Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Back in April of 20205ya I put up a long twitter thread on the emerging trend of Digital Gardening. It gathered a little buzz, and made clear we’re in a moment where there is something culturally compelling about this concept.

My small collection highlighted a number of sites that are taking a new approach to the way we publish personal knowledge on the web.

They’re not following the conventions of the “personal blog,” as we’ve come to know it. Rather than presenting a set of polished articles, displayed in reverse chronological order, these sites act more like free form, work-in-progress wikis.

A garden is a collection of evolving ideas that aren’t strictly organised by their publication date. They’re inherently exploratory – notes are linked through contextual associations. They aren’t refined or complete - notes are published as half-finished thoughts that will grow and evolve over time. They’re less rigid, less performative, and less perfect than the personal websites we’re used to seeing.

It harkens back to the early days of the web when people had fewer notions of how websites “should be.” It’s an ethos that is both classically old and newly imagined.

A Brief History of Digital Gardens

Let’s go on a short journey to the origin of this word. The notion of a digital garden is not a 20205ya invention. It’s been floating around for over two decades. However, it’s passed through a couple of semantic shifts in that time, meaning different things to different people across the years. As words tend to do.

Tracing back how Neologisms Neologisms

A collection of interesting words that have recently been coined are born helps us understand why anyone needed this word in the first place. Language is always a response to the evolving world around us – we expand it when our current vocabulary fails to capture what we’re observing, or have a particular desire for how we’d like the future to unfold. Naming is a political act as much as a poetic one.

The Early Gardens of Hypertext

Mark Bernstein’s 199827ya essay Hypertext Gardens appears to be the first recorded mention of the term. Mark was part of the early hypertext crowd – the developers figuring out how to arrange and present this new medium.

While the essay is a beautiful ode to free-wheeling internet exploration, it’s less about building personal internet spaces, and more of a manifesto on user experience flows and content organisation.

To put this in its historical context, Mark’s writing was part of a larger conversation happening throughout the nineties around hypertext and its metaphorical framing.

The early web-adopters were caught up in the idea of The Web as a labyrinth-esque community landscape tended by WikiGardeners and WikiGnomes. The caretaking roles given to people who cleaned up broken links, attributions, and awkward white space on shared wiki websites. These creators wanted to enable pick-your-own-path experiences, while also providing enough signposts that people didn’t feel lost in their new, strange medium.

The early web debates around this became known as The Navigation Problem – the issue of how to give web users just enough guidance to freely explore the web, without forcing them into pre-defined browsing experiences. The eternal struggle to find the right balance of chaos and structure.

“Unplanned hypertext sprawl is wilderness: complex and interesting, but uninviting. Interesting things await us in the thickets, but we may be reluctant to plough through the brush, subject to thorns and mosquitoes”

While Mark’s essay was concerned with different problems to the ones we face on the web today, its core ethos feels aligned with our emerging understanding of digital gardening. It captures the desire for exploratory experiences, a welcoming of digital weirdness, and a healthy amount of resistance to top-down structures.

After Mark’s essay the term digital gardening goes quiet for nearly a decade.

Digital Puttering on Twitter

In April of 200718ya when Tweets first started ringing through the internet airwaves, Rory Sutherland (oddly, the vice president of Ogilvy Group) used the term “digital gardening”, but defined it as “faffing about syncing things, defragging - like pruning for young people” For those from outside the Commonwealth, “faffing” means mucking about without a clear direction or useful output

The next dozen mentions on Twitter all followed this sentiment – people were using the term as a way to describe digital maintenance - the act of cleaning up one’s digital space. The focus was on sorting, weeding, pruning, and decluttering, rather than growing and cultivating. People mentioned cleaning out private folders, codebases, and photo albums as the focus of their gardening efforts.

These people were digital puttering more than gardening.

Since none of these folks reference to the earlier nineties notion of digital gardening, or mention issues of hypertext navigation, this use of the word feels like a brief tangent. Given the tiny size of Twitter in the early days, these people probably belonged to the same social flocks and were riffing off one another. It’s not necessarily part of the mainstream narrative we’re tracking, but shows there’s not one strict meaning to the term.

That said, some degree of faffing about, sorting, and pruning are certainly part of the practice of digital gardening. Though best enjoyed in moderation.

Gardens, Streams, and Caufield’s Metaphors

At the 201510ya Digital Learning Research Network, Mike Caufield delivered a keynote on The Garden and the Stream: a Technopastoral . It later becomes a hefty essay that lays the foundations for our current understanding of the term. If anyone should be considered the original source of digital gardening, it’s Caufield. They are the first to lay out this whole idea in poetic, coherent words.

Caufield makes clear digital gardening is not about specific tools – it’s not a Wordpress plugin, Gastby theme, or Jekyll template. It’s a different way of thinking about our online behaviour around information - one that accumulates personal knowledge over time in an explorable space.

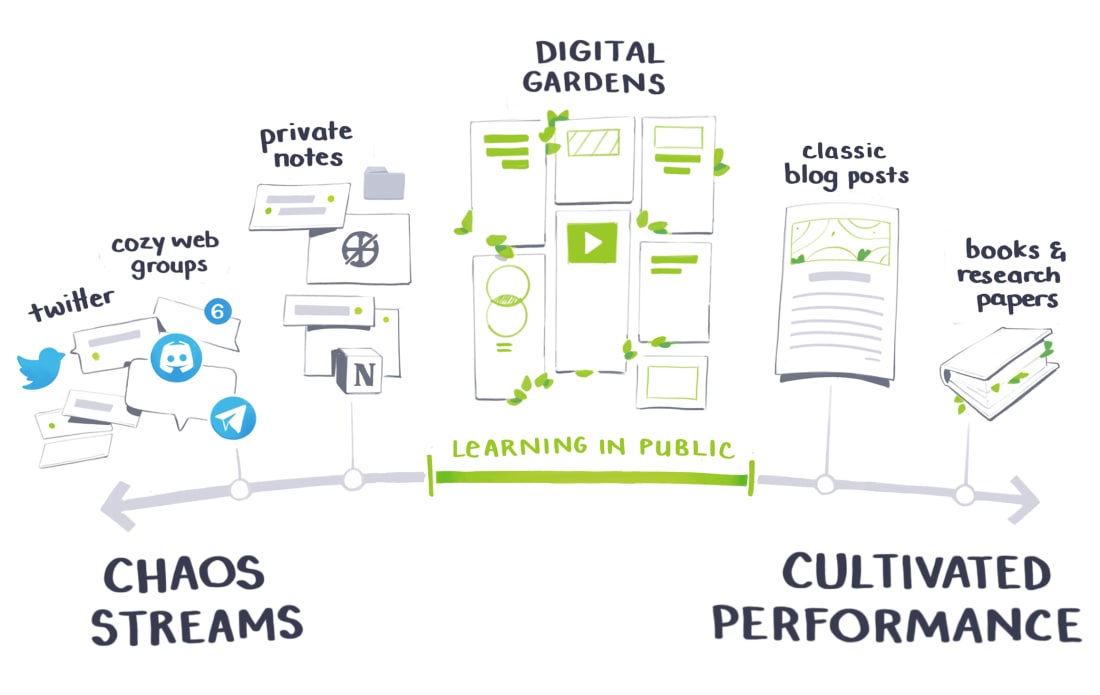

Caufield’s main argument was that we have become swept away by streams – the collapse of information into single-track timelines of events. The conversational feed design of email inboxes, group chats, and InstaTwitBook is fleeting – they’re only concerned with self-assertive immediate thoughts that rush by us in a few moments. While this may sound obvious now, the streamification of everything was still dawning around 201510ya .

This is not inherently bad. Streams have their time and place. Twitter is a force-multiplier for exploratory thoughts and delightful encounters once you fall in with the right crowd and learn to play the game.

But streams only surface the Zeitgeisty ideas of the last 24 hours. They are not designed to accumulate knowledge, connect disparate information, or mature over time. Though the rising popularity of Twitter threading is an impressive attempt to reconfigure a stream environment and make it more garden-esque.

The garden is our counterbalance. Gardens present information in a richly linked landscape that grows slowly over time. Everything is arranged and connected in ways that allow you to explore. Think about the way Wikipedia works when you’re hopping from Bolshevism to Celestial Mechanics to Dunbar’s Number . It’s hyperlinking at it’s best. You get to actively choose which curiosity trail to follow, rather than defaulting to the algorithmically-filtered ephemeral stream. The garden helps us move away from time-bound streams and into contextual knowledge spaces.

“The Garden is the web as topology. The web as space. It’s the integrative web, the iterative web, the web as an arrangement and rearrangement of things to one another.”

Carrying on Caufield

Good ideas take time to germinate, and Caufield’s vision of the personal garden didn’t reach critical mass right off the bat. It lay dormant, waiting for the right time and the right people to find it.

In late 20187ya the corner of Twitter I hang out in began using the term more regularly – folks began passing around Caufield’s original article and experimenting with ways to turn their chronological blogs into exploratory, interlinked gardens.

Tom Critchlow’s 20187ya article Of Digital Streams, Campfires and Gardens was one of the main kick-off points. Tom read Caufield’s essay and began speculating on alternative metaphors to frame the way we consume and produce information. They suggested we add campfires to the idea of streams and gardens – the private Slack groups, casual blog rings, and Cozy Web The Dark Forest and the Cozy Web

An illustrated diagram exposing the inner layers of the dark and cozy web areas where people write in response to one another. While gardens present the ideas of an individual, campfires are conversational spaces to exchange ideas that aren’t yet fully formed.

Tom piece was shortly followed by Joel Hooks’ My blog is a digital garden, not a blog in early 20196ya . Disclaimer that Joel is a mentor, collaborator and friend, so my exposure to the idea comes from his early advocacy and enthusiasm for it. Joel focused on the process of digital gardening, emphasising the slow growth of ideas through writing, rewriting, editing, and revising thoughts in public. Instead of slapping Fully Formed Opinions up on the web and never changing them.

Joel also added Amy Hoy’s How the Blog Broke the Web post to the pile of influential ideas that led to our current gardening infatuation. While not specifically about gardening, Amy’s piece gives us a lot of good historical context. In it, she explores the history of blogs over the last three decades, and pinpoints exactly when we all became fixated on publishing our thoughts in reverse chronological order (spoiler: around 200124ya with the launch of Moveable Type ).

Amy argues that Moveable Type didn’t just launch us into the “Chronological Sort Era”. It also killed the wild, diverse, hodge-podge personalisation of websites that characterised the early web. Instead of hand-coding your own layout and deciding exactly how to arrange the digital furniture, we began to enter the age of standardised layouts. Plug n’ play templates that you drop content into became the norm. It became harder and more technically involved to edit the HTML & CSS yourself.

“Suddenly people weren’t creating homepages or even web pages… they were writing web content in form fields and text areas inside a web page.”

Many people have lamented the web’s slow transition from unique homepages to a bland ocean of generic Wordpress themes. Digital gardening is part of the pushback against the limited range of vanilla web formats and layouts we now for granted.

Over the course 2019 and early 2020, more and more people began riffing on the concept. Shaun Wang compiled the Digital Gardening Terms of Service . Anne-Laure Le Cunff published a popular guide to setting up No-code Digital Gardens . The IndieWeb community hosted a pop-up session to discuss the history of commonplace books, personal wikis, and memory palaces.

By late 2020 this whole concept had attracted enough attention for the MIT Tech Review to write a short piece on it. Perhaps this is the watershed moment when a Twitter buzzword has “made it.”

Digital Gardening’s Fertile Soil

What made our current historical moment the right time for digital gardening to take off?

The timing coincided with a few complimentary ideas and communities rallying around personal knowledge systems, note-taking practices, and reimagining tools for blogging. The scene was ripe for new ideas around curating and sharing personal knowledge online.

Many of the people who jumped on the early digital gardening bandwagon were part of communities like…

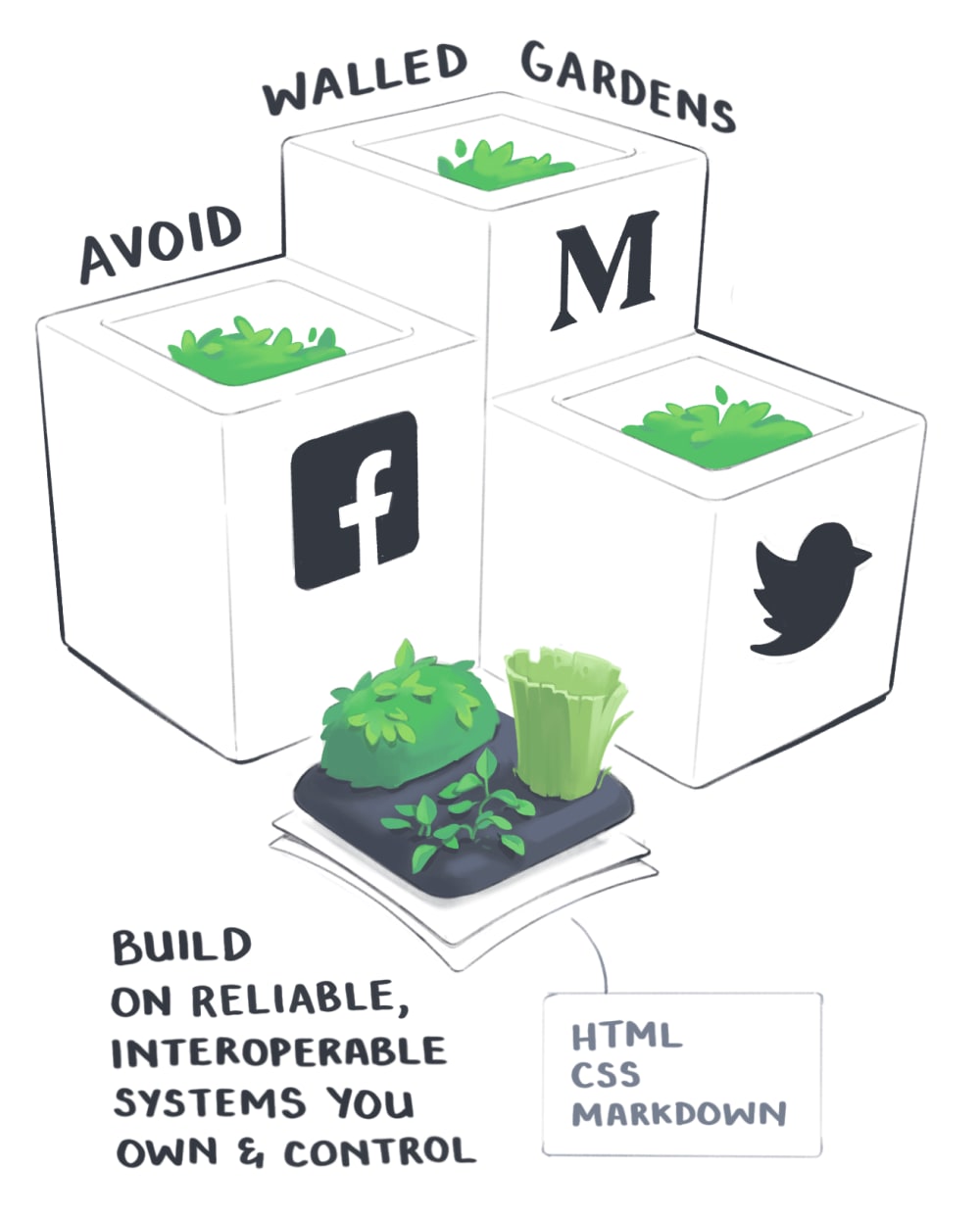

- The IndieWeb collective – a group that has been championing independent web spaces outside the walled gardens of Instatwitbook for nearly a decade.

- Users of the note-taking app Roam Research – Roam pioneered new ways of interlinking content and strongly appeals to people trying to build sprawling knowledge graphs.

- Followers of Tiago Forte’s Building a Second Brain course which popularised the idea of actively curating personal knowledge.

- People rallying around the Learn in Public ethos that encourages continuously creating ‘learning exhaust’ in the form of notes and summaries.

Developer-led Gardening

Many of these early adopters were people who understood how to build websites – either professional developers or enthusiastic hobbyists. Any kind of novel experimentation with the web requires knowing a non-trivial amount of HTML, CSS, and JS. Not to mention all the surrounding infrastructure required actually to get a site live. Developers took to the idea because they already had the technical ability to jump in play around with what garden-esque websites might look like.

The current state of web development helped here too. While it feels like we’ve been in a slow descent into a horrifyingly complex and bloated web development process, a number of recent tools have made it easier to get a fully customised website up and running. Services like Netlify and Vercel have taken the pain out of deployment. Static site generators like Jekyll , Gatsby , 11ty and Next make it easier to build sophisticated websites that auto-generate pages, and take care of grunt work like optimising load time, images, and SEO. Plenty of people will disagree that this explosion of JavaScript-stuffed rubbish is a net gain for the web. We all lament the loss of being able to upload pure HTML and CSS files via FTP. But those days are gone, and the only thing we can do now is slowly untangle our JavaScript spaghetti and package it up into more accessible build tools. These services are trying to find a happy middle ground between tediously hand-coding solutions, and being trapped in the restrictions of Wordpress or Squarespace.

While developers were the first on the scene, plenty of writers, researchers, and note-taking enthusiasts have been drawn to the idea of digital gardening.

To help folks without programming skills join in, there’s been a surge in templates and platforms that allow people to build their own digital gardens without touching a ton of code. I’ve written an entire guide to Digital Gardening for Non-Technical Folks Digital Gardening for Non-Technical Folks

How to build a digital garden without touching code if you fall into that category.

Tools like Obsidian , TiddlyWiki , and Notion are all great options. Many of them offer fancy features like nested folders, Bi-Directional Links A Short History of Bi-Directional Links

Seventy years ago we dreamed up links that would allow us to create two-way, contextual conversations. Why don't we use them on the web? , footnotes, and visual graphs.

However, many of these no-code tools still feel like cookie-cutter solutions. Rather than allowing people to design the information architecture and spatial layouts of their gardens, they inevitably force people into pre-made arrangements. This doesn’t meant they don’t “count,” as “real” gardens, but simply that they limit their gardeners to some extent. You can’t design different types of links, novel features, experimental layouts, or custom architecture. They’re pre-fab houses instead of raw building materials.

The Six Patterns of Gardening

In all the recent gardening flurry, we’ve run into the inevitable confusion around how to define the term.

There are contested ideas about what qualifies as a garden, what the core ethos should focus on, and whether it’s worthy of a new label at all. What exactly makes a website a digital garden as opposed to just another blog?

After reading all the existing takes on the term, observing a wide variety of gardens, and collecting some of the best examples , I’ve identified a few key qualities they all share.

There are a few guiding principles, design patterns and structures people are rallying around. This amounts to a kind of digital gardening Pattern Language Pattern Languages in Programming and Interface Design

Notes on pattern languages and Christopher Alexander's legacy on software programming .

1. Topography over Timelines

Gardens are organised around contextual relationships and associative links; the concepts and themes within each note determine how it’s connected to others.

This runs counter to the time-based structure of traditional blogs: posts presented in reverse chronological order based on publication date.

Gardens don’t consider publication dates the most important detail of a piece of writing. Dates might be included on posts, but they aren’t the structural basis of how you navigate around the garden. Posts are connected to other by posts through related themes, topics, and shared context.

One of the best ways to do this is through Bi-Directional Links A Short History of Bi-Directional Links

Seventy years ago we dreamed up links that would allow us to create two-way, contextual conversations. Why don't we use them on the web? – links that make both the destination page and the source page visible to the reader. This makes it easy to move between related content.

Because garden notes are densely linked, a garden explorer can enter at any location and follow any trail they link through the content, rather than being dumped into a “most recent” feed.

Dense links are essential, but gardeners often layer on other ways of exploring their knowledge base. They might have thematic piles , nested folders , tags and filtering functionality, advanced search bars , visual node graphs , or central indexes listing notable and popular content.

Many entry points but no prescribed pathways.

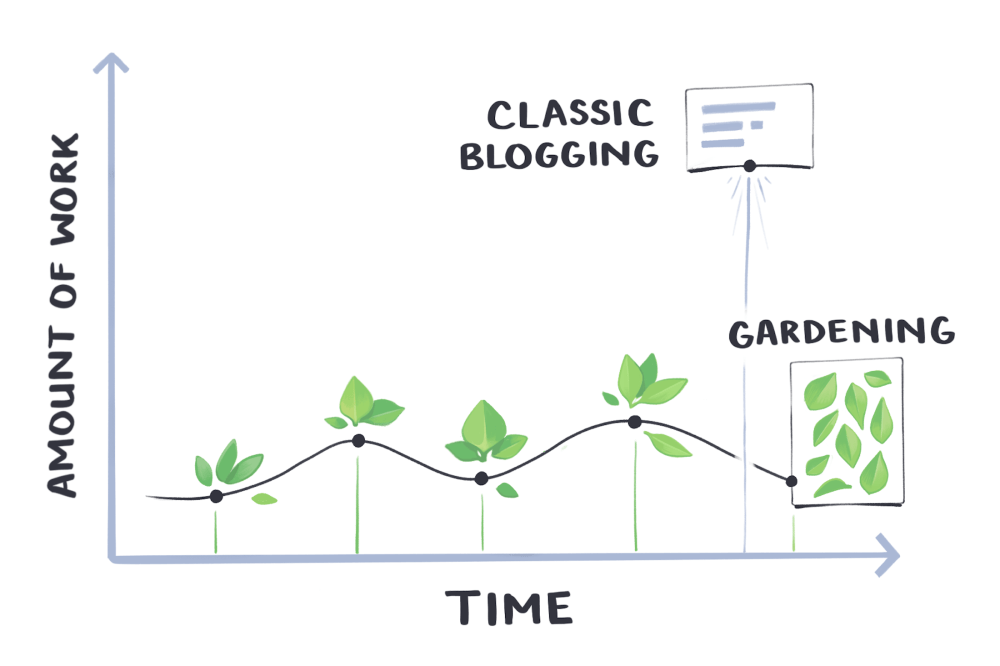

2. Continuous Growth

Gardens are never finished, they’re constantly growing, evolving, and changing. Just like a real soil, carrot, and cabbage garden.

The isn’t how we usually think about writing on the web. Over the last decade, we’ve moved away from casual live journal entries and formalised our writing into articles and essays. These are carefully crafted, edited, revised, and published with a timestamp. When it’s done, it’s done. We act like tiny magazines, sending our writing off to the printer.

This is odd considering editability is one of the main selling points of the web. Gardens lean into this – there is no “final version” on a garden. What you publish is always open to revision and expansion. Or more likely, contraction and clarification

Gardens are designed to evolve alongside your thoughts. When you first have an idea, it’s fuzzy and unrefined. You might notice a pattern in your corner of the world, but need to collect evidence, consider counter-arguments, spot similar trends, and research who else has thunk such thoughts before you. In short, you need to do your homework and critically think about it over time.

In performance-blog-land you do that thinking and researching privately, then shove it out at the final moment. A grand flourish that hides the process.

In garden-land, that process of researching and refining happens on the open internet. You post ideas while they’re still “seedlings,” and tend them regularly until they’re fully grown, respectable opinions.

This has a number of benefits:

- You’re freed from the pressure to get everything right immediately. You can test ideas, get feedback, and revise your opinions like a good internet citizen.

- It’s low friction. Gardening your thoughts becomes a daily ritual that only takes a small amount of effort. Over time, big things grow.

- It gives readers an insight into your writing and thinking process. They come to realise you are not a magical idea machine banging out perfectly formed thoughts, but instead an equally mediocre human doing The Work of trying to understand the world and make sense of it alongside you.

This all comes with an important caveat; gardens make their imperfection known to readers. Which brings us to the next pattern…

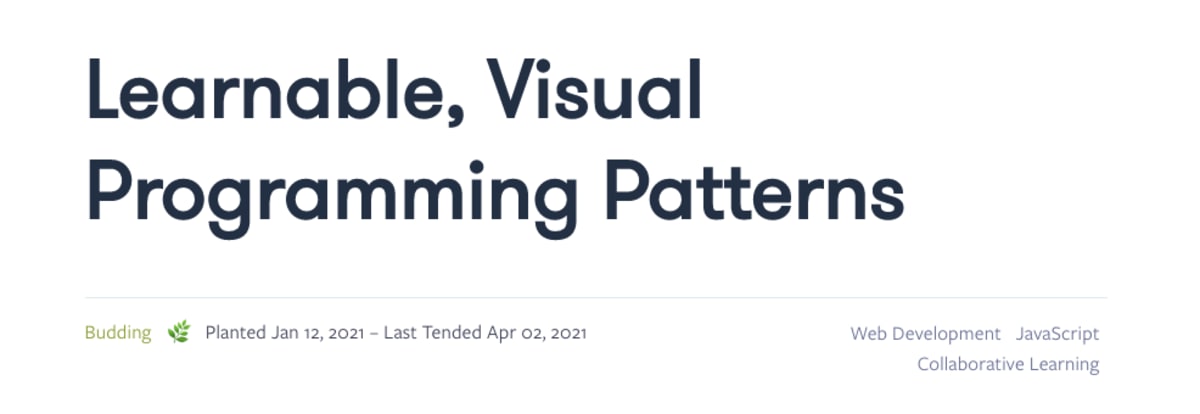

3. Imperfection & Learning in Public

Gardens are imperfect by design. They don’t hide their rough edges or claim to be a permanent source of truth.

Putting anything imperfect and half-written on an “official website” may feel strange. We seem to reserve all our imperfect declarations and poorly-worded announcements for platforms that other people own and control. We have all been trained to behave like tiny, performative corporations when it comes to presenting ourselves in digital space. Blogging evolved in the Premium Mediocre culture of Millenialism as a way to Promote Your Personal Brand™ and market your SEO-optimized Content.

Weird, quirky personal blogs of the early 2000’s turned into cleanly crafted brands with publishing strategies and media campaigns. Everyone now has a modern minimalist logo and an LLC.

Digital gardening is the Domestic Cozy response to the professional personal blog; it’s both intimate and public, weird and welcoming. It’s less performative than a blog, but more intentional and thoughtful than a Twitter feed. It wants to build personal knowledge over time, rather than engage in banter and quippy conversations.

Think of it as a spectrum. Things we dump into private WhatsApp group chats, DMs, and cavalier Tweet threads are part of our chaos streams - a continuous flow of high noise / low signal ideas. On the other end we have highly performative and cultivated artefacts like published books that you prune and tend for years.

Gardening sits in the middle. It’s the perfect balance of chaos and cultivation.

This ethos of imperfection opens up a world of possibility that performative blogging shut down. First, it enables you to Learn in Public ; the practice of sharing what you learn as you’re learning it, not a decade later once you’re an “expert.” A label you may never officially earn unless you’re in a highly structured and bureaucratised industry that loves explicit hierarchy rankings. The rest of us are left to deal with perpetual imposter syndrome.

This freedom of course comes with great responsibility. Publishing imperfect and early ideas requires that we make the status of our notes clear to readers. You should include some indicator of how “done” they are, and how much effort you’ve invested in them.

This could be with a simple categorisation system. I personally use an overly horticultural metaphor:

- 🌱 Seedlings for very rough and early ideas

- 🌿 Budding for work I’ve cleaned up and clarified

- 🌳 Evergreen for work that is reasonably complete (though I still tend these over time).

I also include the dates I planted and last tended a post so people get a sense of how long I’ve been growing it.

Other gardeners include an epistemic status on their posts – a short statement that makes clear how they know what they know, and how much time they’ve invested in researching it.

Gwern.net was one of the earliest and most consistent gardeners to offer meta-reflections on their work. Each entry comes with:

- topic tags

- start and end date

- a stage tag: draft, in progress, or finished

- a certainty tag: impossible, unlikely, certain, etc.

- 1-10 importance tag

These are all explained in their website guide , which is worth reading if you’re designing your own epistemological system.

Devon Zuegal is another notable gardener who has epistemic status and epistemic effort on their posts, indicating both their certainty level about the material, and how much effort went into making it. They also make a strong case for lazy epistemic statuses as a feature, not a bug.

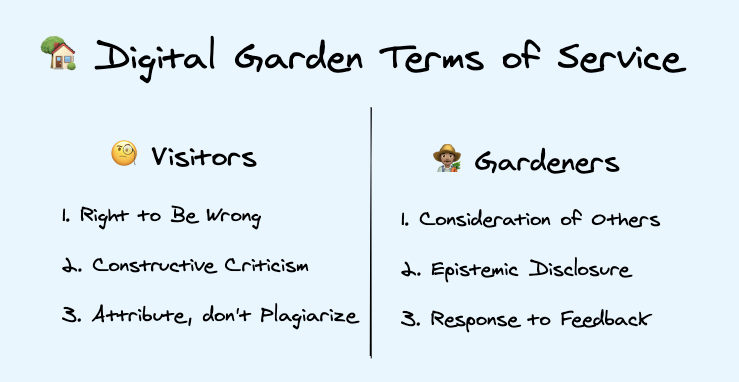

In a similar vein, Shawn Wang has written the Digital Gardening Terms of Service which I adore and ascribe to. They ask the reader to allow the writer to be wrong, offer constructive criticism, and attribute their work. They ask gardeners to be considerate of others (don’t share private information or name and shame), offer epistemic disclosure, and respond to feedback.

All of these design patterns feed our growing desire for transparency, meta information, and breadcrumbs back to the source of ideas.

4. Playful, Personal, and Experimental

Gardens are non-homogenous by nature. You can plant the same seeds as your neighbour, but you’ll always end up with a different arrangement of plants.

Digital gardens should be just as unique and particular as their vegetative counterparts. The point of a garden is that it’s a personal playspace. You organise the garden around the ideas and mediums that match your way of thinking, rather than off someone else’s standardised template.

Ideally, this involves experimenting with the native languages of the web – HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. They’re the most flexible and robust tools we have for building interconnected knowledge online. Gardens are a chance to question the established norms of a ‘personal website’, and make space for weirder, wilder experiments.

That said, I should acknowledge that jumping into full-on web development is simply beyond the abilities and interests of many people. There is still room for personalisation and play if you’re using a pre-made template or service – it’ll just be within the constraints of that system.

One goal of these hyper-personalised gardens is deep contextualisation. The overwhelming lesson of the Web 2.0 social media age is that dumping millions of people together into decontextualised social spaces is a shit show. Devoid of any established social norms and abstracted from our specific cultural identities, we end up in awkward, aggravating exchanges with people who are socially incoherent to us. We know nothing of their lives, backgrounds, or belief systems, and have to assume the worst. Twitter only offers us a 240 character bio. Facebook pre-selects the categories it deems important about you – relationship status, gender, hometown.

Gardens offer us the ability to present ourselves in forms that aren’t cookie cutter profiles. They’re the higher-fidelity version, complete with quirks, contradictions, and complexity.

5. Intercropping & Content Diversity

Gardens are not just a collection of interlinked words. While linear writing is an incredible medium that has served us well for a little over 5000 years, it is daft to pretend working in a single medium is a sufficient way to explore complex ideas.

It is also absurd to ignore the fact we’re living in an audio-visual cornucopia that the web makes possible. Podcasts, videos, diagrams, illustrations, interactive web animations, academic papers, tweets, rough sketches, and code snippets should all live and grow in the garden.

Historically, monocropping has been the quickest route to starvation, pests, and famine. Don’t be a lumper potato farmer while everyone else is sustainably intercropping.

6. Independent Ownership

Gardening is about claiming a small patch of the web for yourself, one you fully own and control.

This patch should not live on the servers of Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram (aka. also Facebook), or Medium. None of these platforms are designed to help you slowly build and weave personal knowledge. Most of them actively fight against it.

If any of those services go under, your writing and creations sink with it (crazier things have happened in the span of humanity). None of them have an easy export button. And they certainly won’t hand you your data in a transferable format.

Independently owning your garden helps you plan for long-term change. You should think about how you want your space to grow over the next few decades, not just the next few months.

If you give it a bit of forethought, you can build your garden in a way that makes it easy to transfer and adapt. Platforms and technologies will inevitably change. Using old-school, reliable, and widely used web native formats like HTML/CSS is a safe bet. Backing up your notes as flat markdown files won’t hurt either.

Keeping your garden on the open web also sets you up to take part in the future of gardening. At the moment our gardens are rather solo affairs. We haven’t figure out how to make them multi-player. But there’s an enthusiastic community of developers and designers trying to fix that. It’s hard to say what kind of libraries, frameworks, and design patterns might emerge out of that effort, but it certainly isn’t going to happen behind a Medium paywall.

This is all my take on gardening, but knowledge and neologisms always live within communities. No one owns The Official Definition of digital gardening. Numerous people have contributed to the growing conversation and you should read their thoughts as well.