a stillborn, or a severely disabled child to care for on top of their existing children, and no choice in the matter.

The differences in outcomes between their generation and mine is staggering. If we compare today to

1960, stillbirth rates have dropped by 80%

Statistics are nice but what strikes me is the emotional difference in how I’m able to experience pregnancy versus the uncertainty and anxiety they had to endure.

Unlike my grandmothers, I’ve been given a flood of reassuring information to help me adjust my expectations to the reality of my pregnancy. I have seen my baby kick and flail its arms on a small video screen. I’ve had blood tests to check for concerning chromosomal issues. An experienced sonographer has measured the length of every major bone in my baby’s body, it’s heart chambers, and lung capacity. A kindly midwife checks my vitals and mental health every 5 weeks to ensure I’m doing as well as the baby is.

Even so, my experience is still brimming with the possibility of loss. From the beginning that has been clear. The minute you realise you’ve been cosmically promised a tiny, perfect, unbearably lovely child to care for, you suddenly realise all the ways that can be taken away from you. Rare diseases. Unforeseen complications. Foreseen complications. Traumatic births. Random chance.

While modern medicine can’t prevent every last prenatal tragedy, it can see far more of them coming down the pike, and prepare parents for difficult realities. And more importantly, medically intervene or give them choices ahead of time. Choices that are astonishingly being taken away from parents in increasingly medieval and oppressive countries like the United States. Weird to say, but god bless the United Kingdom 🇬🇧

My pregnancy isn’t marked by fear and worry about the health of my child, or my own survival through this process, in the way my grandmothers were. My doctors and midwives not only care for me, but grant me the right to make choices about my own body and child. In ways my grandmothers weren’t given choices or cared for at all. Before we realised pregnant women might need some information, rights, and emotional support.

And all I can feel is shocking, overwhelming gratitude to be pregnant at this point in history.

Some Helpful Recommendations, So Far

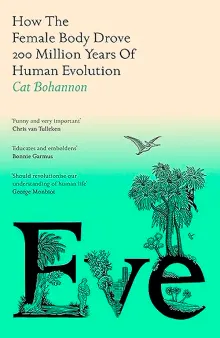

A major upside of being pregnant is you get to launch an extensive research project complete with literature reviews, spreadsheets, and buy dozens of new books, and your partner can’t protest. It’s all for the good of the baby!

Most of the books in this space are a bit meh both in terms of information quality and comprehensiveness. There’s a lot of very large text, decorative call-out boxes, and almost no references to sources or scientific studies. But I’ve found a couple of good exceptions:

Aside from books, I’ve found the thousands of mumfluencers on Tiktok, Instagram, and YouTube surprisingly useful sources of insight. Despite having spent the majority of this essay critiquing them… some clearly need to be taken with a large grain of salt. But never before in history have expecting parents had access to so many opinions and perspectives on everything from sleep training to newborn essentials to postpartum exercise. Our parents had a small handful of books that told them the essentials and blissful ignorance about the rest of it.

Vinted is a popular second-hand marketplace here in the UK where I’ve bought almost everything we need for baby at a tiny fraction of the retail price.

Expecting and Empowered is a strength training app designed for pregnant women that guides you through safe exercises for every trimester. I do in-person classes in addition to this at a local gym, but E&E helps me understand how to safely lift and adapt movements as my bump gets bigger, and gives me ideas for alternative exercises. I’ve also heard good things about Hatch Athletic .