Art by the most famous artists in the world has never been more aesthetic than it is now. Between its creation a few centuries ago and today, everyone’s art has gotten brighter, more colourful, more dramatic, more aesthetically pleasing, better composed, and more desireable.

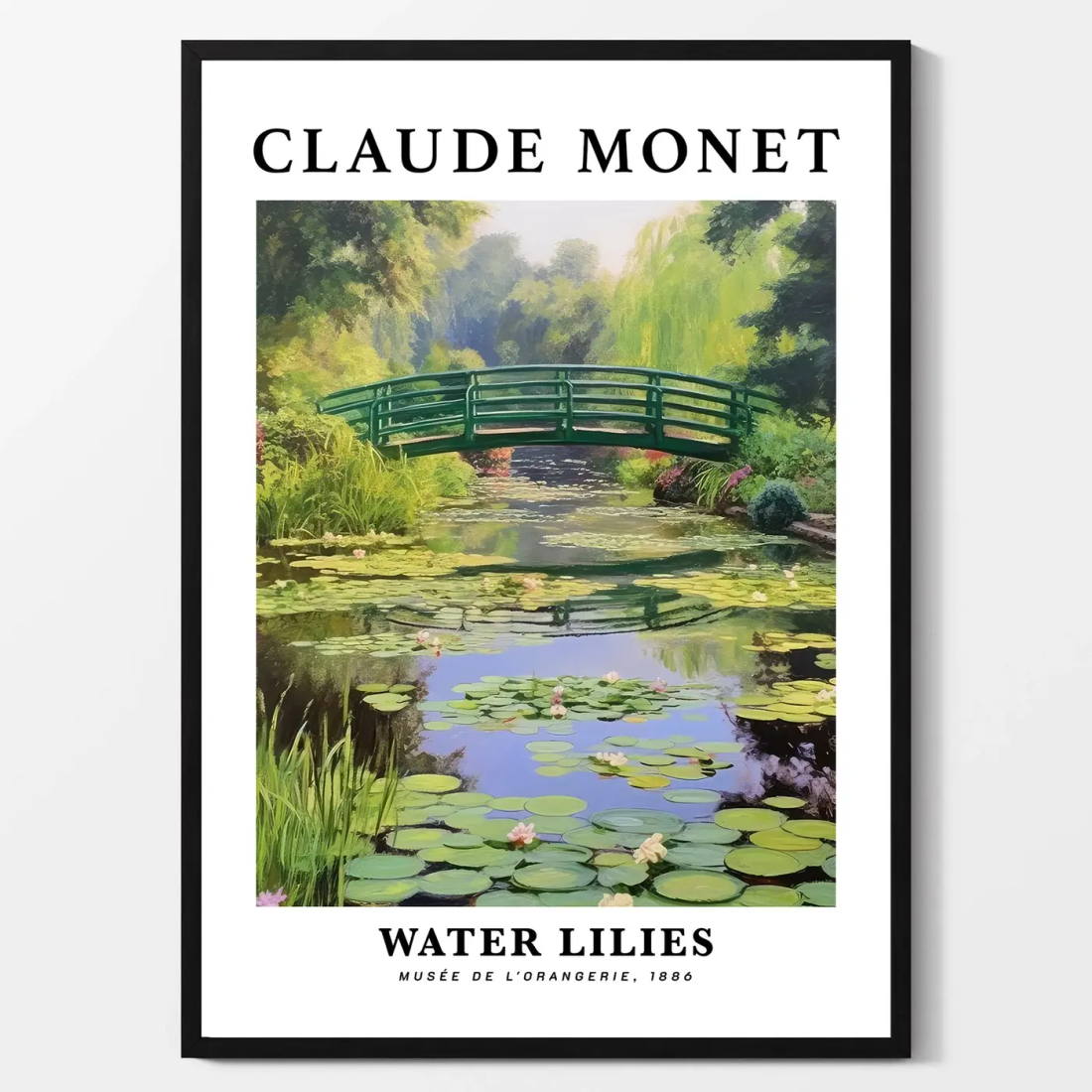

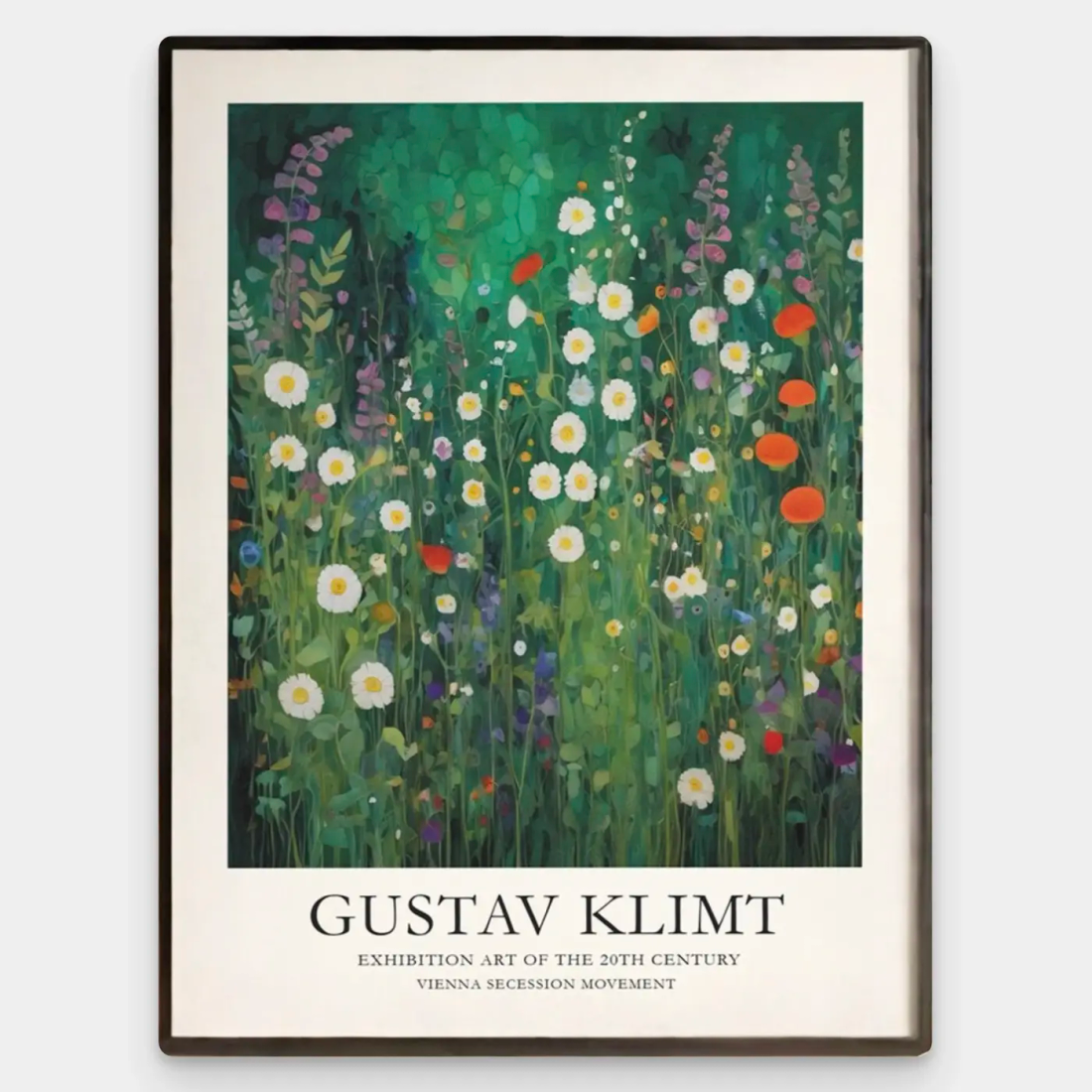

While Monet, Van Gogh, Klimt, and Matisse are sleeping in their graves, we’ve been busy improving their life’s work. The Water Lily Pond might have wowed people in 1904, but it’s looking a little pale and boring in 2024, and it could do with an upgrade.

Fear not; sellers on Etsy are all over this problem. When you go looking for prints by infamous artists on there, you’ll be pleasantly surprised by the huge range of options. There are way more pieces of artwork than you remember any of these artists creating. How were they so prolific??

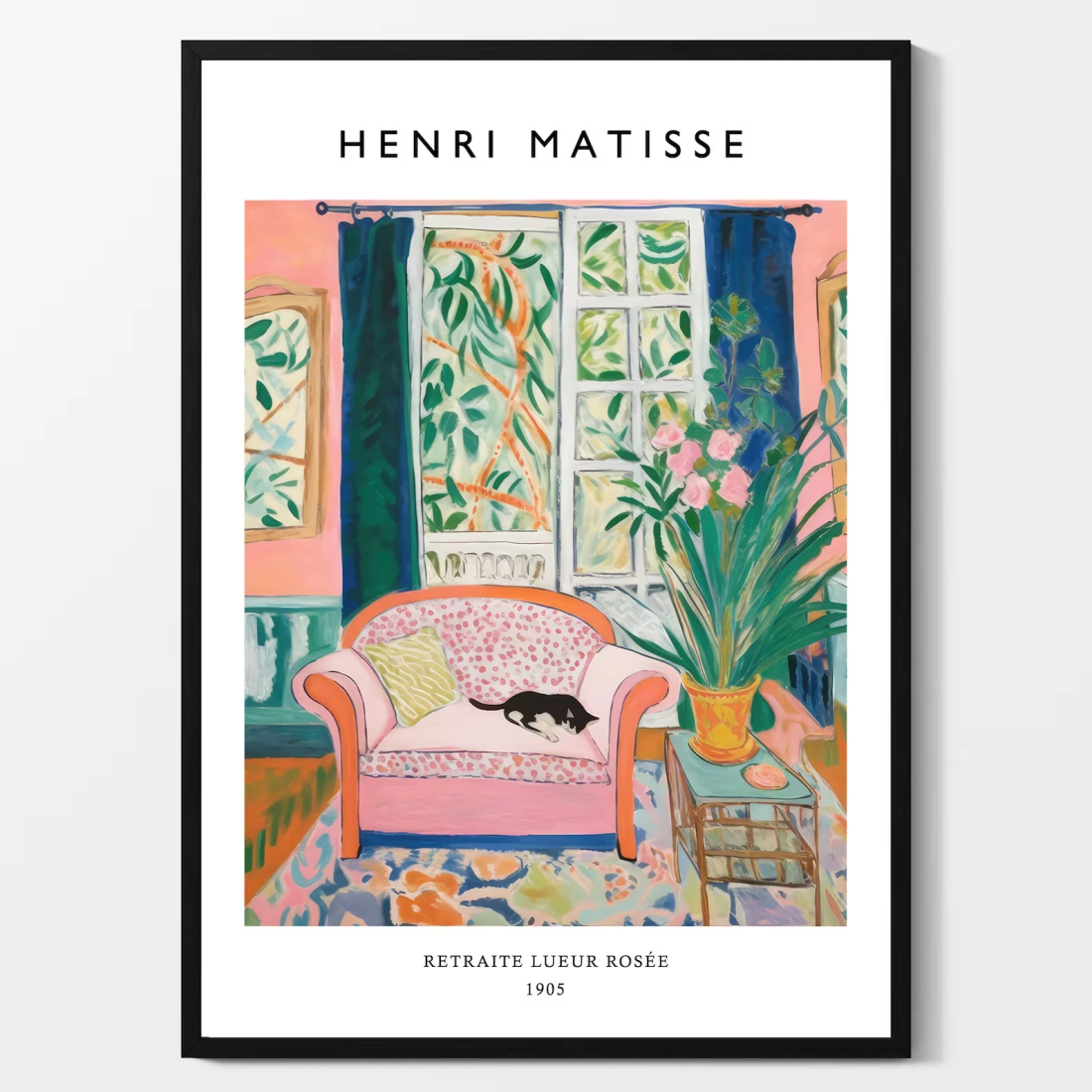

And the artwork itself will hit you differently. Monet’s landscapes didn’t seem this vivid on a screen projector in art class. Matisse’s use of shapes and colours seems more experimental and bold than you remembered. Van Gogh’s work is more detailed than it looked in textbooks.

How did you fail to appreciate this craftsmanship when you first saw it? Why hadn’t you explored their full bodies of work beyond the classics? And why does it all seem so much more impressive now?

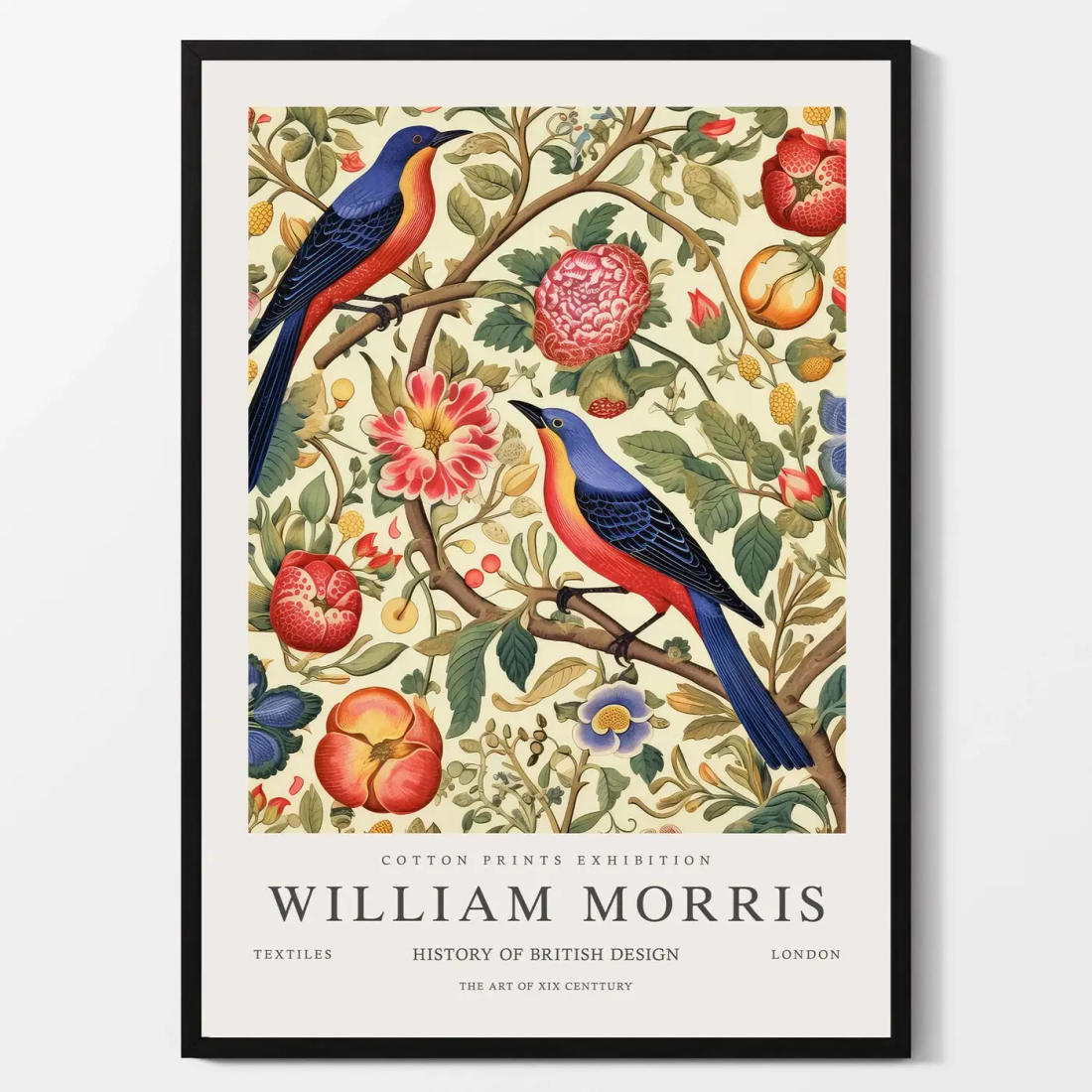

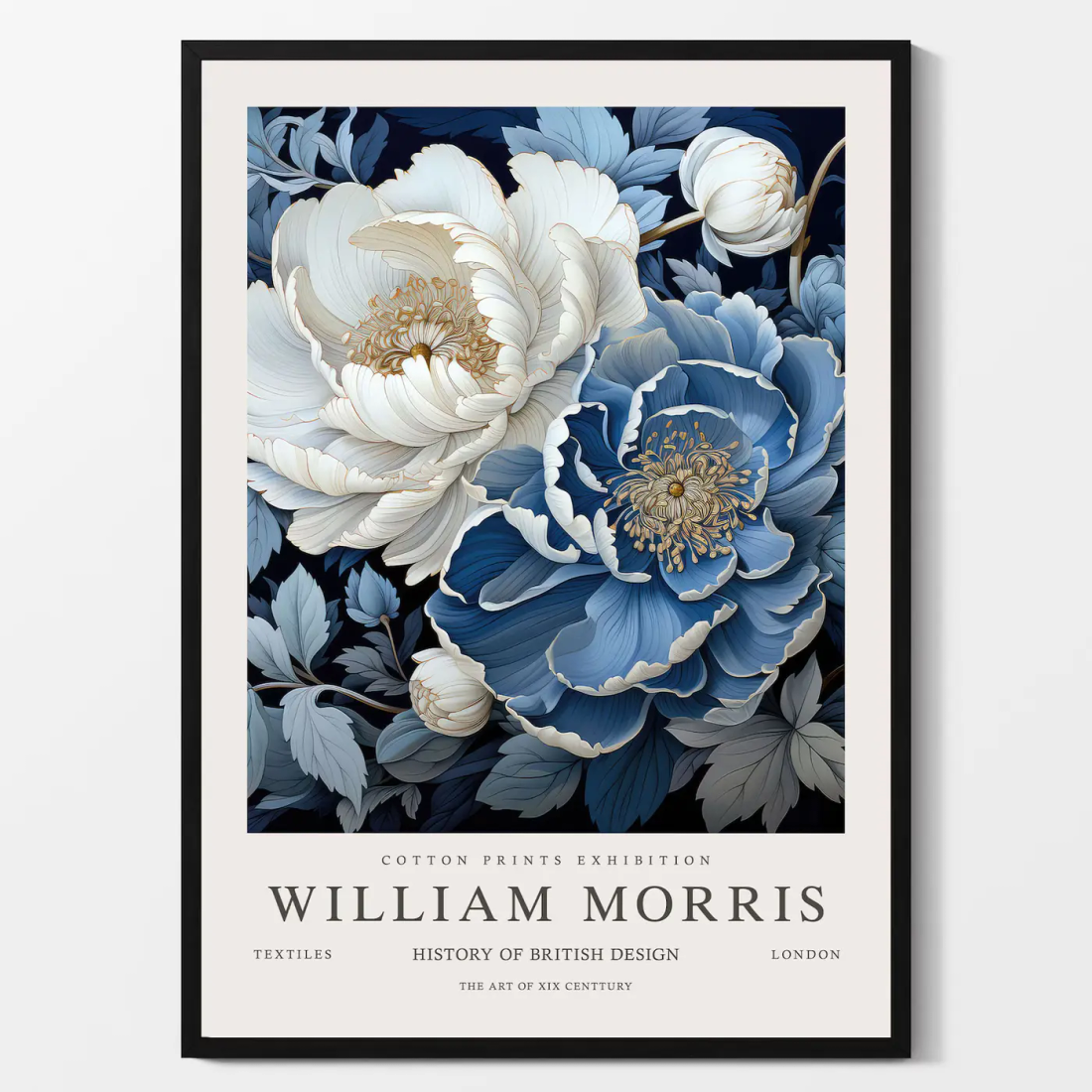

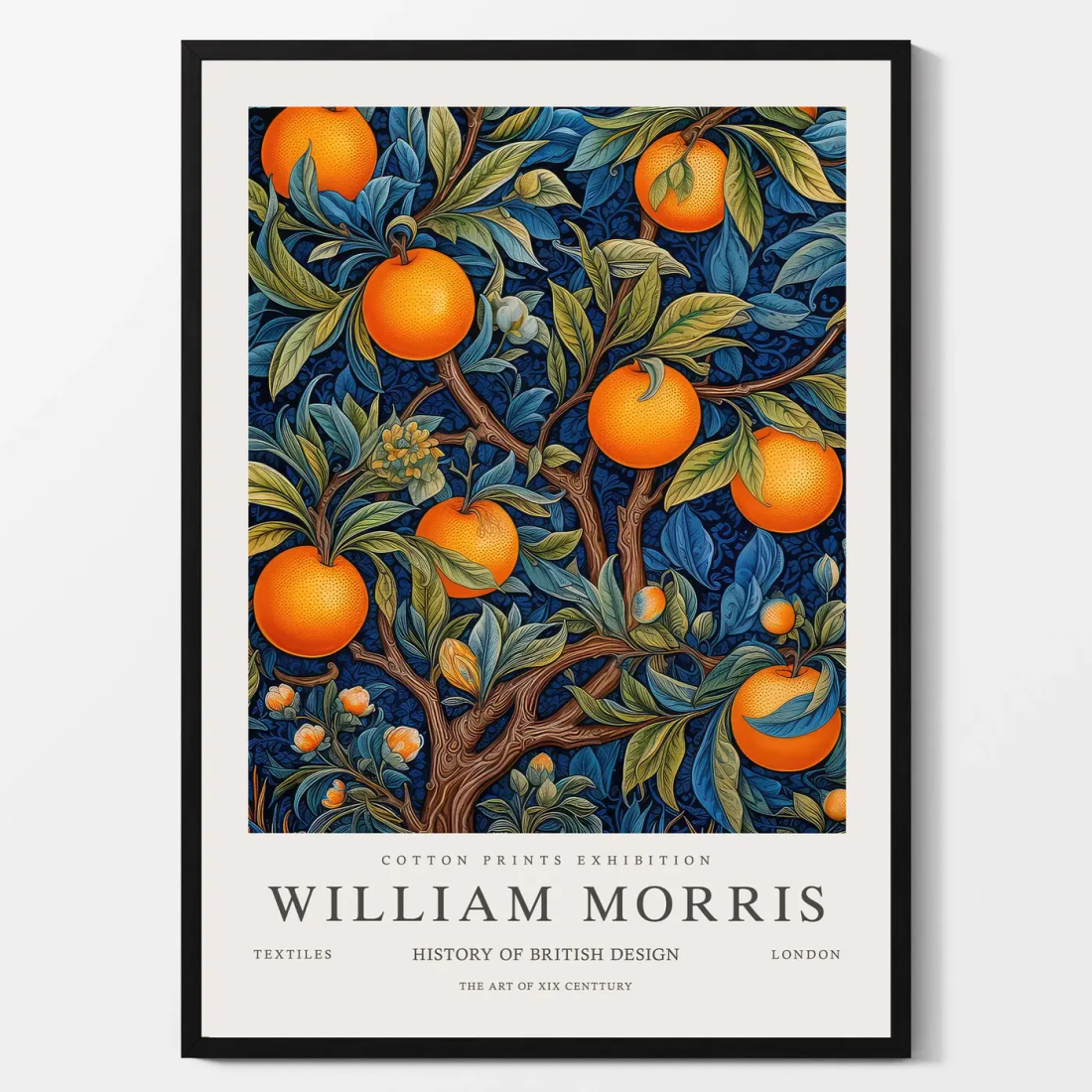

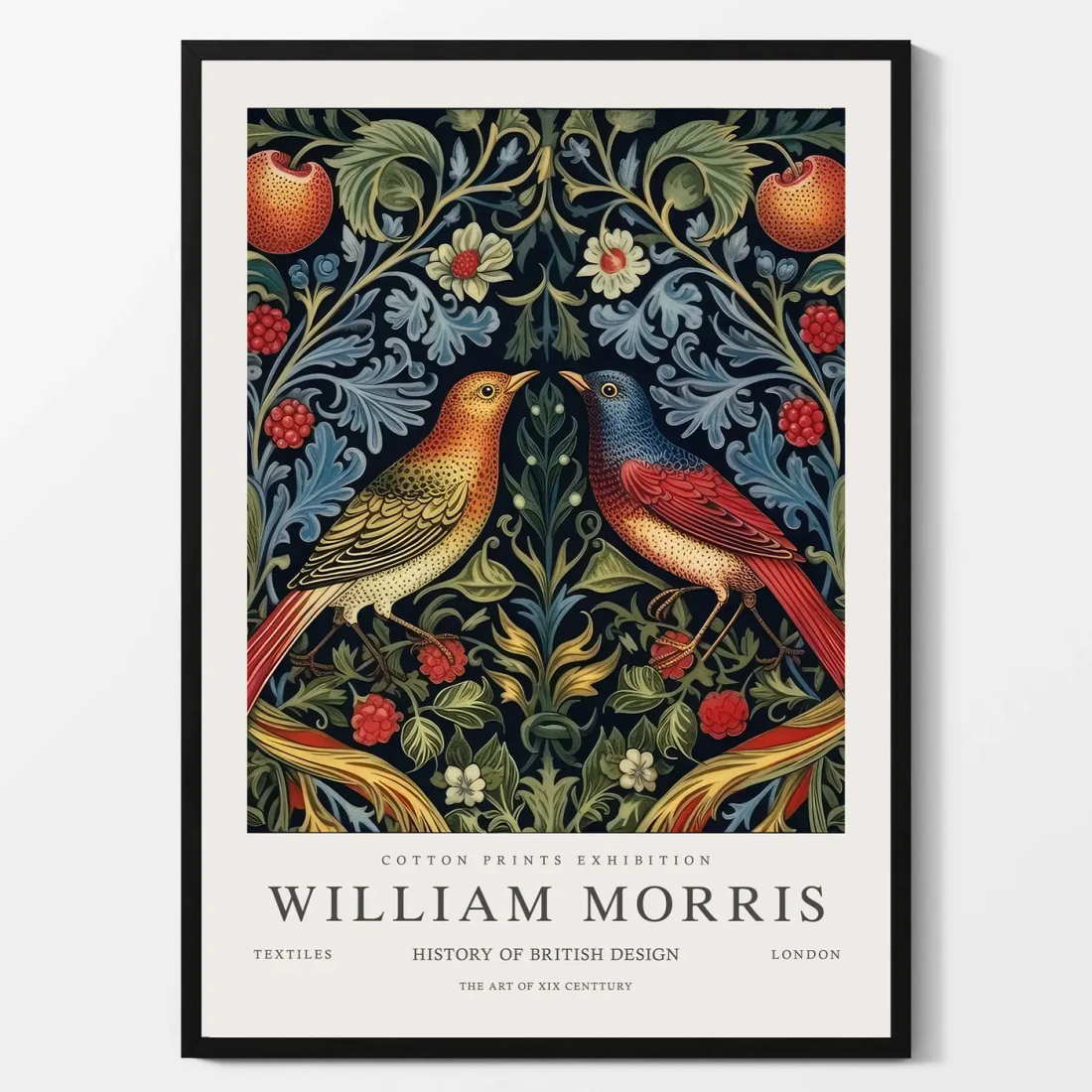

I asked myself all these questions as I scrolled through rows and rows of beautifully aesthetic William Morris prints, liberally adding them to my shopping cart.

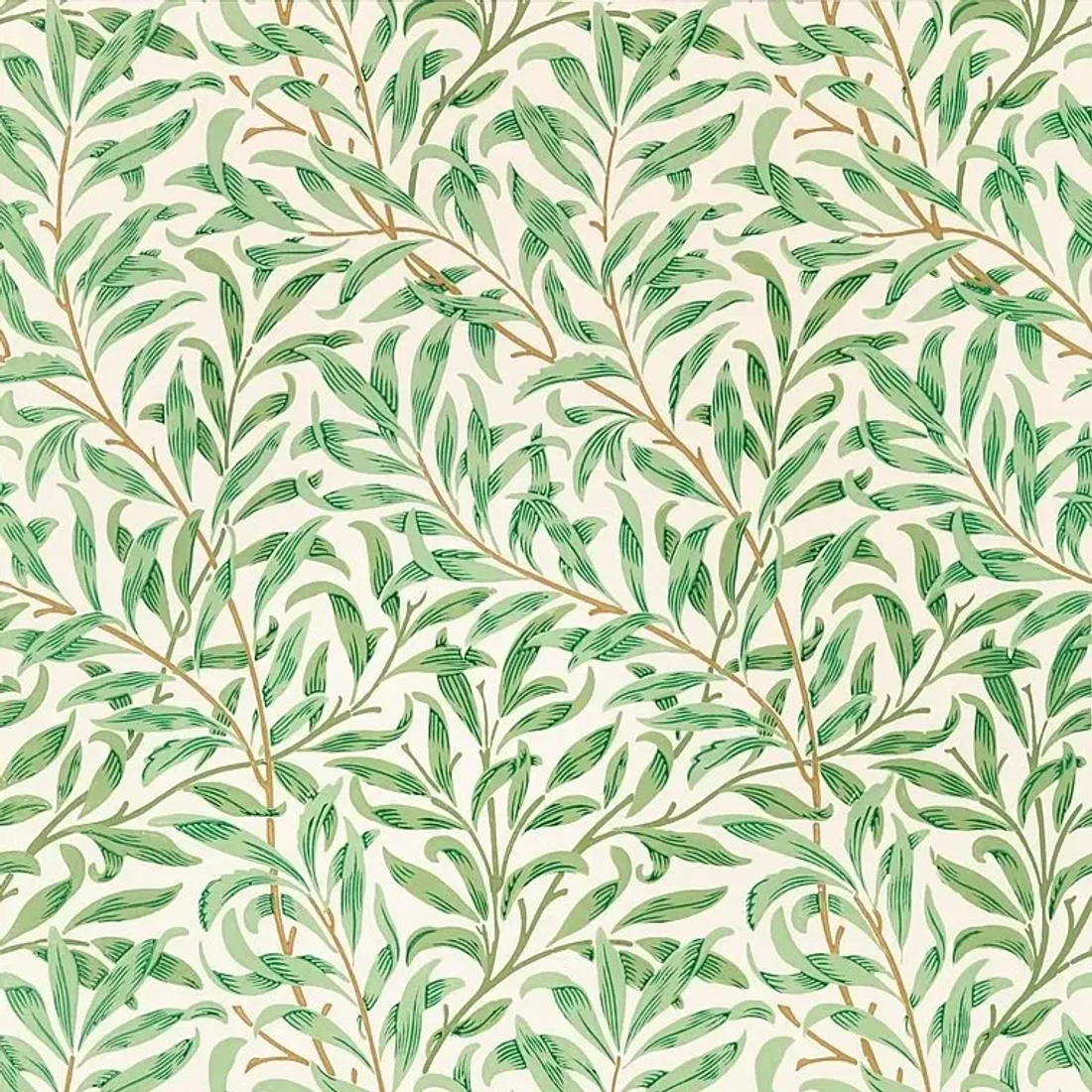

I knew Morris was a British print-maker from the mid-1800’s, famous for designing wallpaper and textile patterns, while still finding time for community organising and promoting socialist ideals. I’d heard of his famous Strawberry Thief pattern and seen his intricate floral designs on everything from teatowels to tote bags here in London.

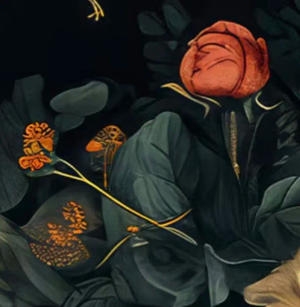

But I’d never seen this collection of his work. I was shocked and delighted to discover Morris was somehow also a fine-art illustrator?? No one had ever told me. And a way better illustrator than I would have imagined. These prints echoed his other work, but with far more detail, rich colours, and compositional beauty. Perhaps he did these later in life? Perhaps the other work I’d seen was by a younger, less skilled Morris?

I was confused, but distracted by a set of important decisions; should I get the bee or the bird print? Should I get the matching pair of blue flower prints or was one enough? Would an A2 print be large enough to see all the lovely details?

Wrapped up in the thrill of discovering this new, delightful art and securing versions of it to gaze at while stirring tea in the morning, my dark, skeptical, spidey-senses failed to engage. High on consumer dopamine and browsing picture frames, I forgot, for an important moment, that we recently crossed over into a different sort of world.

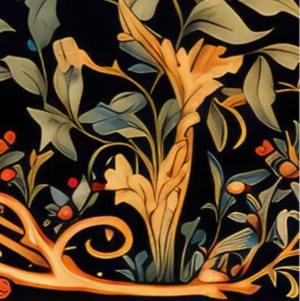

The sort of world where it is trivial to prompt a neural network to create an image that pulls on the traditional patterns, subject matter, and motifs of William Morris, but layered with the hyper-realistic, high-definition, pixel-perfect asethetics of the modern web; dramatic lighting and sweeping landscapes ripped from ArtStation, meticulously art-directed details from Wes Anderson film stills, the two-tone color overlays and soft glow effects popularised on Instagram and Pinterest. A system trained on everything we’ve clicked like on, priming us to like what it makes.

I finally thought to ask the now-blindingly-obvious-question; what if William Morris didn’t make these?

I tried reverse image searching a few of the prints, only to find they were one-of-a-kind. I started googling “morris artwork” and found images that, while beautiful, seemed to lack the finesse and colour range of my new prints.

It was well past time to withdraw the benefit of my doubt.

I zoomed in on some of the prints to find tell-tale artefacts of generated images. Most had inconsistent patterns and incomplete objects in the backgrounds and corners. Elements blurred into one another, with tenative edges and unusual shapes – quirks I’ve learned to recognise from plenty of late nights playing with MidJourney .

I rechecked the Etsy print listings for disclaimers or details I must have missed the first time around, but none appeared. Nothing said these prints were “inspired by” or “influnced by” or “made to mimic” or any other derivatives of Morris, rather than originals.

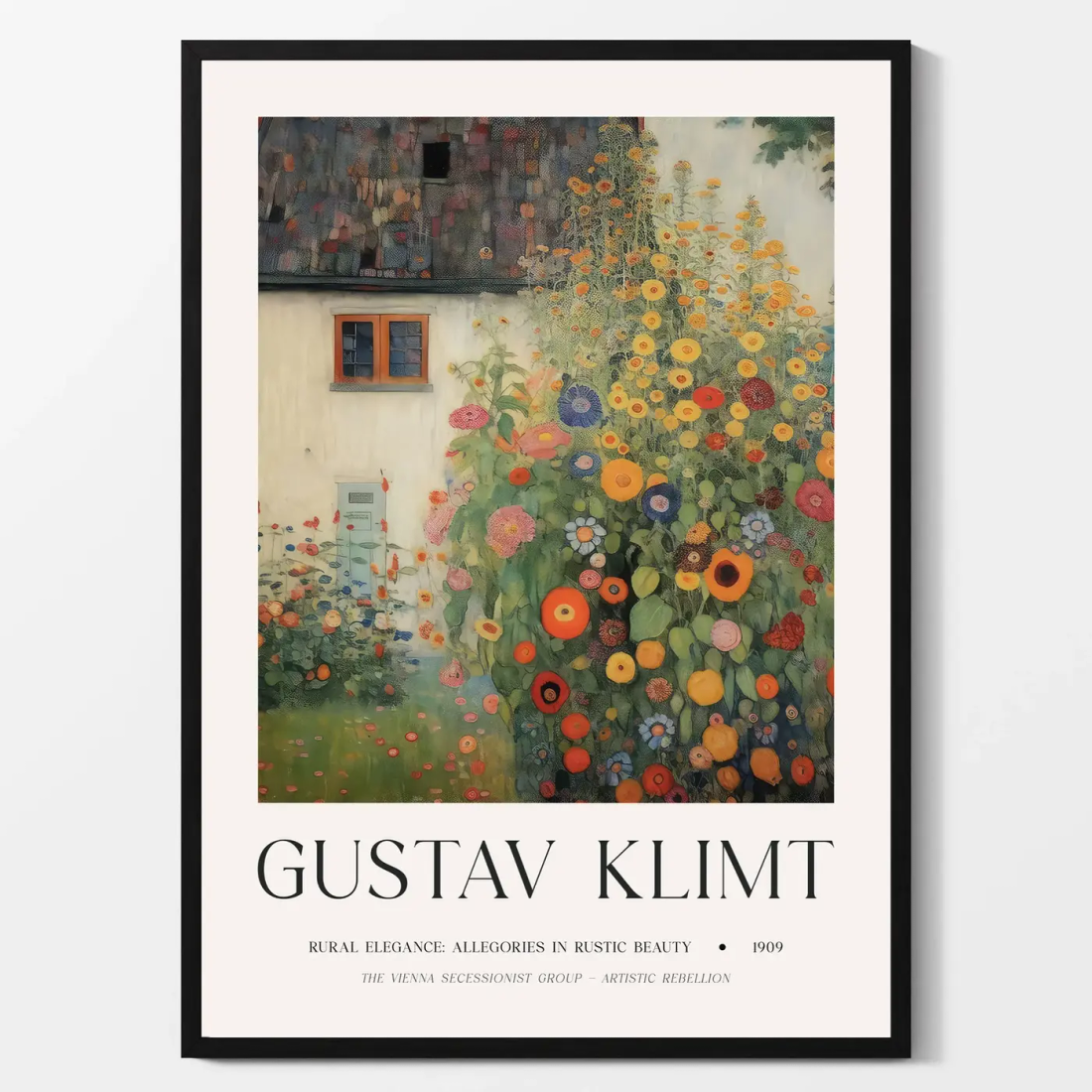

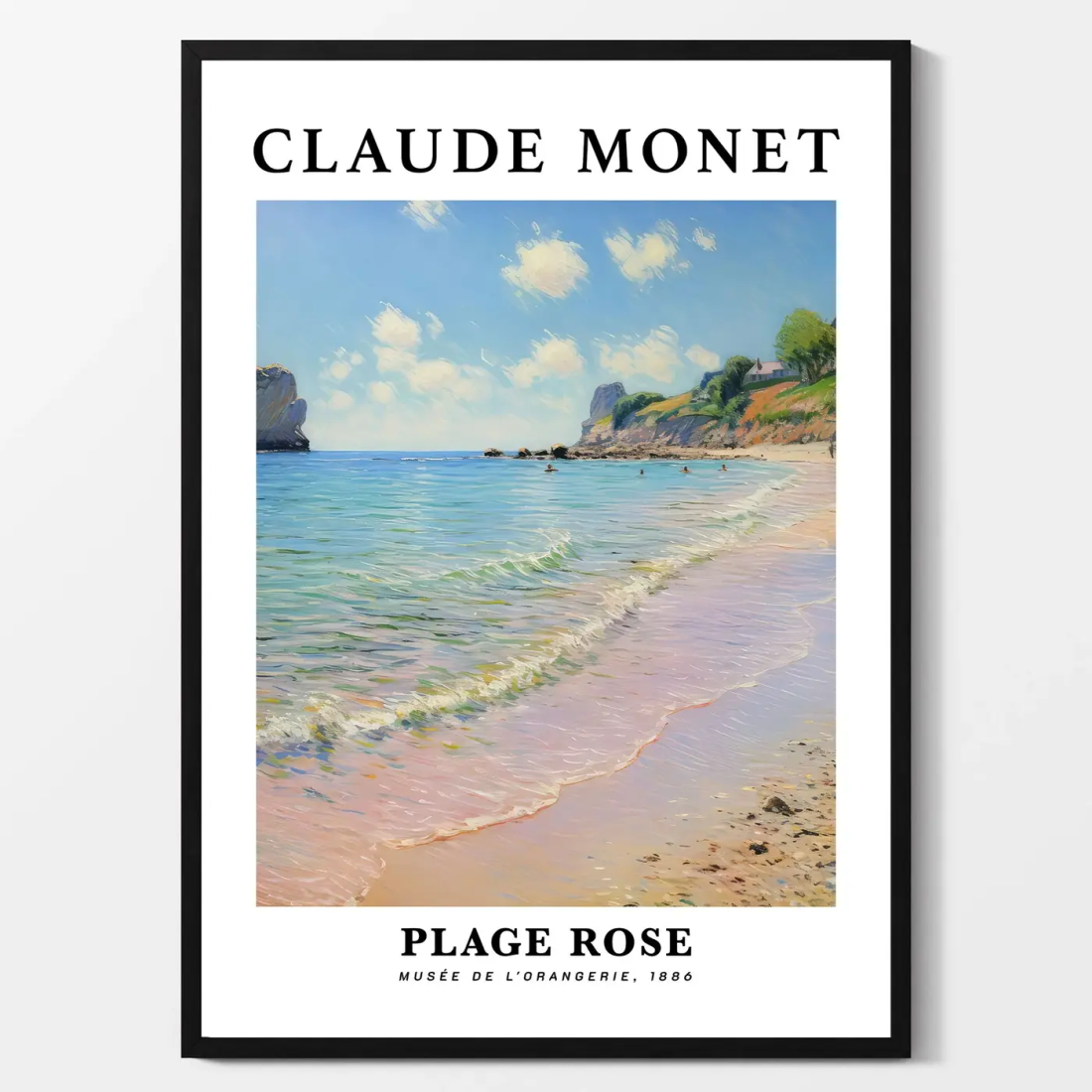

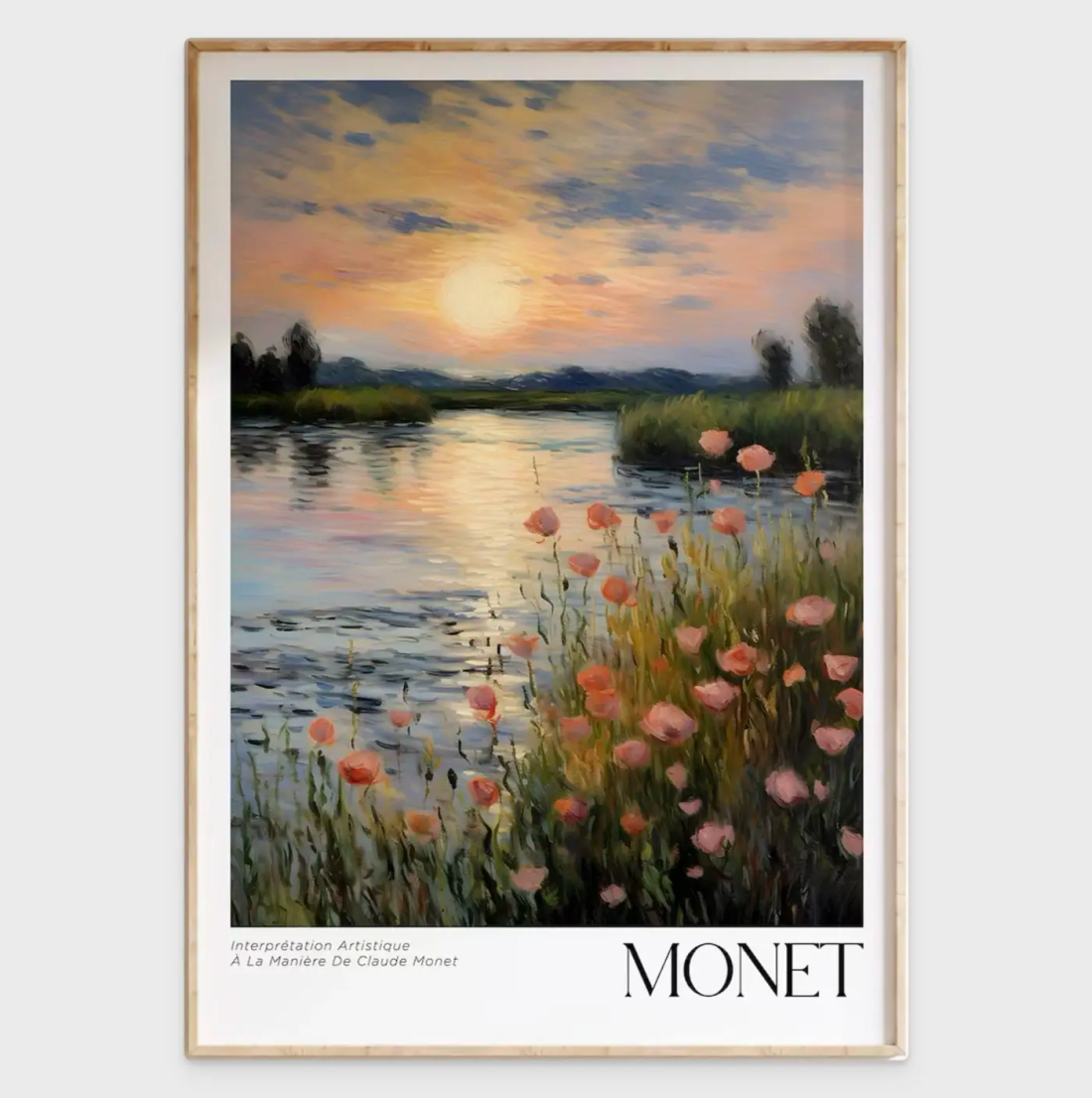

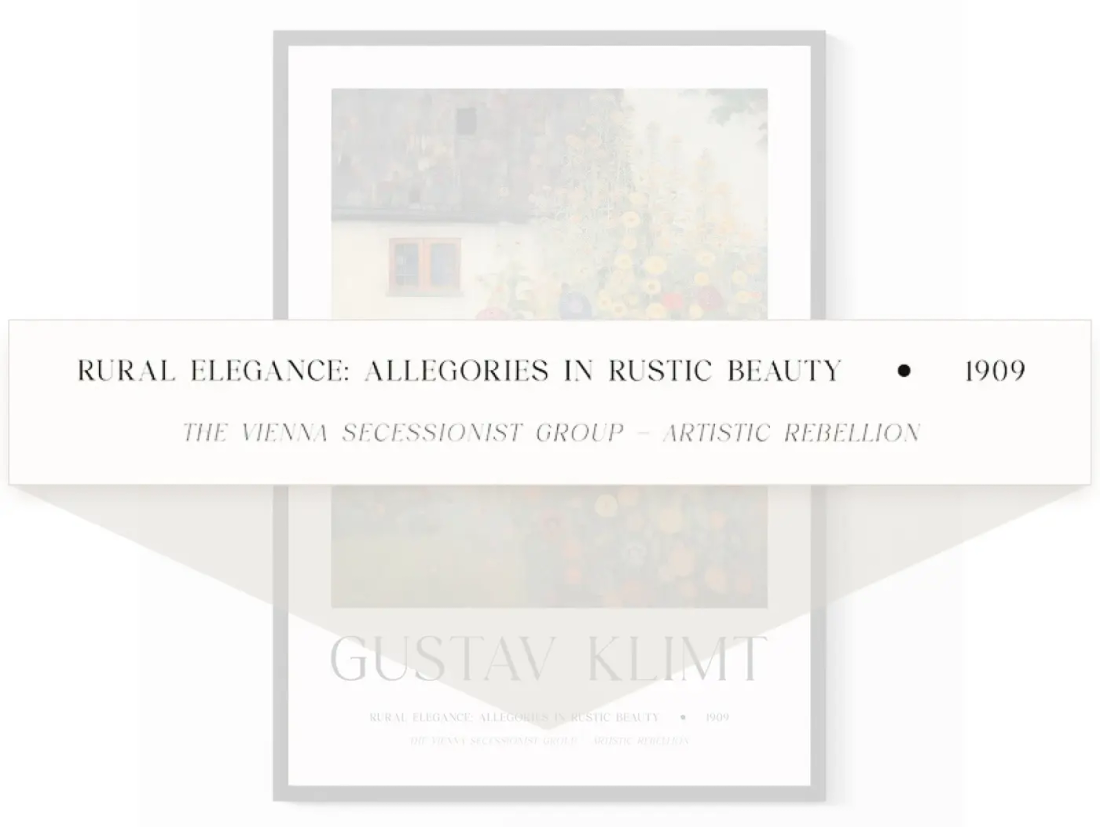

To confound matters, the Etsy stores selling these generated images also sell genuine prints by Morris, Monet, Klimt, and Matisse. These sit alongside their modern expansion packs, blending right in. But which are which? You get coerced into playing an art historian forgery spotter.

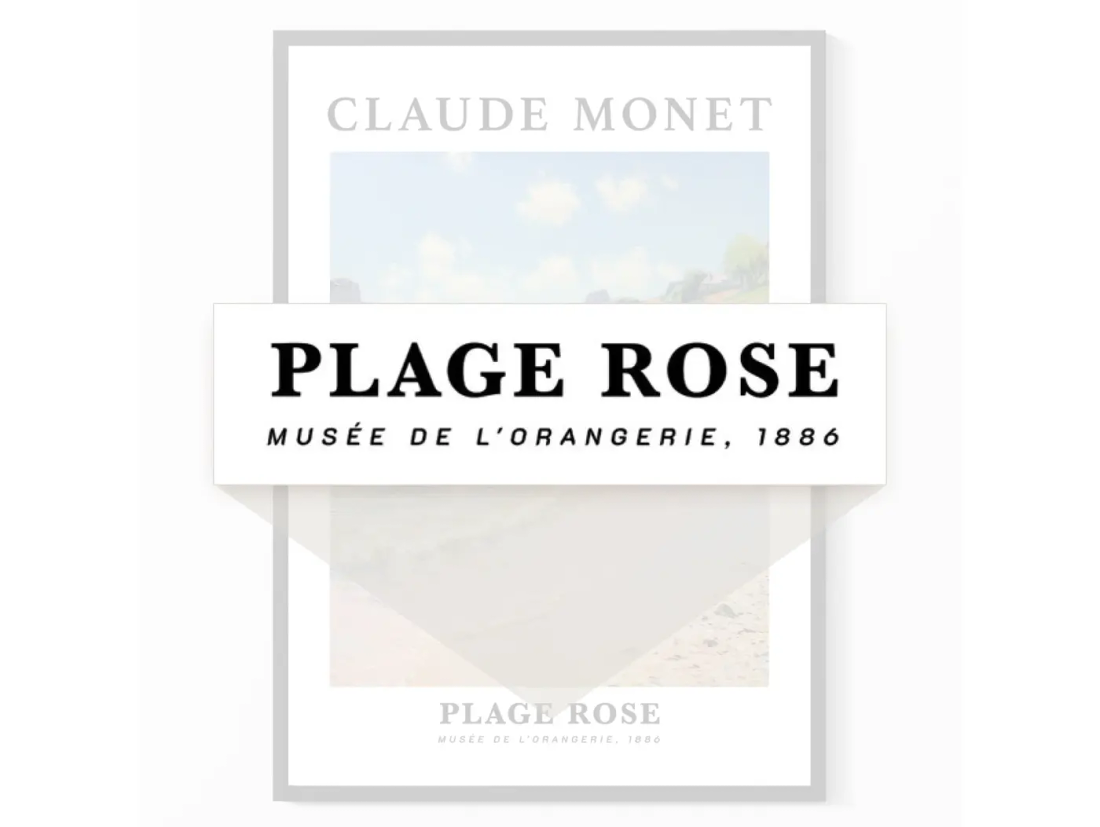

It is hard to overlook the intentional deception at play here. Every print says “William Morris” in the listing title, and has his name in giant block letters on the print itself. The same goes for the Monet, Matisse, and Klimt prints. They often include informational details like artwork titles, exhibit or museum names, cities, and years. What are we to conclude?

What is a label, if not factual information about the thing next to it?

And what is forgery, if not an attempt to pass off an imitation as an authentic original?

You can peruse this evidence and conclude I’m just a gullible idiot, which I’ll accept. A more learned and cultured individual could easily distinguish a real Morris from a Midjourney hoax. Despite earning a snowflakey liberal arts degree, I failed this test. How many others do you think would pass it?

What happens to the next generation of gullible idiots, when they ask their AI assistant to show them “william morris prints,” and those keywords have already been tainted by the sea of Etsy images? What about when more capable models can create even-more-convincing Morris prints, sans their telltale artefacts and slip-ups? When do the generated images become epistemologically indistinguishable from what Morris created?

What happens if we wait years to pass legislation or policy requiring every generated image to bear clear labels and harcoded watermarks? And all the while the model-makers continue to scrape data from the web, train new generations of neural networks on it, and pump the results back out into our information ecosystem. Where shady, short-sighted entrepreneurs and capital-seeking opportunists sit waiting to leverage it in culturally irresponsible ways. Regurgitating history in an endless loop.

What happens if we never pass that legislation?

The snake eats its own tail. And we scramble a whole generation’s understanding of history, tearing at our already threadbare epistemological fabric.